2023/2024 FR/EU reviews:

Falstaff at the Opéra Bastille (September 10, 2024)

Il barbiere di Siviglia in Pesaro (August 19, 2024)

Bianca e Falliero in Pesaro (August 18, 2024)

Ermione in Pesaro (August 17, 2024)

L'equivoco stravagante in Pesaro (August 16, 2024)

The Gambler in Salzburg (August 13, 2024)

The Idiot in Salzburg (August 12, 2024, 2024)

Tristan und Isolde in Bayreuth (August 9, 2024, 2024)

Der Fliegende Holländer in Bayreuth (August 8, 2024)

Il ritorno d'Ulisse in Aix (August 19, 2024)

Kafka-Fragmente in Aix (July 12, 2024)

Eight Songs for a Mad King in Aix (July 12, 2024)

Samson in Aix (July 15, 2024)

Madama Butterfly in Aix (July 10, 2024)

Iphigénie en Tauride in Aix (July 8, 2024, 2024)

Iphigénie en Aulide in Aix (July 8, 2024, 2024)

L'Orfeo in Cremona (June 21, 2024)

La Vestale in Paris (June 19, 2024)

The Extirminating Angel in Paris (March 17, 2024)

Simon Boccanegrar in Paris (March 19, 2024)

Pique Damein Lyon (March 16, 2024)

La fanciulla del Westin Lyon (March 15, 2024)

La traviata in Marseille (February 15, 2024)

Adriana Lecouvreur at the Opéra Bastille (February 7, 2024)

Giulio Cesare at the Palais Garnier (February 8, 2024)

Beatrice di Tenda at Opéra Bastille (February 9, 2024)

Die Frau ohne Schatten in Toulouse (January 31, 2024)

Falstaff at the Opéra Bastille

It was magic from the start, Verdi’s in medias res chords exploded and tumbled, Danish conductor Michael Schønwandt established the solid, brisk beat, brilliantly illuminating Verdi’s vast musical complexities to their final cadence.

Verdi’s unparalleled masterpiece shone in its comic majesty, integrated into French stage director Dominique Pitoiset’s once progressive, now venerable 1999 production. Pitoiset had staged a series of Shakespeare plays for progressive theaters in Milan and Torino that caught the eye of Hugues Gall, the then (1995-2004) general director of the Opéra de Paris. Paris Opera had already celebrated the famed Italian theater director Giorgio Strehler, thus it was an evident choice to tap a director imbued in pristine progressive Italian theater to stage this prestigious Italian Shakespeare knock-off.

Pitoiset set the opera in front of a giant, late Victorian, industrial façade fronting the Quickley Steam Laundry, together with the ubiquitous British pub, an entry point for visits to Windsor Park and its famed tree, and an automobile repair garage which contained a classic British roadster. To change the scenes the huge façade magically traversed the stage — a vista! — moving on and off the stage to reveal its various components in different configurations. Wittily, the huge wall arrived finally at the black oak, its final destination, and stopped, at which point the car, evidently finally repaired, then drove off the stage.

All this was possible because the then new Opéra Bastille boasted massive wing space.

Andrii Kymach as Ford, Ambrogio Maestri as Falstaff

The massive wall made a parallel, always lively, always witty world to what Verdi’s famed librettist, Arrigo Boito made of Shakespeare’s tale. Director Pitoiset respected the Italian makeover to the letter. The play itself was downstage, its characters in high relief, its towering Falstaff was portly indeed. Falstaff’s tormentors, Bardolfo and Pistola effected slick Goldoni physical theater à la Strehler, complementing the commedia dell'arte, clownlike wigs of Falstaff and Pistola. The plotting women were carefully grouped together to deliver their tricky music in highly theatrical poise. Nanetta and Fenton flitted airily across the stage. And finally Ford was left quite alone on the darkened stage to vent his cuckolded rage.

The action moved always in slickly theatrical terms, all ten principals in swift, highly directed, chaotic motion that was the second act finale, arriving finally in a line across the front of the stage to summon the final musical confusion, at which point Falstaff was dumped into the steaming river.

The Opéra de Paris enlisted a splendid cast. That they were of big, beautiful voice was a bonus, given the amplitude of the Opéra Bastille, its mighty orchestra revved up to deliver the Verdi masterpiece with maximum energy. Italian baritone Ambrogio Maestri as the Falstaff. It is his signature role, first performed at La Scala in 2001, performed as well in the 2013 incarnation of the Pitoiset Falstaff at the Bastille. Mr. Maestri earned an impromptu ovation for his roar of indignation at the very idea of “honor,” but later found a great beauty of tone and phrasing in his humiliated “Mondo ladro, mondo rubaldo, reo mondo,” achieving finally an actual nobility of tone for a capitulatory “Tutto nel mondo è burla.”

Ford was sung by Ukrainian baritone Andrii Kymach. Of sharply focused, golden hued voice Mr. Kymach has an intense, dark-eyed presence. He tore up the stage with his “È sogno o realta … due rami enormi,” easily slipping into Ford’s blinding rage, then succumbing into a pure opera buffa victim of his own cunning as the pater familias.

Peruvian tenor Iván Ayón Rivas lent very beautiful, ample lyric tenor voice to Fenton, easily finding the exquisite beauty Verdi imbued into his Act III “Dal labbro il canto estasiato vola.” Nannetta was sung by Italian soprano Federica Guida in ample, Italianate lyric tone that added considerable musical and dramatic heft to her fairy queen masquerade “Sul fil d’un soffio etesio ”

The heavier voices of Mr. Rivas and Mme. Guida as they played out their love story in this performance added enormous emotional warmth and dramaturgical reward, equalling in impact the comic comeuppances of Falstaff and Ford, and the warmth of Falstaff’s acceptance of the absurdity of his existence.

Conductor Schønwandt underscored the absolute absurdity of the opera by giving us at last a carefully paced fugue, each of its voices entering in absolute clarity, emerging finally, somehow, in Verdi’s maelstrom of magnificent musical turmoil.

Olivia Boen as Alice Ford, Federica Guida as Nannetta, Marie-Nicole Lemieux as Mistress Quickly, Marie-Andrée Bouchard-Lesieu as Meg Page

Alice Ford was sung by American soprano Olivia Boen with great warmth of voice, and sense of comic timing. Mistress Quickly was sung by Canadian contralto Marie-Nicole Lemieux in a performance that was fully, and beautifully sung with but little trace of the caricature that is usual for this sometimes character role. Mrs. Meg Page was sung by French mezzo-soprano Marie-Andrée Bouchard-Lesieur, Meg’s usual aplomb pointedly exaggerated.

Bardolfo was sung by agile Australian character tenor Nicholas Jones who tumbled gracefully in a nod to Goldoni, Pistola, the driver of the classic roadster, was sung by Italian bass Alessio Cacciamani in booming voice (lead photo with Falstaff). Dr. Cajus was rendered by Italian character tenor Gregory Bonfatti as total caricature, betraying the purer dramaturgy of the production.

Scenery was designed by Alexandre Beliaev, costumes by Elena Rivkina. The original lighting was designed by Philippe Albaric, adapted by Christophe Pitoiset both in 2017 and just now. The chorus and orchestra of the Opéra national de Paris, Opéra Bastille, Paris, France, September 10, 2024.

All photos copyright Vincent Pontet, courtesy of the Opéra de Paris

Il barbiere di Siviglia in Pesaro

The city of Pesaro is the 2024 Capitale Italiana della Cultura, adding luster to its 2017 Unesco designation as a Città Creativa. All this calls for celebration, and that was the addition of a fourth production to the festival’s usual three — and no opera is more celebratory than Il barbiere!

It was the reprise of Pier Luigi Pizzi’s splendid 2018 production, a mise en scène that celebrated Rossini’s most famous opera with great elegance and sophistication. His singers dwelt on Rossini’s finely wrought vocal lines, gracefully accomplishing their musical elaboration. The comic situations were subtly conceived and carefully executed. It was an exquisite production.

Pier Luigi Pizzi, now age 94, originally studied architecture. He began his theatrical life as a set and costume designer, working with the storied Italian theater directors Giorgio Strehler and Luca Ronconi, the first directors to impose a strong, purely theatrical perspective onto their stagings of both theater and opera. Both directors worked in a highly distilled style, the theatrical structure of the drama emerging in absolute clarity, first and foremost.

Pizzi was imbued with this esthetic. Later, at age 47, he took on the staging of operas as well designing. In such esthetic was this 2018 production. [See my review in Archives.]

No longer a tightly controlled, directorial statement, this 2024 reprise became a romp for the singers, and a vanity piece for conductor Lorenzo Passerini who stood cockily before the Orchestra Sinfonica Gioachino Rossini, applauding the singers’ showpieces (lightly tapping his baton onto his opened hand), when not dancing grandly in front of the orchestra, urging it to ever greater fortes.

The singers gave their all, and then more. Fiorello, sung by Italian baritone William Corrò, sang so softly in his “Piano, pianissimo” entrance with Lindoro’s accompanists that he was inaudible, though later we learn he has a big, booming voice. Figaro, sung by Polish baritone Andrzfej Filonczyk (lead photo, right), strutted his beefcake catwalk tour so cockily that one almost overlooked that he was bellowing. Lindoro, sung by American tenor Jack Swanson (lead photo, left), knew he had big competition for being the fastest and loudest, thus his fioratura in the Figaro/Lindoro “All’idea di qual metal” was compromised, though he accomplished his final “Cessa di piu resistere” with requisite virtuosity.

Left to right, Michele Pertusi as Bartolo, Carlo Lepore as Bartolo, Andrzfej Filonczyk as Figaro, Jack Swanson as Lindoro, Maria Kataeva as Rosina, Patrizia Biccirè as Berta

Rossina, sung by Russian mezzo-soprano Maria Kataeva, was a very presentational creature, making one think of Carmen. A fine moment in the Pizzi mise en scène is the storm scene, imagined by Pizzi to be Rosina imagining that Lindoro has betrayed her trust. Such vulnerability proved well beyond Mlle. Kataeva’s emotional range.

Bartolo was sung by Italian buffo Carlo Lepore, veteran of many Pesaro productions, here up against the greatly overblown Basilio of Italian buffo Michele Pertusi.

All the artists of the production have established careers on major stages. I am bewildered by these performances, evidently sanctioned by Pizzi who oversaw the production with his longtime associate Massimo Gasparon.

Please see my review of yet another Pesaro Barbiere, this one from 2014. Though far from finding the theatrical perfection of Pizzi’s 2018 Barber, it was of great interest, and wonderful fun, famed Figaro Florian Sempey in his role debut!

Vitrifrigo Arena, Pesaro, Italy, August 19, 2024. All photos copyright Amati Bacciardi, courtesy of the Rossini Opera Festival.

Bianca e Falliero in Pesaro

Expectations were high in Pesaro just now, not for the new production of Bianca e Falliero by French stage director Jean-Louis Grinda (expectations were low), but of the Rossini Opera Festival’s return to the Parafestival, a sort of community space that closed for an upgrade in 2006. Finally re-opened 18 years later, the theater (serving as well as a basketball court) is now named the Auditorium Scavolini.

While the stage seems kind to singers, the pit offers an unflattering orchestral sound, huge fortes with chorus overburden the hall’s acoustic. The seating is on closely spaced, tiny chairs on dangerous gradations, many seats placed behind glass walls! Public amenities (restrooms) are not even minimal. It is a sad example of adaptive reuse architecture, its only advantage is its proximity to Pesaro’s hotels.

While the 1819 premiere of Rossini’s Bianca e Falliero occurred during the raging Milanese conflict of Romanticism with Classicism, we, as Rossinian classicists, are in Pesaro to celebrate florid singing and old fashioned dramaturgy — love vs. duty! The Rossini Festival’s artistic director Juan Diego Flóres awarded us a splendid cast, but a production that ignored the challenges of translating classical tensions into a current theatrical language.

Bianca e Falliero is a quartet of principal singers — Bianca a soprano (lead photo), Falliero a travesty mezzo soprano (lead photo), Bianca’s father a tenor, her arranged fiancé a bass — who all come together in the grand quartet that precedes Bianca’s triumphant, brilliant final aria “Teco io resto: in te rispetto,” reconciling, finally, her father with her lover.

La Scala librettist Felice Romani concocted a melodrama that laboriously charts the betrothal of Bianca to Capellio, a marriage that will financially save Bianca’s father Contareno, though Bianca’s triumphant warrior lover Falliero had just returned to Venice. Handily Venice had just passed a law condemning to death anyone who consorts with the enemy. Unfortunately the only escape possible from Falliero’s secret meeting with Bianca was through the Spanish ambassador’s house (the Spanish Hapsburgs controlled much of northern Italy in the 17th and 18th centuries).

Bianca was sung by Australian soprano Jessica Pratt, a singer of beautiful voice and impeccable technique, in perfectly matched, pure vocal colors to the Falliero, sung by Japanese mezzo soprano Aya Wakizono who showed magnificently in her Act II showpiece “Tu non sai qual colpo atroce” (Falliero believes that Bianca has actually married Capellio). This care in casting paid off handsomely in the three duets Rossini gifted these matched female voices, the Act I “Sappi che un Dio crudele” melding the voices in exquisite pianos.

Giorgi Manoshvili as Capellio, Aya Wakizono as Falliero

The situation resolved itself when Capellio, the arranged fiancé, was moved by Bianca’s testimony to the Venetian senate. He suddenly withdrew all his claims on Bianca and manipulated circumstances to save Falliero’s life. The role was sung by young Georgian bass Georgi Manoshvili in very beautiful, sympathetic, pure bass tones, succumbing from time to time to Capellio’s compulsion to indulge in well executed fioratura.

Bianca’s father Contareno was sung by Russian tenor Dmitry Korchak who raged floridly throughout the opera at his daughter reluctance to heed her filial duty and Falliero’s audacity to love Bianca, upsetting Contareno’s plans. Roles facilitating the action, usually in dry (fortepiano only) recitative, were Priuli sung by Nicolò Donini, Costanza sung by Carmen Buendía, Usciere sung by Claudio Zazzaro and the Cancelliere sung by D’Angelo Díaz.

Stage director Jean-Louis Grinda attempted to involve us in his production by showing us actual, tearjerking footage of Italian suffering during WWII during the opening chorus urging Venice to remain strong in the face of the Spanish threat.

The setting, designed by Rudy Sabounghi, was a wooden box in rich browns often bathed in golden light. The box broke into units that were configured in ever changing ways, pushed by stagehands in formal attire, sometimes revealing a backdrop of a realistic looking lagoon lighted by the moon. Director Grinda effected perfunctory stage movement, often clumsy, for both chorus and principals, the Act ! Finale a primer in how not to stage a large Rossini ensemble.

Costumes, also designed by Mr. Sabounghi, related to WWII evidently, though the Venetian senators were cloaked in rich robes. Particularly annoying was the 30 or so female chorus all dressed as housekeeper maids who joined Bianca in throwing plastic flowers around the stage — clicking as they hit the floor.

Plastic flowers, female chorus as maids, Jessica Pratt as Bianca

It was a retro evening with much fine singing, Roberto Abbado conducting the formidable Orchestra Sinfonia Nazionale della RAI in highly informed Rossinian fashion.

Palofestival, Pesaro, Italy, August 18, 2024. All photos copyright Amati Bacciardi, courtesy of the Rossini Opera Festival.

Ermione in Pesaro

Ermione (Hermione in the Greek myth, though Rossini’s opera has nothing to do with the myth or Euripides tragedy) was anticipated with great expectations both because Michele Mariotti, Pesaro’s conducting star, was its maestro, and because the 2008 Pesaro Ermione conducted by Roberto Abbado is remembered as a very successful Pesaro production — not to forget the 1987 performances with Montserrat Caballé, Marilyn Horne, Rockwell Blake and Chris Merritt.

A Greek king, Pyrrhus is engaged to Hermione, though he has fallen in love with the Trojan princess Andromache, politically unadvisable. The Mycenaean king Orestes however loves Hermione, politically inadvisable. Hermione loves Pirro, Andromache’s son (son of Hector, seen but not heard) is a political football. Pirro will marry Andromache, Hermione vows vengeance thus Oreste kills Pirro, then escapes her wrath.

Forget love versus duty, Ermione is about rage, evidently foreign to the Neapolitan public’s expectation of opera, as the opera was pulled after only a few performances.

Ermione, cupid (silent role), Pirro

Conductor Mariotti from the first notes of the overture placed his orchestra in an extraterrestrial space, Rossini’s play of woodwinds dancing excitedly, his crescendos piling one upon another in always new instrumental colors, a chorus intruding from time to time lamenting the lost glory of Troy. The overture to Ermione announces Rossini and the Italian operatic tradition to be in avant-garde stance.

Indeed it was Rossini venturing into new territory, building complex dramatic scenes instead of opera seria’s musical numbers. This was Rossini entering into the larger French operatic world, Rossini exploring the techniques of the Gluck reforms, and Spontini’s emotional expansions. Most importantly the Rossini opera seria recitatives that had only to advance the story in other Rossini tragedies have become full blown dramatic actions filled with vocal inflections and orchestral colors.

Yet it is Rossini, the voices of the protagonists traversing finely wrought musical lines, adding the musical excitement of masterful elaboration.

The staging was entrusted to German director Johannes Erath, in a third collaboration with Michele Mariotti. Erath created a production of enormous technical complexity, in a vast expanse that spread onto a gangway both at the sides and in front of the orchestra pit [the orchestra at the venerable Vitrifrigo Arena sits floor level, old style, together with the audience].

Director Erath and his set designer Heiki Scheele actually enclosed the orchestra within the stage picture using the gangway platforms and side wall projections to break out of the proscenium arch, thereby thrusting his actors into our space.

Cupid (silent role) on gangway, white lines

Onto this vast stage panoply he then placed the actions of the story on the Trojan shores, in various grand palaces, among celestial bodes and in real places that we know well — the Teatro Rossini and the Pesaro beach. Though the intimate encounter of the jealous Hermione berating the very self possessed Pyrrhus for loving Andromache took place she on a platform at the orchestra left, he 70 feet (20 meters) away on the orchestra right, shouting at one another across the RAI Symphony.

We were there, but we didn’t know where. We did know that it was high theater, reminded by the three huge rectangles of thin white light that enclosed, singly or superimposed, stage pictures from time to time.

Ermione was sung by Italian soprano Anastasia Bartoli (no relation), a silvery voiced singer of obviously very formidable technique. She is of imposing, indeed threatening presence, and has the incredible stamina required to rage brilliantly for several hours. Dressed in a highly concocted gown of sorts (a black leotard with red side bustle skirts) she let loose at Pirro for loving Andromache, then at Oreste for not knowing that he should not have avenged her by killing Pirro.

Pirro was sung by Italian tenor (really a baritenore) Enea Scala, a singer of dashing presence, and beautiful, powerful lyric voice that infused Rossini’s expressive fioratura with confident, unflappable elan. Unfortunately the Tottola libretto kills him off early in the second act, depriving us of the potential vocal glories of many alternative outcomes, not just the Act II finale where he might have had a few things to say.

Juan Diego Flórez as Oreste, Anastasia Bartoli as Ermione

Oreste was sung by Peruvian tenor Jean Diego Flórez, skillfully, very skillfully in his famed voice declaring his love for Hermione, demanding as well that Pirro execute Andromache’s son thus avoiding that the son avenge the death of his father, the Trojan Hector. Dressed in his signature white suit the 51 year old Mr. Flórez is singing in a voice of some added warmth, making this Oreste a sympathetic, somewhat pathetic, brilliantly sung soul.

Andromache was sung by Russian mezzo Victoria Yarovaya. In the Erath staging she became an even more minor character than she had become in the Tottola libretto (loosely based on Racine’s Andromaque), and, what’s more, the original Ermione was to be sung by the great Rossini tragedian Isabella Colbran (later Rossini's wife), leaving little extra-dramaturgical excuse for additional ravings. In a white wig and rather plain gown she was more a part of the scenery in spite of her two brief, beautifully sung arias.

Of note was the non-singing presence of Andromache’s son Astianax, played by an adolescent looking young man who remained completely limp as he was dragged up and down steep steps, pulled on and off the stage — a directorially witty piece of meat whose threat to Greek security precipitated the downfall of two Greek kings, leaving on stage only the enraged daughter of the King of Sparta.

Facilitating roles were placed by Michael Mofidian as Fenicio, Martiniana Antonie as Cleone, Paola Leguizamón as Celia and Tianxuefei Sun as Attalo. The chorus of Teatro Ventidio Basso, the theater of nearby Ascoli Piceno, were the Trojans or Greeks as needed. This chorus is a formidable ensemble well able to fulfill the demands of a major production.

For the duration of the opera, conductor Mariotti held the orchestra and the stage aloft in the Rossini universe that so thrills the pilgrims to Rossini’s birthplace each year.

Vitrifrigo Arena, Pesaro, Italy, August 17, 2024. All photos copyright Amati Bacciardi, courtesy of the Rossini Opera Festival.

L’equivoco stravagante in Pesaro

L’equivoco stravagante (1811) had only three performances before it was pulled by the censors. This is the same year its 19 year old composer was hauled off to prison for his threats to whip a couple of choristers.

In Rossini’s operatic oeuvre L’equivoco is only preceded by La cambiale di matrimonio. Rossini chose a libretto stuffed with zany word play, vulgarities and "equivocal," I.e. sexual, meanings. Tasteless indeed, it was well deserving of the censor’s disgust. Meanwhile it made Rossini famous.

A silly, pretentious, nouveau riche farmer’s daughter is slanderously said to be a castrato, thus scaring off an unwanted suitor. In the spirit of the times the masterminds were sly servants who sought to make true love triumph over vanity, exploiting the laughable attempts of the farmer and his daughter to appear highly educated, as presumed, they assumed, by their wealth.

Penniless Herman loves Ernestine from afar, the servants Frontino and Rosalia determine that Herman pretend to be a professor of philosophy. Meanwhile Ernestine’s father Gamberotto plots to marry Ernestine off to the cocky (double entendre) Buralicchio for financial advantage. Ernestine just wants to go to bed with someone.

Pietro Adaini as Ermanno, Maria Barakova as Ernestina, Nicola Alaimo as Gamberotto, Carles Pachon as Buralicchio

All this played out in the 19 musical numbers created by the young composer reared in the traditions of opera buffa — cavatinas, arias, duets, plentiful trios and quartets, plus he added a unique patter quintet as well as grand finales with male chorus. The incipient brilliance of Rossini is all there, if not the polish of a finished technique and the dramatic sophistication of many of his later works.

The original, 2019 Moishe Leiser and Patrice Caurier production was mounted in the Vitrifrigo (a maker of boat refrigerators) Arena (15,000 seats) transformed into a 1100 seat, fully equipped, modern proscenium theater, a space that usually hosts the famed comedies and the grand tragedies of Pesaro’s prodigal son. The venerable 700 seat, Italian style Teatro Rossini, usually the home of minor Rossini, was closed for repairs.

Re-opened just now after a major restoration the Teatro Rossini hosted a much reduced L’equivoco, scaled to fit an early nineteenth century (1813) stage (the theater took on the Rossini name only in 1854). Now housed in an appropriate theater the Leiser/Caurier production found the vitality of the excited young composer allowing L’equivoco to become the cocky piece Rossini intended.

The intimacy of the theater thrust our attention onto the performers, as does the minimalism of the Leiser/Caurier production — a room and its ceiling within a gold proscenium picture frame, the walls covered with a repeating, large stenciled silver motif. A smaller gold frame enclosed a painting on the back wall, a cow staring us in the face (lead photo, with Ernestina). The all male chorus wore identical costumes and mustaches, and everyone in the cast wore exaggerated prosthetic noses, creating a clownish ambience where this farmer’s daughter joke could easily happen.

First it was the grandiose language that amused us, filled with ribald, double meanings, many caught by the English language subtitles, many lost. Then we were smitten by Buralicchio’s cock like costume –– a pushed out chest and a protruding butt — that crowned his lusty entrances. And finally, cherry on the cake, it was the silly, upside-down idea of a castrato pretending to be a woman that made us groan (castration was a disappearing operatic phenomenon in Rossini’s new century, mezzo sopranos taking the high voiced male roles).

The farmer Gamberotto was played by famed Rossini buffo bass Nicola Alaimo (Pesaro’s Guillaume Tell). Mr. Alaimo boasts everything you wish for a buffo — an imposing figure, a voice that can boom as well as negotiate the lightening speed of the patter when things get confusing (and there is so much to say and so little time to say it).

The farmer’s daughter Ernestina was played by Russian mezzo soprano Maria Barakova, a natural comedienne who rendered the farmer’s daughter’s lust quite urgent. This fine young singer was a participant in the Accademia Rossiniana in 2018 (the Rossini Festival’s training program) and has since developed an impressive career in major Western theaters.

The cocky Buralicchio was played by Spanish baritone Carles Pachon. This young artist exuded the cocky confidence of his costume, finding all the considerable courage needed to confront an artist of Mr. Alaimo’s stature. A recent participant in the Berlin Staatsoper he is now a member of that company.

Ermanno, the penniless suitor, was sung by Italian tenor Pietro Adaini, also a recent participant in the Accademia Rossiniana. He was confused as needed, then able to pull himself together to impersonate a philosophy professor, and finally to rescue the imprisoned Ernestina and pile into bed with her.

The farce’s instigators, Gamberotto’s sly servants, were played by Patricia Calvache as Rosalia and Matteo Macchioni as Frontino.

Nicola Alaimo as Gamberotto, men of the chorus of the Teatro Della Fortuna as housekeepers

Italian conductor Michele Spotti conducted Pesaro’s Filarmonica Gioachino Rossini, offering from time to time the very great satisfaction of a fine Rossini delirium. The men of the chorus of the Teatro Della Fortuna of Fano, a nearby town, gamely scratched at their flea bites, a comic conceit inflicted by the directors, while singing with Rossinian pizazz.

Teatro Rossini, Pesaro, Italy, August 16, 2024. All photos copyright Amati Bacciardi, courtesy of the Rossini Opera Festivald.

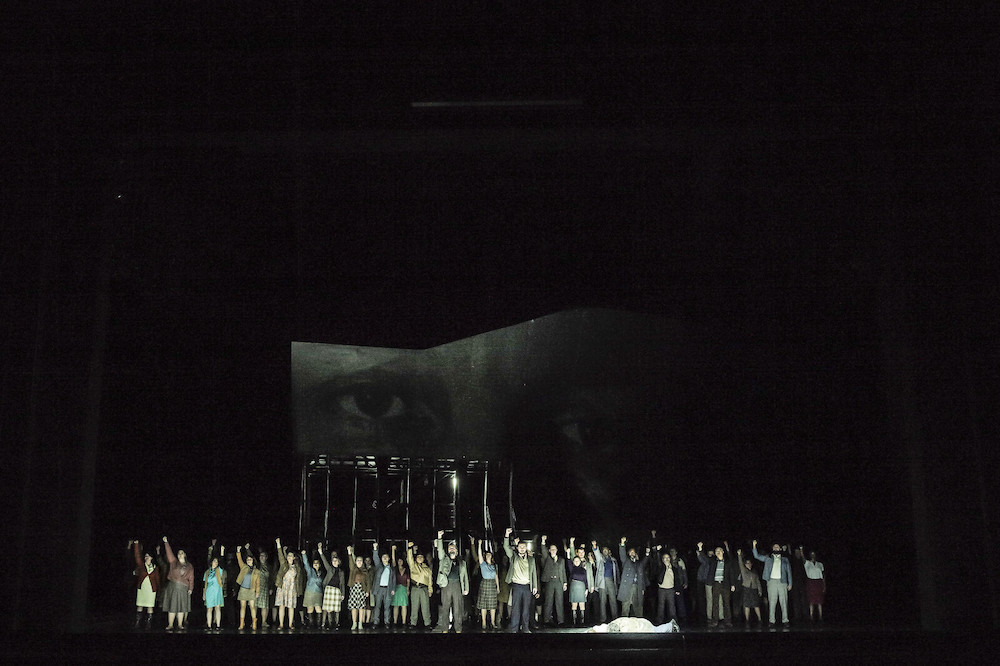

The Idiot at the Salzburg Festival

The Salzburg Festival’s Felsenreitschule is home to most of its productions of twentieth century opera, just now two Russian operas based on novels by Fyodor Dostoevsky — Mieczyslaw Weinberg’s The Idiot (1987, though premiered in Mannheim in 2013), and Sergei Prokofiev’s The Gambler (1917, though revised for its 1929 premiere at Brussel’s Monnaie).

Both Dostoevsky novels, The Gambler (1866) and The Idiot (1868/69), are at least somewhat autobiographical, the events and personages of his life are amplified in the urgencies developed in both novels. Dostoevsky had indeed lived for a time in Switzerland, he suffered from epilepsy, had a gambling addiction, begged money from his family, fell in love with a woman named Polina, etc.

Given operatic advance planning it is likely that this 2024 double Rock Riding School programing was conceived before Russia’s February 24, 2022 bet that it could take Ukraine in a day or so. That bet lost, things Russian have lost their luster for westerners, Dostoevsky’s exposition of the Russian psyche adding no polish whatsoever to the tarnished Russian image.

When becoming operas both The Idiot and The Gambler lose much of their nineteenth century ambience, the reduced plots and personages sacrifice much Dostoevsky tonality. Both operas are more like short stories than they are like novels, short stories thrusting a formed character into a situation then finding a resolution. Both Prokofiev and Weinberg then color their stories with the modernist compositional tendencies of their time — think Igor Stravinsky and Dmitri Shostakovich.

As do directors when they stage their operas.

The Salzburg Festival entrusted the staging of The Idiot to Polish director Krzysztof Warlikowski, his designer wife Maľgorzata Szczęśniak and their team, video designer Kamil Polak and lighting designer Felice Ross. The Rock Riding School is a vast expanse of stage in front of a cliff. Ignoring the cliff Warlikowski erected a long (very long), low, polished wood cross-stage wall, embedded within it was a large screen for projections, plus there was the usual Warlikowski box that rolled out for intimate, domestic scenes — the murder of Natascha as example.

The libretto, construed by the composer, closely follows the novel, losing only a few extraneous characters. The idiot, a prince who is a perfect Christian, meets a man of affairs on a train who is smitten by a femme fatale. Their lives become entwined as they both follow Natascha (the femme fatale) through her brief, twisted life and inevitable death.

Video by Kamil Polak Video, lower image Bogdan Volkov as the Idiot

Composer Weinberg escaped Poland during the WWII German invasion, fleeing to Russia where he lived a rich, musical life as a Soviet composer. Of his seven operas he considered The Passenger (1968) to be his best, in fact to be the most important of all his works, though the opera had its premiere finally in Germany in 2006. Weinberg’s works have been rediscovered only in recent years,

Stylistically Weinberg is similar to Shostakovich, though without the sarcasm. More sumptuous than Shostakovich he mixes free tonalities, atonalities and polytonalities in often hugely complex rhythms. His vocal lines are melodic, if not flowing, requiring singers of considerable technique with precise ears. Weinberg’s orchestra for The Idiot was huge, unleashed under tight control by Lithuanian wunderkind conductor Mirga Graźinytè-Tyla — she is the current music director of the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra.

Bogdan Volkov as the Idiot

Composer Weinberg takes nearly four hours to tell his tale. Of great orchestral moment was the Idiot’s epileptic seizure, requiring all possible virtuosity from the Vienna Philharmonic to support the massive seizure grandly, indeed grotesquely enacted by Ukrainian lyric tenor Bogdan Volkov, a singer of beautiful voice, great presence and phenomenal stamina. Mr. Bogdan’s subtle acting skills were well matched by Lithuanian soprano Austrine Stundyte (Warlikowski’s 2023 Salzburg Elektra) as Natascha, who, staring directly into a video camera, created shockingly direct femme fatale portraits (lead photo) that were projected onto the huge wall screen. The sheer intensity of these images equaled in effect Mr. Bogdan’s epileptic fit that came much later.

Mme. Stundyte, an extraordinary artist of magnetic presence, then disappeared under unfortunate wigs that greatly diminished her persona. Her murderer Rogoschin was played by Belarusian baritone Vladislav Sumlinsky, capturing the intensity of his obsession with an overtone of perverted Russian humanity.

Rogoschin’s rival to buy Natascha was the desperate Ganja, played in heroic voice by Slovakian tenor Pavol Breslik. Aglaja, Nataschia’s rival for the attention of the Idiot was well sung by Australian mezzo soprano Xenia Puskarz Thomas. Dostoevsky’s busybody, civil servant Lebedjew, who knew everyone and everything in Warlikowski’s generically stylized, modern Russian-esque world, was made into a fantastic joker/magician, the role gamely played by Ukrainian tenor Iuril Samoilov. Among other gold-plated casting was British bass Clive Bailey as Aglaja’s father.

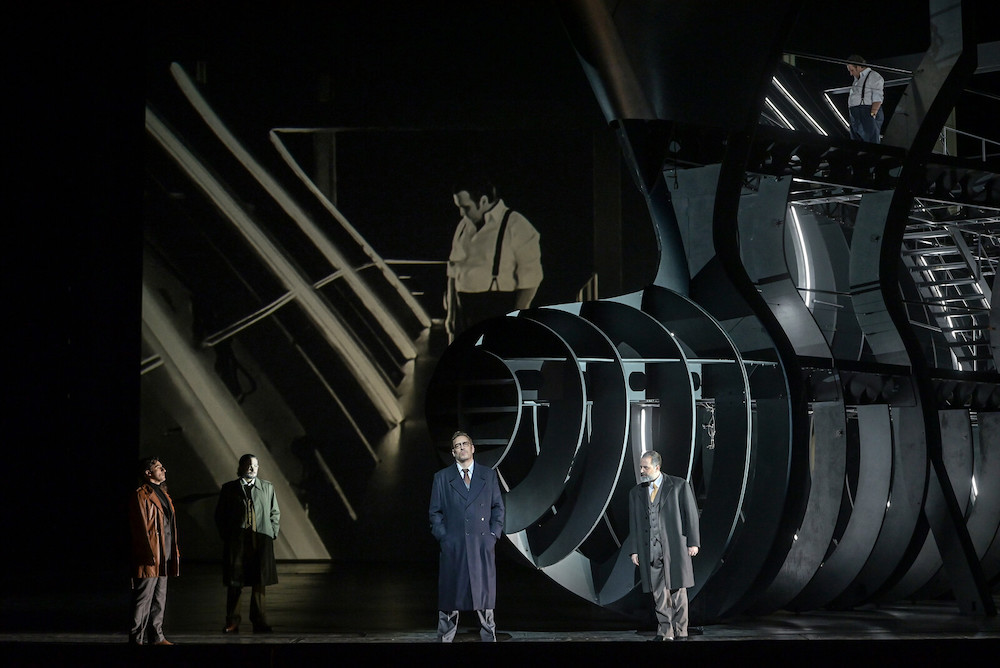

The Gambler at the Salzburg Festival

Sean Panikkar as Alexej, Asmik Gregorian as Polina

The Salzburg Festival entrusted the staging of Prokofiev’s The Gambler to American wunderkind (now age 66) director Peter Sellars and his usual Salzburg associates, set designer/architect George Tsypin, lighting designer James F. ingalls, and costume designer Camille Assad. [See also my introduction to The Idiot]

Prokofiev greatly simplified and streamlined the plot of Dostoevsky’s The Gambler. The composer reduced its actors to the ten needed to achieve an operatic action. Director Sellars then turned the Dostoevsky nightmare into a quite breezy account of some nasty doings by some not very appealing characters. The opera was a few minutes more than two hours in length. Mercifully.

Of course Peter Sellars updated and politicized the happenings — cell phones and emails abounded, pro-environment protests, and surely even more moralizing beyond the opera’s hero (so-to-speak) Alexej’s condemnation of capitalism, and the world’s devotion to money. All this mattered very little as we were busy trying to keep up with the banter that moved the story along, getting us finally to the climax the evening — the absolutely spectacular roulette scene where Prokofiev added 15 additional solo voices to celebrate Alexei breaking the bank at the roulette tables.

Sean Panikkar at the roulette table (center), croupier and onlookers

[Polina, whom Alexei loves, then refused the 50,000 rubles offered by Alexei, the amount she had wanted to throw in the face of the Marquis, one of her debtor benefactors].

The roulette scene is a compositional tour de force by the young composer, building the excitement of spinning roulette wheels while interweaving the voices of the excited players, croupiers, onlookers, losers, etc., resulting in a musical orgy that finds the climatic colors and rhythmic excitement of the Stravinsky ballets for famed impresario Sergei Diaghilev that took stage in France during Prokofiev’s formative years.

[Diaghilev in fact met Prokofiev in London in 1915, commissioning the young composer to create a ballet, advising him to stick to Russian themes. The ballet Chout (The Buffoon) appeared in 1921].

Young (30 years) Russian conductor Timur Zangiev urged the Vienna Philharmonic and an ensemble of exceedingly well-rehearsed singers to a frenzy of musical excitement that equaled the light show unleashed on the stage by Sellars’ lighting designer James F. Ingalls, as the many, outsized spinning tops (roulette wheels) that were the riches everyone lacked, went airborne, whirling like flying saucers. Fog machines released clouds of vapor that shown dramatically in the lightning quick changes of full stage color.

Sellars’ set designer George Tsypin, besides creating the huge tops, opened up the galleries carved into the massive cliff behind the Rock Riding School stage, filling them with digital screens where we watched the audience (capitalists all) enter the theater, though he hung a heavy green covering over a few of the lower galleries so that there could be a space for scenes outside the casino. Intimate scenes were simply acted out down stage center in focused lighting.

[Though he may have lost Polina Alexej marveled mightily at the run of luck he had].

I’m not sure who the title gambler really was, maybe it was the debt ridden faux general, broadly acted and sung by Chinese bass Peixin Chen, whose rich grandmother was supposed to die but instead lost most of her fortune at the roulette wheel — played by Lithuanian mezzo soprano Violetta Urmana. Probably the gambler was the university student Alexej who had all attendant progressive attitudes, though he learned finally that money could not buy love, though it was thrilling to be a winner. American tenor Sean Panikkar made this foolish, love sick student quite real.

Polina, the General’s ward, had many transactional relationships — among them the faux Marquis and his accomplice Blanche, played respectively by French character tenor Juan Francisco Gatell and Ukrainian mezzo soprano Nicole Chirka, and the rich Brit Mr. Ashley played by Madagascar baritone Michael Arivony.

She, Alexej’s femme fatale, was played by brilliant Lithuanian soprano Asmik Gregorian (Castellucci’s Salzburg Salome, and Warlikowski’s Salzburg Chrysothemis). Possessed of magnetic personal presence, and of powerful, dramatic voice this unique artist was superfluous to this character, and to this production — she was not the promiscuous, teasing student, ensemble singer that director Sellars envisioned. Mme. Gregorian is a diva.

Tristan und Isolde at Bayreuth

It is a Tristan well worthy of the Wagner shrine (not all Bayreuth productions are). Icelandic theater director Thorleifur Örn Arnarsson imposed a truly hermetic discussion of love onto the Wagner masterpiece in the rarefied theatrical terms of Berlin’s hyper avant-garde Volksbuhne (of which he was a recent artistic director).

Richard Wagner’s unique Bayreuth Festspielhaus hides the orchestra under the stage, voice and orchestral sound flow into the hall as one. The Bayreuth cast was peerless, the orchestra shone in the theater’s acoustical magnificence. Czech conductor Semyon Bychkov accommodated the highly inflected text with an equally highly inflected orchestral score — voice and sound symbiotic, in complex textures that magically challenged the ear.

The stage itself challenged the mind — Isolde in white wings on a huge white cloth (clouds or the boiling sea) on a blank stage in the first act, in the second Isolde and Tristan were lost in the ruined hull of a ship, a cluttered attic of earthly items. The third act emptied much of the attic, leaving only some sculptural bones of its hull that basked in the transcendent light of a golden Liebestod.

Act I

There was no synopsis in the program booklet, only an explanation of how Tristan and Isolde found themselves together on a ship to Cornwall, and an essay by Nike Wagner (Wieland’s daughter) who notes that “if Thomas Mann thought that Tristan, not unlike the Ring, conceals a ‘cosmogonic myth’ he must be corrected insofar as this cosmogonic myth, in the end, is concealed through compositional measures that guarantee regression.”

Be that as it may, the Arnarsson production played heavily on the complexities of love — its deceits and deceptions that are the sum of the first act, the paradox of the second act when the union of love is the death of the lovers, and the third act when Isolde has in fact has failed to lead Tristan to the death she had promised him when their gazes first met — all this before this Wagnerian treatise began.

The above Tristan primer is the manifest of this Arnarsson staging, enacted in small, subtle, symbolic gestures and images that were felt rather than defined — Isolde entrapped within her cloud in the first act Tristan tearing papers apart in the second act, the white dressed steersman with wings appearing and disappearing in the third act — to mention the more obvious of the plethora of images of separation and death.

There were blatant departures from Wagner’s stage directions, departures that illuminate the critical discussions that this Wagnerian opera has engendered over the past 168 years — we are well aware that this opera is not the same opera it was in 1857. In the first act Isolde tore the flask of poison/love potion from Tristan and threw it across the stage — the original gaze was in fact the Tristan death poison (in the opera’s pre-history Isolde was about to kill Tristan when their eyes met in the gaze of immortal love). The second act ends not with Melot wounding Tristan but with Tristan drinking the potion Isolde had given him to heal his wound in the pre-opera history, thus again saving him only to endure her promised love death.

The intended force of these images and their shattering effects determined that much of the stage action was static, the singers left alone to intone the text, to inflect the text with subtleties of intention that was subservient to the philosophic imagery perceived by Aransson and contemporary Wagnerian criticism.

Much the same process occurred in conductor Bychkov’s reading of the score. If the perception was that the progression of text (stage action) was slow, nearly static (and indeed it was), so were the maestro’s tempi. But the slowness brought forth the revelation of colors from within the depths of Wagner’s orchestration, often forcing apart the orchestral sounds from the voice sounds in the shattering chromatic dissonances of separation. This the antithesis of the conjunction of love that was once thought to be the proclamation of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde.

Freed to declaim Wagner’s text the singers inflected the text, often sacrificing an expected musical flow. The moments of illumination they felt flew easily, the deceits were spat, the joy was shouted, the negotiations were brutal. Of great moment was the Tristan of Austrian tenor Andreas Schrager (lead photo with Kurwenal) who drew upon his myriad voices to create a Tristan of monumental dimension, from an intoned speaking voice to full throttled shouts of joyous illumination in his third act recalls of the conjunction he might have had with Isolde. In the second act his emphatic accents as the excitement of love-death approached were truly momentous.

Act III

Isolde was enacted by Norwegian soprano Camilla Nylund, who crawled across the stage to sing her "Liebestod" propped up against a broken ship beam, the stage of broken ship beams bathed in golden light, the stage platform itself floating on golden light. Mme. Nylund possesses a quite beautiful voice of silvery color. With soaring high notes she found as well the vehemence needed for her Act I condemnation of Tristan.

Marke was sung by Austrian bass Günther Groissböch who delivered his famed Act II soliloquy with lieder delicacy, inflected with such grace as to render it timeless. Icelandic baritone Ólafur Sigurdarson was the beautifully voiced Kurwenal, lending authority to Tristan’s plight as Wagner required. Brangäne was sung by Austrian mezzo-soprano Crista Mayer in great warmth and power of tone. Bass baritone Birger Radde, in black pants and a fancy black shirt, flashed impressively on-stage as Melot in the finales of Acts II and III.

The sets were designed by frequent Arnarsson collaborator Vytautas Narbutas. Lighting designer Sascha Zauner was the Arnarsson collaborator for the recent Parsifal in Hannover. Costumes were created by Arnarsson collaborator Sibylle Wallum.

Festspielhaus, Bayreuth, Germany, August 9, 2024.

Der Fliegende Holländer at Bayreuth

Like all productions by Russian revisionist stage director Dimitri Tcherniakov, the Bayreuth 2021 Dutchman production is fraught with meaning, delving deeply into the contemporary resonances he discovers in nineteenth century opera.

This current revival of his Bayreuth Holländer production is enriched by the musical presence of Ukrainian conductor Oksana Lyniv. Mme. Lyniv has much experience with this early Wagner masterpiece, first in Barcelona in 2017, and now, in the Tcherniakov production, every year at Bayreuth since 2021. Thus her very colorful, very direct connection to the opera’s heroine Senta can come as no surprise, though it remains always shocking in effect.

Tcherniakov staged the Dutchman overture as a dream in which the Holländer, as a young boy, watches his mother solicit then have sex with Senta’s father Daland. He watches as the mother, prostituting love, is ostracized by the villagers. In sudden, brutal reaction the mother hangs herself. Discovered by the boy Holländer, he toys with her dangling feet, a Wozzeck-like “hop! Hop!” quote.

Did I get this right? At Bayreuth there are no concessions to an international audience. Bayreuthian hermeticism insisted that the German words projected on a scrim defining the overture’s dream remain untranslated.

Thus the dream informs us that the opera itself will be the Holländer’s revenge on love — not the celebrated Wagnerian ideal of pure love (endlessly discussed in the current Bayreuth Tristan), but love in its most basic bestial and transactional forms. In true Tcherniakov form the Wagnerian tale then became the most tense, cruel moments in the lives of a small Bavarian family in a small Bavarian village. Or somewhere.

At the August 8 performance I attended the Dutchman was portrayed by Polish/Austrian bass-baritone Tomasz Konieczny instead of the announced German bass-baritone Michael Volle, a cast change that greatly enriched and perhaps confused the tonality of the Tcherniakov concept.

Tomasz Konieczny (no photos available) possesses a voice of great presence, of piercing color, a voice that is sexual and predatory. He has a handsome, commanding and authoritarian bearing, becoming a dangerous, fantasy figure. It is as such that he arrived at the village bar/pub where he aggressively expounded his male solitude, attracting the attention of Senta’s father Daland, portrayed by warm, paternally voiced German baritone Georg Zeppenfeld, who has a daughter of marital age.

But Tcherniakov’s Dutchman as portrayed by Mr. Konieczny became less about the Holländer’s revenge, and more about the values of village life, and the force of human instinct that conflicts with such values. Senta possesses such wild, youthful instincts. Her father and mother — in Wagner’s libretto this is Senta’s nurse, Marta — are the family, with its attendant need of wealth and continuity. Marta, as Senta’s mother, was sung by appropriately figured and voiced German (Indiana University trained) mezzo soprano Nadine Weismann.

The spinning chorus in Tcherniakov’s world became a chorus of village women, conducted by Marta, extolling the domesticity of simple life. The rehearsal was brutally interrupted by the fiery Senta, sung by Norwegian soprano Elizabeth Teige with impressive, impatient attitude. Mme. Teige posses a quite beautiful voice that she used with consummate, aggressive skill expounding her quite spectacular ballad telling of the Holländer’s quest for eternal love. She too, in her troubled sexual fantasies seeks love, adding considerable interest to Tcherniakov’s domestic tragedy, echoing the early twentieth century Janacek tragedies.

Senta’s father and mother invited the Holländer to dinner to introduce him to their daughter, a fruitful marriage in their minds. Falling under the Holländer’s spell, Senta needed no such encouragement, though the mother, silent in this scene, became visibly troubled.

Senta however had already pledged her undying love for the villager Eric (lead photo), sung by American Heldon tenor Eric Cutler, who cut loose in fine, heroic voice with his impassioned expectations of Senta. She summarily repulsed him — physical brutality is a Tcherniakov forte. More brutality ensued. The villagers, led by the town drunkard (Wagner’s Steersman, sung by American Helden tenor Matthew Newlin), confronted the band of unknown forces that accompanied the Holländer’s arrival in the village with much bloodshed. This excitement was greatly heightened by the chorus keeping up with the maestra’s breakneck speed for this splendid scene (they did).

At last the Holländer is forced to confront Eric, two powerful male voices, the denouement to unfold, though in the Tcherniakov production there is no ship on which the condemned Dutchman can escape. Marta the mother suddenly appears with a rifle and shoots dead the Holländer, Eric and Senta are left standing on the stage, the myth forgotten as the village is being consumed in flames, Gotterdammerung-like, all this to Wagner’s grandiose music for Senta’s suicide, a death meant to free the Holländer from his cruel fate.

This Tcherniakov denouement, of the many that occur at European opera festivals, is among the richer, laden as it is with Wagnerian humor.

Tcherniakov himself created the setting — a group of village-like bare structures, that, like the villagers dancing in Act III, danced around the stage in varying configurations for the varying plot complexities. These stifling variations were joyously supported by the maestra’s surprising discovery of many bright dance rhythms in the Wagner score. The complex, spectacular lighting was by Tcherniakov collaborator Glen Filshtinsky, the costumes were designed by long-time Tcherniakov collaborator Elena Zaytseva.

Michael Milenski

Wagner Festspielhaus, Bayreuth, Germany, August 8, 2024. All photos copyright Enrico Nawroth, courtesy of the Bayreuth Festival.

Il ritorno d'Ulisse at the Aix Festival

Pierre Audi, the artistic director of the Aix Festival, completed the Aix Festival’s Monteverdi cycle just now by staging, himself, this Il ritorno d’Ulisse (1640). L’Orfeo (1607) was staged by American choreographer Trish Brown in 2007, L’incoronazione di Poppea (1643) was staged by American stage director Ted Huffman in 2022 — thus the three extant (of seven) operas by Monteverdi, the founder of modern, intoned tragedy.

Though born into the Mediterranean world, in Lebanon, Pierre Audi came to Paris as a teenager, then completed his education at Britain’s Oxford in 1977. Eleven years later (1988) he was named head of Dutch National opera and in 2005 the Holland Festival as well. In 2018 he returned to the Mediterranean world as the artistic director of the Aix Festival, a position he now holds in tandem with the same position at New York City’s gigantic performance space, the Park Avenue Armory.

Audi staged Il ritorno d’Ulisse at the Dutch National Opera some 30 years ago, and the entire trilogy as well. He now brings Il ritorno to the Aix Festival’s tiny, 500 seat, 1787 Théâtre du Jeu de Paume for only five performances. Working with famed lighting designer/scenographer Urs Schönebaum he accordingly reduced the scale of production to the bare minimum — three neutral brown walls that assume varying positions, though there was maximal use of light — insisting that the opera is simply the return of Ulysses, first into the arms of his son Telemaco, and finally into the arms of his wife Penelope. Nothing more.

Like all Monteverdi operas Il ritorno is intoned speech. The heightened speech is often highly embellished, and sometimes it is formalized into larger musical structures. Argentine/Swiss conductor Leonardo Garcia Alarcón assembled a massive continuo to support and color Monteverdi’s emotional speech — two huge Italian harpsichords, two organs, harp, two gambas, two huge lutes, adding viols, reeds, percussion, and most importantly three trombones to build the grand orchestral colors that substitute for scenery in this minimal take on the Monteverdi masterpiece. The Cappella Mediterranea was here composed of 18 players [the same ensemble had 11 players for the 2022 Poppea].

Stage director Audi confronted the formidable, assumed problem that no one in the audience understood Italian, and that only one of the eleven member cast was actually Italian, by staging the opera in the broadest possible terms. Richly dressed Penelope bathed always in a golden light, alone in her morbid suffering, Ulysses in heroic undress, his powerful physic apparent, he too alone on the stage (lead photo). Ulysses’ son Telemaco (lead photo) and his faithful friend Eumete spoke (sang) their lines in simple dress, appropriate to their roles.

The richly dressed gods too were alone on the stage, though always with a soaring, symbolic line of white light.

The disruptive forces to Ulysses family life, symbolically his homeland, were all in neutral black dress (save the glutton Iro who was all white). These dark forces were the quarreling young lovers Melanto and Euromaco, and Penelope’s oily suitors.

Marcel Beekman as Iro (on floor, extreme left); moving left to right Joel Williams as Eurimaco (back of); Alex Rosen as Antinoo (a suitor); Giuseppina Bridelli as Melanto; Paul-Antoine Benos-Djian as Anfinomo (a suitor); Deepa Johnny as Penelope; Petr Nekoranec as Pisandro (a suitor); John Brancy as Ulysses (foreground)

Only the symbolic creatures of Monteverdi’s prologue — Love, Time, Fortune and Fragility — vying for attention, touched one another. At the first notes of the prologue they hit the walls and fell to the floor, making violent, tender, and questioning physical contact, two males and two females crawling and climbing over one another while reciting their lines. This orgy was the only touching until Telemaco fell into his father’s arms at the end the first part, and Ulysses and Penelope embraced, but only at the opera’s very final note, Ulysses return.

You may not understand Italian, and yet you did, the singers delivering their lines with unrelenting intensity, their voices quite independent of the continuo below, confidently alighting on elongated tones that were emphatically dissonant to the sound beneath them. The musical content was so complete that text and subtext became one, the story stripped of any distraction from its focus on the return of Ulysses into arms of Penelope.

American baritone John Brancy sang a truly heroic Ulysses, in a strongly present, brightly focused masculine tone, Omani mezzo soprano Deepa Johnny sang Penelope in the confident voice of a beautiful, mature woman who greatly relishes her sorrow, Southern California tenor Anthony León sang Telemaco in the clear, innocent tones of youth.

Merging the divine world with the human world American bass Alex Rosen sang Neptune raging against Ulysses in sharp tones, finding a much warmer voice for Antinoo, the most pressing of the Penelope suitors. British tenor Mark Milhofer was the placating voice of Giove, and, with a maturity of voice and artistry, he beautifully intoned Ulysses’ faithful friend, the shepherd Eumete. Argentine soprano Mariana Flores sang Minerva, the Olympian protectress of Ulysses.

Italian mezzo soprano sang Melanto, enumerating the pleasures of love to Penelope’s deaf ears, arousing the jealousy of her lover Eurimaco, sung by British tenor Joel Williams. Czech tenor Petr Nekoranek brought fine strength of tone to the suitor Pisandro, French counter tenor Paul-Antoine Bénos-Djian gave strong alto tone to the suitor Anfinomo, adding a bit of urgent desperation to the voice of Human Fragility in the Prologue.

Adding to Monteverdi’s fresco of court characters was the glutton Iro who gained the stage finally to bemoan his plight. The role was obligingly humanized by Dutch character singer Marcel Beckmann.

The cast was cannily matched, their distilled emotions clearly, directly articulated from the stage of this tiny theater, their world created and hugely enriched by the players of conductor Alarcón’s Capella Mediterranea, the creators of this musical edition.

It was an extraordinary event, greatly complementing the intelligence of this year’s festival. In his directorial notes in the program booklet Pierre Audi suggests that the Mediterranean world will forever be disturbed, its clash of civilizations created by its shared shores. Its displaced populations will always seek their homeland.

Monteverd’s Il ritorno d’Ulisse tells us only that this Mediterranean hero returned somewhere, not that he found his homeland.

Théâtre du Jeu de Paume, Aix-en-Provence, France, July 23, 2024. All photos copyright Ruth Walz, courtesy of the Aix Festival.

Eight Songs for a Mad King at the Aix Festival

That’s Eight Songs for a Mad King (1969) by Peter Maxwell Davies and Kafka-Fragmente (1987) by György Kurtág, an inspired pairing by Pierre Audi, the artistic director of the Aix Festival who directed György Kurtág’s only opera Fin de Partie (Beckett’s Endgame) for La Scala and Dutch National Opera in 2018.

A violin unites the two pieces. The seventh song of Davies’ monodrama instructs the singer to smash a violin. The Kafka-Fragmente — 40 brief statements from Franz Kafka’s diaries — is a duet for soprano and violin. Though in Aix, in the seventh song the mad king seemed to shove the violin up his ass, awaiting the end of the cycle to smash it to bits. Late in the Kafka cycle the soprano appropriated the instrument of the violinist, awakening our fear as to what might be its destiny. The gesture was, however, merely rhetorical.

It was a star-studded evening in Aix’s tiny Théâtre du Jeu de Paume, presided upon by famed German director Barrie Kosky and famed German lighting designer Urs Schönebaum. In the pit for the Eight Songs were five members of Paris’ Ensemble Intercontemporain, with conductor Pierre Bleuse. The mad king (George III) was sung by German baritone Johannes Martin Kränzle, Glynddebourne’s upcoming Amfortas (Parsifal). The Kafka soprano was Austrian-British soprano Anna Prohaska, Munich’s Anne Trulove (The Rake’s Progress). Moldovian-Austrian violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja, impressively connected to current avant-gardism, completed the cast.

Peter Maxwell Davies (1934-2016) was a 1960's English enfant terrible of a newly energized avant-garde fueled by the protests taking place in Europe and the United States. Not that the Davis Songs are protesting much of anything other than offering a moment of what was perceived back then to be artistic outrage. A further connection between the Songs and Fragments is mental illness — the librettist of the Davis Songs, Randolph Stow had been suffering from depression, as, famously, Kafka suffered from depression, not to mention the mid 1950's depression of Hungarian composer György Kurtág that rendered him a minimalist.

Kurtág, now 98 years old, is the last living composer connected to the post-war avant-gardism of the last century, and that of Peter Maxwell Davies. Not that this staging of the Songs and the Fragments sought to evoke the 1950’s when everyone was indeed depressed. Instead messieurs Kosky and Schönebaum made these songs and fragments into an artistic upper, stripping both pieces of any dark colors, leaving only the excitement of artistic discovery — Davies finding solace in outrage and Kurtág indulging himself in minimalism.

Baritone Johannes Martin Kränzle

For this Mr. Schönebaum created a black void, Mr. Kosky stripped the mad king to his white briefs and banished the six instrumentalists to the pit. They imagined stage movement for the Kurtág concert piece in the same void, its performers in identical, simple grey dresses, the only prop was a violin.

A shattering explosion introduced Davies’ Songs, then a single spotlight illuminated the face of the mad king as baritone Kränzle began to sing, his voice traversing a range of four or five octaves in screeches, wails, whimpers and howls, with the conviction of a mad king willing to bare it all — including his the nearly naked body. It was a total performance by Mr. Kränzle that charmingly embraced state director Kosky’s penchant for the obscene as well — placing Mr. Kränzle's hand inside his underpants, a finger emulating an erected penis, then humping the proscenium arch.

For the half hour duration of the songs Mr. Schönebaum’s only illumination of the artist was his face and his body. It was a monumental feat of lighting, and an amazing display of the prowess of the technician who followed the mad king throughout the void. And a monumental achievement of mind and voice by baritone Kränzle.

The Kafka diaries, the source of Kurtág’s texts, are often amusing, seeming to be stray thoughts, self-doubts, internal dialogues, dreams, character sketches, etc. Kurtág divided his duet into four sections that were demarcated by changes in way Mr. Schönebaum lighted the artists and Mr. Kosky moved the soprano, always keeping the violinist placed a bit lower on the right. The soprano moved all over the stage in various poses, sitting sometimes on its edge, leaning agains the proscenium, embracing the violinist.

Upper right corner Lodovic Tézier as Boccanegra, his video image in center. Below left to right Charles Castronovo as Adorno, Alejandro Baliñas Vieites as Pietro, Mika Cares as Fiesco, Étienne Dupuis as Paolo Soprano Anna Prohaska and violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja

The final section of the Fragments grew to impressive dimension with the addition of slender columns of light deployed on the stage, and finally a magical white light spread across the floor — lighting effects that evoked quite effective visual excitement.

The 40 Kurtág fragments vary in duration between a few seconds and a few, very few minutes, a total duration of about one hour. Mesdames Prohaska and Kopatchinskaja flashed in and out of the light that marked each of the fragments, Mme. Prohaska somehow finding a new position in the blackout from where to sing the following fragment. Both performers, lovely women, exuded great charm, often communicating by sight, Mr. Kosky’s device for rendering his staging into an organic duet, the violinist even sometimes mouthing the words of a song. It must be said that Mme. Prohaska’s performance was a monumental accomplishment of mind and voice.

It was a splendid evening, of great nostalgia for the lost world of twentieth century avant-gardism. The Kosky/Schönebaum production discovered a new perspective on the troubles of the last century, finding its artistic excitement, not its traumas.

Théâtre du Jeu de Paume, Aix-en-Provence, France, July 12, 2024. All photos copyright Monika Rittershaus, courtesy of the Aix Festival.

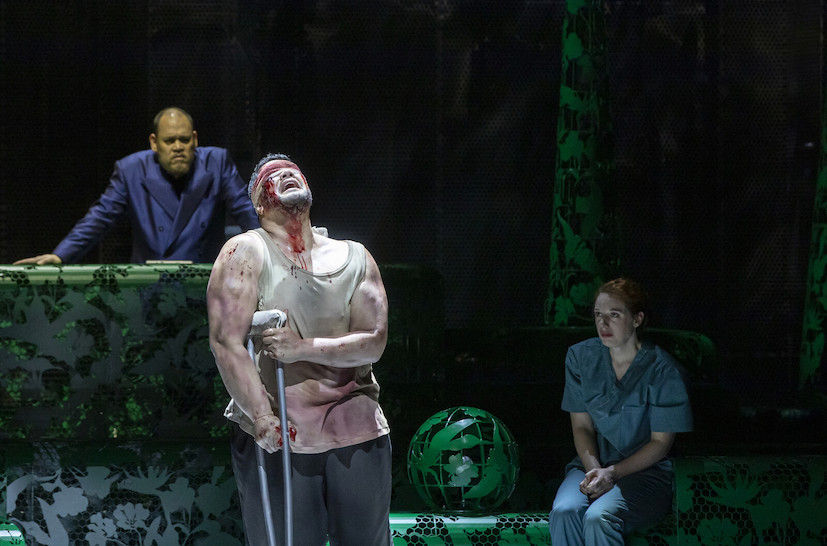

Samson at the Aix Festival

Rameau’s Samson, with the libretto by François-Marie Arouet aka Voltaire, or rather a sort of Rameau/Voltaire Samson imagined by French early music conductor Raphaél Pichon and German stage director Otto Guth, a dream team imagined by Aix Festival artistic director Pierre Audi.

Pichon and Guth landed on Rameau’s Samson, an opera that had never been performed though it had been rehearsed, and for which a score no longer exists. Voltaire’s libretto does however exist, but only in a version he created late in life when he no longer wished to be polemical.

While the Samson tale is biblically based, Voltaire had introduced a few tawdry love affairs, and turned Samson’s famed destruction of the Philistine temple into an act of angry desperation, hardly one of religious fervor. The censors found the libretto to be sacrilegious.

As any sensible composer would, Rameau simply re-purposed many pieces from Samson into future operas.

Conductor Pichon with stage director Guth imagined a theatrical action that unfolds quite independently of the published Voltaire libretto, though they maintain that their Samson is well within the spirit of a plausible Voltaire/Rameau Samson, if not the letter. Pichon took on the musical archeology needed to construct a Samson-sounding score, using appropriate bits and pieces of 17 (or so) other operas and ballets by Rameau. These lifted bits cannily approximate the words that might have been uttered by the 1735 Samson singers, the stage actions imposed by the Guth/Pichon production were now those of the Samson story.

The program booklet informs us that messieurs Pichon and Guth felt compelled to include a French Baroque haute-contre voice, given that the original Samson creators took the audacious step of making the opera’s hero a baritone, not the usual tenor. Thus they created the haute-contre role of Elon, Samson’s best friend, who, shocked and horrified at Samson’s impulsive, destructive nature turned Philistine.

While the genesis of this in-the-spirit-of Rameau opera may be fascinating, we are confronted with the actual experience of its performance. Stage director Guth, as he had with his 2022 Aix Festival Dante, il viaggio, felt the need to add a cornice to the opera. For Dante, il viaggio it was a shockingly intrusive, terrifying automobile accident, for Samson it was the addition of a speaking role for Samson’s old mother who spoke the story, with visions of the once young mother, babe-in-arms, and the boy Samson at various ages.

Jarrett Ott as Samson, Lea Desandre as Timna (the first of two love affairs)

Guth placed the action in a heavily distressed building of neoclassical design, and employed three current architect types to appear from time to time to plot its reconstruction. Thus motivated were the blue laser lights to measure distances that played on the structure from time to time, the vertical red line that swept across the stage from time to time, and the descending bar of intense white light that marked scene closures (falling on Samson in lead photo). To this superimposed light show, Guth added huge electronic sound effects (amplified percussion) when he wished to sonically convey massive, destructive force.

To complete this hyper present, pseudo contemporary stage picture, Guth meticulously costumed his principals in abstracted biblical garb, but reduced his chorus and dancers to abstracted all black dress when they were Philistines and all white dress when they were Israelites. The chorus participated in the action either from the stage in costume or were hidden in the back of the pit, camouflaged in concert blacks.

Such theatrical tricks, among many more as well, beguiled us through this stunning exposition of Rameau’s music for the theater, when the Guth tricks did not irritate us.

Raphaël Pichon is the conductor and artistic force behind the chorus and orchestra ensemble named Pygmalion, based at the Opéra de Bordeaux. For this Baroque opera its choral voices were termed the dessus (soprano), haute-contre (alto tenors), tailles (baritone) and basses, its orchestral players performed on instruments of the French Baroque (though other times its instruments may be of the Classical or Romantic periods). It is an ensemble of exceptional polish and impeccable technique.

Rameau is famed as a symphonist. The Pygmalion orchestra, here comprised of 33 strings, quadruple winds, some brass, continuo and percussion, was capable of both massive force, raging sound and passionate feelings in a huge spectrum of colors. Rameau is equally famed as a composer for harpsichord (a chamber music instrument), explaining the beautifully ornamented intimacy of his arioso recitatives enriched by a rich continuo, these occurring particularly in the first part of the evening.

The compendium of Rameau pieces flowed as a seamless whole, though the first act did not find a dramatic or musical unity. The second part of the evening, with the introduction of Dalila took on an unrelenting brutality interspersed with balletic orchestral movements that took sublime flight as pure music, proving Rameau to be among the pantheon of great French composers.

Dalila cutting Samson's hair. Jarrett Ott as Samson, Jacquelyn Stucker as Dalila, Nahuel Di Pierro as Achisch (in shadow)

The Festival d’Aix assembled a superlative cast for this unusual operatic event, singers well able to take and hold the stage, with voices accustomed to the Mozart and Rossini roles on important stages. The Americans Jarrett Ott as Samson and Jacquelyn Stucker as Dalila are refugees from the recent The Exterminating Angel at the Paris Opera, both exhibiting in these Rameau pieces an extraordinary musical intelligence that magnified their presences. Samson’s first act love affair was with the Philistine Timna, sung by French-Italian soprano Lea Desandre. She is of pure voice that beautifully melted into the Rameau ariosos. Argentine bass Nahuel di Pierro sang Achisch, the chief of the Philistines. Of fine voice he is a flashy performer who well embodied the brutal confidence of the Philistines.

Completing the cast were Julie Roset as the one winged Angel who sang the Prologue and British tenor Laurence Kilsby who sang the interpolated role of the turncoat Elon. Aixoise film and TV actress Andréa Ferréol spoke the weirdly amplified role of the mother.

Ursula Kudrna designed the costumes, lighting and video was accomplished by Bertrand Cordero. The choreography for the production's 12 dancer/acrobats was by Sommer Ulrickson.

Théâtre de L'Archevéché, Aix-en-Provence, France. July 15, 2024. All photos copyright Monika Rittershaus, courtesy of the Festival d'Aix.

Madama Butterfly at the Aix Festival

Well, why not? Why not place this iconic statement of Italian verismo in the hands of a hyper-teutonic, avant-garde (ish) stage director, adding in a new-age Italian conductor for good measure.

Not to mention a 50 year-old high-artifice diva, a heavy dose of anti-Americanism with a squawking tenor and a cold, sharp voiced baritone. The ancillary personages included an all-knowing Asian mezzo soprano, a motionless Asian bass, and two blatantly non-Asian tenors — an Italian and a Swede.

But there were six, distinctly Asian black clad supernumerary dancer types, one or some of whom stood motionless, Butoh-like, in stage pictures, when not parading with puppet cranes (the Japanese symbol of happiness, we learned from our phones at the intermission).

How did all of this work out? Well, it sort of worked out, given that Puccini’s masterwork may be indestructible.

The key to figuring it out was in the program booklet, where the stage director, Andrea Breth, herself surprised to be offered such an assignment, admits basing the production’s iconography on the arty photographs of two Austrians who had traveled to Japan in the late nineteenth century. Thus the abstracted black and white structure that served as Pinkerton’s Nagasaki minka [house], with its four downstage poles that always prevented some portion of the audience from seeing the face of whoever was singing.

Though stage director Breth insists that she avoids realism, Pinkerton was found reading a newspaper awaiting his bride, Jeffrey Epstein-like. He then took off a shoe, insisting that Suzuki wash his feet, he offered cigarettes and whiskey to Sharpless, and sang “Dovunque al mondo,” his face hidden behind a pole from my seat.

There was a platform that silently floated in from the left, crossing the stage and ending just there, forcing all entrances from the left. Butterfly slowly emerged on the moving platform, in an almost motionless tableau (she was singing), dressed in bridal white. The chorus remained hidden backstage, though a tableau of Butterfly’s relatives peeked out, the Asian supernumerary dancers in Noh theater masks.

Thus stage director Berth established Butterfly’s exotic, magical, poetic world in contrast to the crass, whiskey scented world of the Americans. Pinkerton entered into Butterfly’s world for Puccini’s magical duet “Bimba dagli occhi pieni di malia.” The new lovers remained stationary, hidden downstage in the dark while an upstage panel slowly opened, its white light intensifying as an Asian actor slowly moved the wings of a tsuru [crane] puppet, other actors following into the light, a moving tableau of flying birds.

Pole, Ermonela Jahe as Cio Cio San, Adam Smith as Pinkerton, actor with tsuru puppet, Act I

Mme. Breth’s first act was a heavy handed compendium of images, some tasteless, images she had made little effort to understand and feel, much less integrate such imagery into the verismo of Puccini’s deeply felt score. The following acts were equally troubled, if salvaged by Puccini himself and the committed performances of Butterfly and Suzuki.

It was a great pleasure to know, finally, Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho’s Butterfly (lead photo), one of her signature roles with which she has gained worldwide fame. Mme. Jaho’s voice no longer has the youthful bloom that Butterfly demands, though she sings beautifully when she allows herself the use of her mature voice. She can embody a believable Butterfly in stature and movement, her expressive face (when not hidden by a pole) easily read from the furthest reaches of a theater. Vocally she is well able to find the support needed to sing softly for extended periods, and finds Butterfly’s interpolated high C# (or maybe it’s a D) with ease. But her voice now has a dryness that rendered her second act rather colorless, though she shone in the last act’s “Tu, tu, piccolo iddio” by unleashing her mature voice.

As well, it was a great pleasure to know, finally, the mezzo-soprano Mihoko Fujimura. That she may be Japanese is irrelevant to her beautifully sung and acted performance as Suzuki. She provided a moral center for the opera for us, and offered us the emotional strength needed to accept the shattering emotions of the opera’s resolution. Mme. Fujimura is 58 years old, of a warmth of voice that exudes maturity and its attendant understanding imbued with an intensity of feeling.

British/Irish tenor Adam Smith as Pinkerton and Belgian baritone Lionel Lhote as Sharpless are excellent singers and able performers. Neither artist has the Italianate sound or beauty of voice that we associate with these roles, and that flow easily with Puccini’s score. In keeping with the casting prerogatives of the Aix Festival — sensitive, indeed subservient to the requirements of a stage director — voices and bearing were found that could bespeak the crassness of Andrea Breth’s Pinkerton and the bureaucratic coldness of her American consul. Both men obliged, fulfilling the needs of the production, exhibiting voices more suited to the central and eastern European repertory. Mr. Smith did have a couple of unfortunate squawks, from which he recovered, giving a remarkably graceful, under the circumstances, performance.

Mihoko Fujimura as Suzuki, Ermonela Jaho as Cio Cio San, Carlo Bosi as Goro, Act II

The marriage broker Gore was sung by Italian tenor Carlo Bosi. Normally the role Goro is taken by a character tenor, and given that Goro is Japanese normally he is of a slight build. Mr. Bosi is a large man with a full voice. There was no attempt to make us believe he was other than a business-like, effective marriage broker, a functionary of the crass American world. Prince Yamadori was sung by Swedish tenor Kristofer Lundin. Again no attempt was made to hide the fact that he was a tall European singer, though he at least had an abstracted headdress, indicating that he was supposed to embody a Japanese aristocrat.

Lo Zio Bonzo was ably sung by Korean bass Inho Jeong, who delivered his excommunication of Butterfly in business-like tone, standing motionless. He again appeared at the conclusion of the opera, handing Butterfly the sacrificial knife with which she slit her throat.

Conductor Daniele Rustioni is the music director of the Opéra de Lyon (a co-producer of this Butterfly), the excellent orchestra of the Opéra de Lyon was in the Aix Festival’s Archvêché theater pit. Over the years in Lyon Mo. Rustioni has shown himself receptive to understanding and supporting progressive staging concepts, as he did for this Andrea Breth production. With this orchestra that knows him well, and understands his musical being he was able to create an immediacy of sonic-scapes that gave us unusual pleasure, though perhaps confusing the back stage conductors — there were significant ensemble issues in Act I. The maestro had obvious musical sympathy with the diva, resulting in a splendid Act III.

Théâtre de l’Archvêché, Aix-en-Provence, France, July 10, 2024. All photographs copyright Ruth Walz, courtesy of the Aix Festival.

The Iphigénies at the Aix Festival

Both of them — her death in Aulide and her resurrection in Tauride, back to back, in a surreal world created by Russian stage director Dimitri Tcherniakov, rendered in overdrive within Gluck’s reformed operatic world by conductor Emanuelle Hahn and Le Concert d’Astrée.

In Aix just now the diptych was twice as long but no less shattering than the Richard Strauss Elektra — though Gluck’s voiceless Elektra had been abandoned back in Aulide.

In Tcherniakov’s Tauride a brutal Oreste, haunted by having killed his mother, was given ample rein to re-enact, repeatedly, the murder of Clytemnestra in a grandiose scene — in Tcherniakov’s surreal dream world the unities of Aristotelian tragedies do not apply. Oreste was sung by famed French Figaro, Florian Sempey, here tensely wound and in sharp voice, exploding brutally to the affections of his friend Pylade, sung with great strength and masculine warmth by French tenor Stanislaw de Barbeyrac, reacting to Oreste’s unleashed fury with equal, brutal blows.

It was very much a Straussian world. We sat at the edge of impending doom for the duration of both Iphigénies, these mythical voices crying out their torments, conductor Hahn extravagantly pulling every possible motif from the Gluck scores, the double winds and brass finding myriad colors and affections amidst the powerful swell of strings. The storm that begins Tauride was sonically absolutely terrifying, echoing to the rafters of Aix’s Grand Théâtre de Provence, the goose stepping march of the Greeks at the end of Aulide was a celebratory, musical apotheosis of war.