Some, not all, of my reviews prior to 2024

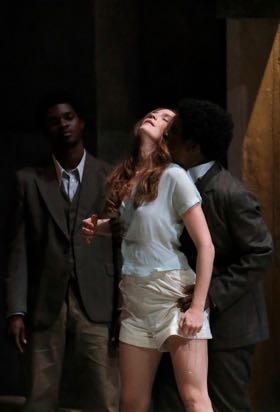

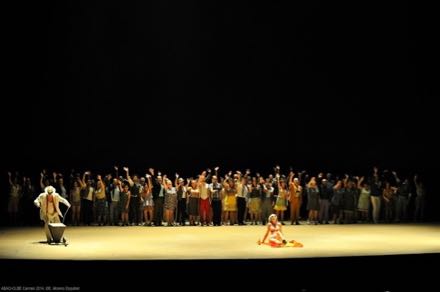

Abduction from the Seraglio in Aix-en-Provence (July 3, 2015)

Abduction from the Seraglio in Montpellier (February 5, 2013)

Abduction from the Seraglio in San Francisco (October 2009)

Adelaide di Borgogna in Pesaro (August 16, 2023)

Adriana Mater at San Francisco Symphony (June 8, 2023)

Adelaide di Borgogna and Mosé in Egitto at Pesaro (August 13/14, 2011)

Adina in Pesaro (August 20, 2018)

Aida in Berlin

Aida in San Francisco September 21, 2012

Aida in San Francisco (November 8, 2016)

Aiglon in Marseille (February 16, 2016)

Akhmatova in Paris (April 13, 2011)

Alceste, Rossignol, Don Giovanni at Aix

Alcina in Aix-en-Provence (July 4, 2015)

Alcina in Lyon

Andrea Chénier in San Francisco (September 17, 2016)

Anna Bolena in Lisbon (February 9, 2017)

Anthony and Cleopatra (Adams) at San Francisco Opera (September 23, 2022)

Apocalypse in Aix (August 20, 2021)

Arabella in San Francisco (October 16, 2018)

Ariadne auf Naxos in Bordeaux (February 23, 2011)

Ariadne auf Naxos at Aix (July 4, 2018)

Ariane et Barbe Bleu in Nice

Ariodante at the Salzburg Festival (August 22, 2017)

Ariodante at the Aix Festival (July 3, 2014)

Armida in Pesaro (August 13, 2014)

Attila in San Francisco (June 12, 2012)

Aureliano in Palmira in Pesaro (August 15, 2014)

The Avenging Angel at the Salzburg Festival (August 1, 2016)

Aureliano di Palmira in Pesaro (August 15, 2023)

Ballets Russes at the Aix Festival (July 10, 2023)

Un ballo in maschera in San Francisco (October 7, 2014)

Un ballo in maschera at the Chorégies d'Orange (August 6, 2013)

Barbe-Bleue in Lyon (June 23, 2019)

The Barber of Seville by San Francisco Opera (April 27, 2021)

Il barbiere di Siviglia in San Francisco (December 1, 2015)

Il barbiere di Siviglia in Pesaro (August 14, 2014)

The Barber of Seville in Pesaro (August 19, 2018)

The Barber of Seville in Montpellier

The Barber of Seville in San Francisco (November 13, 2013)

Il barbiere di Siviglia in Marseille (February 9, 2018)

The Bassarids in Salzburg (August 16, 2018)

La Belle Hélène in Marseille

Benjamin, Dernière Nuit in Lyon (March 18, 2016)

Billy Budd in Los Angeles (March 16, 2014)

Belshazzar in Aix (July 23, 2008)

Benvenuto Cellini in Rome (March 29, 2016)

Billy Budd in Madrid (February 12, 2017)

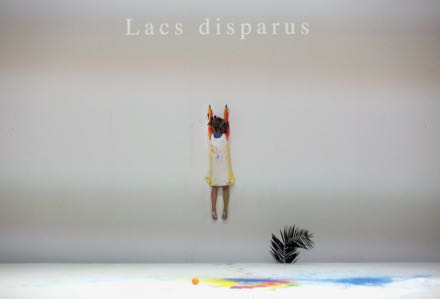

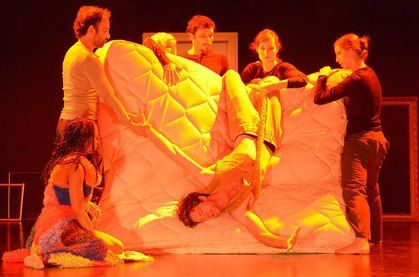

Blank Out at the Aix Festival (July 14, 2019)

Bluebeard’s Castle in Los Angeles (November 9, 2014)

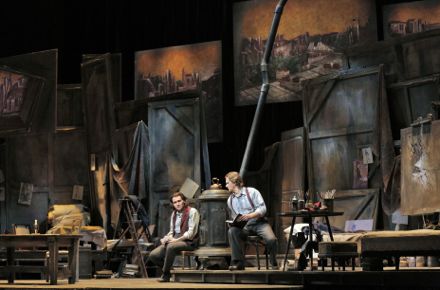

La bohème at FIFOE (September 1, 2023)

La bohéme in San Francisco (June 15, 2017)

La bohème in San Francisco (November 19 and November 20, 2014)

La Bohème in Toulon (December 29, 2011)

La Bohème in Genoa (January 5, 2012)

La Bohème in Marseille (January 3, 2012)

La Bohème at Torre del Lago (August 12, 2011)

La Bohème in San Francisco (November, 2008)

La Bohème in Toulon, Marseille and Genoa (December 2011/January 2012)

La Bohème at San Francisco's Ft. Mason Drive-in Theater (Nov 12, 2020)

Bonjour M. Gauguin in Berkeley (El Cerrito) (April 6, 2013)

Boris Godunov in Marseille (February 21, 2017)

Boris Godunov in San Francisco (November 4, 2008)

Boris Godunov at the San Francisco Symphony (June 14, 2018)

Boulevard Solitude in Barcelona

The Brahms Third in San Francisco (Berkeley) (May 17, 2013)

Callirhoé in Montpellier

I Capuleti e i Montecchi in San Francisco (September 29, 2012)

Carmen at FIFOE (September 2, 2023)

Carmen in Marseille (February 21, 2023)

Carmen at the Opéra Bastille (January 28, 2023)

I Capuleti ed i Montecchi in Rome (February 16, 2020)

Carmen at the Festival d'Aix (July 4, 2017)

Carmen at Orange (July 11, 2015)

Carmen in Bilbao (February 18, 2014)

Carmen in San Francisco (November 12, 2011)

Carmen in San Francisco (May 28 and June 1, 2016)

Carmen in San Francisco (June 11, 2019)

Carrie The Musical in San Francisco (October 5, 2013)

Cavalleria rusticana and I pagliacci in Marseille (February 3, 2011)

Cavalleria rusticana and I pagliacci in San Francisco (September 28, 2018)

La cenerentola in Lyon (December 15, 2017)

Cendrillon in Marseille

La cenerentola in San Francisco (November 13, 2014)

La Cenerentola, Sigismondo, Demetrio e Polibio at Pesaro

Le Cercle de Craie in Lyon (January 20, 2018)

The Charterhouse of Parma in Marseille (February 12, 2012)

Ciro in Babilonia in Pesaro (2012)

La Clemenza di Tito, La Traviata, Le Nez in Aix-en-Provence (July, 2011)

Cléopâtre in Marseille (June 23, 2013)

Le Comte Ory in Pesaro (August 16, 2022)

Combattimento in Aix (July 16, 2021

)

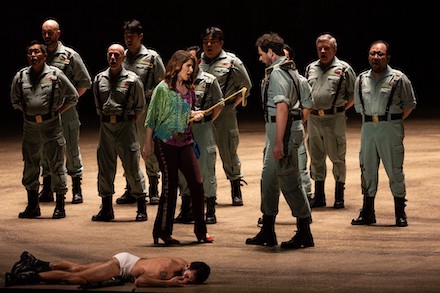

Die Eroberung von Mexico at the Salzburg Festival (August 1, 2015)

The Conquest of Mexico at the Salzburg Festival (August 1, 2015)

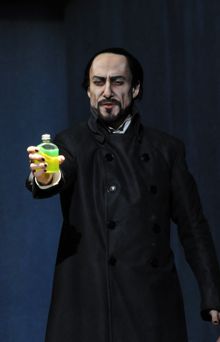

Les Contes d'Hoffmann in Lyon (December 26, 2013)

Les Contes d'Hoffmann in San Francisco (June 5, 2013)

Les Contes d'Hoffmann in Torino (February 2, 2009)

Coeur de Chien in Lyon (January 30, 2014)

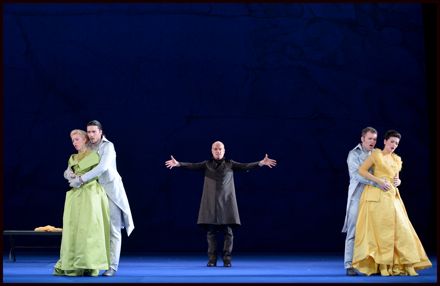

Cosi fan tutte at the Aix Festival (July 17, 2023)

Cosi fan tutte in San Franciscoe (November 21, 2021)

Cosi fan tutte in Montpellier (January 9, 2014)

Cosi fan tutte in San Francisco (June 9, 2013)

Cosi fan tutte and Zaide in Aix (July 16, 2008)

Cosi fan tutte at the Aix Festival (June 30, 2016)

Cosi fan tutte at the Salzburg Festival (August 2, 2016)

Cosi fan tutte and Eugene Onegin in Los Angeles (October 1-2, 2011)

Cyrano de Bergerac in San Francisco

David et Jonathas in Aix (July 11, 2012)

The Death of Klinghoffer at the ENO (February 12, 2012)

Demetrio e Polibio, La Cenerentola, Sigismondo at Pesaro

Dialogues of the Carmelites at San Francisco Opera (October 18, 2022)

Dialogues des Carmélites in Toulon (January 29, 2013)

Dialogues des Carmélites in Marseille

Dido and Aeneas in Los Angeles (November 9, 2014)

Dido and Aeneas in Marseille

Dido and Aeneas in Toulon (April 18, 2011)

Dido and Aeneas in Aix (July 7, 2018)

Dido and Aeneas in Lyon (March 29, 2019)

Dolores Claiborne in San Francisco (September 18, 2013)

Don Carlo in Marseille (June 17, 2017)

Don Carlo in San Francisco (June 15, 2016)

Don Carlos in Barcelona

Don Carlos in Lyon (March 16, 2018)

Don Giovanni in San Francisco (June 8, 2017)

Don Giovanni at the Festival d'Aix (July 5, 2017)

Don Giovanni in Carmel Valley (September 22, 2013)

Don Giovanni, Alceste, Rossignol at Aix

Don Giovanni at the Aix Festival (July 18, 2013)

Don Giovanni in Genoa

Don Giovanni in Montpellier

Don Giovanni in Marseille (April 12, 2011)

Don Giovanni in Paris (June 22, 2019)

Don Giovanni at San Francisco Opera (June 10, 2022)

Don Pasquale in Weimar (January 31, 2009)

Don Pasquale in San Francisco (October 4, 2016)

La donna del lago in Pesaro (August 11, 2016)

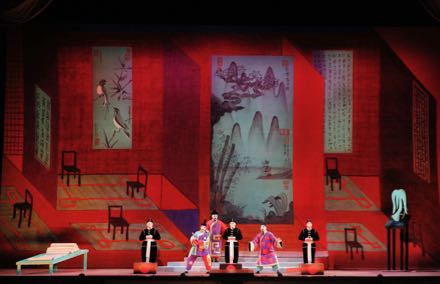

Dream of the Red Chamber in San Francisco (September 18, 2016)

Duke Bluebeard's Castle in Salzburg (August 6, 2022)

Edoardo e Cristina in Pesaro (August 14, 2023)

Eight at the Aix Festival (July 11, 2019)

Elektra at the Salzburg Festival (August 28, 2021)

Elektra at the Aix Festival (July 19, 2013)

Elektra in San Francisco (September 13, 2017)

Elektra in Lyon (March 17, 2017)

Elettra a Marsiglia (10 febbraio 2013)

Elektra in Marseille (February 10, 2013)

Elena at the Aix Festival (July 17, 2013)

Elisabetta, regina d'Ingliterra in Pesaro (August 2021)

L'elisir d'amore at San Francisco Opera (November 19, 2023)

L'elisir d'amore in Marseille (January 2, 2015)

L'elisir d'amore in Monte-Carlo (February 26, 2014)

L'elisir d'amore in San Francisco(November, 2008)

The Enchantress in Lyon (March 21, 2019)

L'Enfant et les Sortileges in Monte-Carlo (January 25, 2012)

Die Entführung aus dem Serail in San Francisco (October 2009)

Die Entführung aus dem Serail in Montpellier (February 5, 2013)

Ercole Amante in Toulon

Erismena at the Festival d'Aix (July 7, 2017)

Ermione and Maometto II in Pesaro August 13, 2008

Eugene Onegin at San Francisco Opera (September 28, 2022)

Eugene Onegin in Montpellier (January 17, 2014)

Eugene Onegin in Marseille

(February 13, 2020)

Eugene Onegin and Mazeppa in Lyon

Eugene Onegin and Cosi fan tutte in Los Angeles (October 1-2, 2011)

The Fall of the House of Usher in San Francisco (December 10, 2015)

Falstaff at the Salzburg Festival (August 23, 2023)

Falstaff in Aix-en-Provence (July 6, 2021)

Falstaff in Genoa (January 28, 2017)

Falstaff in Los Angeles (November 24, 2013)

Falstaff in San Francisco (October 8, 2013)

Faust in Orange (August 2, 2008)

La fanciulla del West in San Francisco

Faust in Marseille (February 16, 2019)

Faust in San Francisco

Scenes from Faust in Parma

La Favorite in Toulouse (February 16, 2014)

Fedora in Genoa (March 25, 2015)

Fidelio in San Francisco (Oct 20, 2021)

The Fiery Angel at Aix (July 5, 2018)

Der Fliegende Holländer in San Francisco (October 22, 2013)

Die Fliegende Hollander in Dresden (March 2, 2019)

A Florentine Tragedy and I pagliacci in Monaco (February 25, 2015)

A Florentine Tragedy and The Secret of Susanna in Montpellier

Die Frau ohne Schatten at San Francisco Opera (June 10, 2023)

Der Freischutz in Toulon (January 30, 2011)

From the House of the Dead in Lyon (January 23, 2019)

La gazza ladra in Pesaro (August 13, 2015)

La gazzetta in Pesaro (August 14, 2015)

Gianni Schicchi in Arezzo (August 2, 2018)

Giasone in Geneva (February 1, 2017)

Girls of the Golden West in San Francisco (November 29, 2017)

Gloria in Cagliari (February 15, 2023)

The Golden Cockerel in Aix September 21, 2021

Götterdammerung at San Francisco Opera (June 17, 2018)

Götterdämmerung in Palermo (February 2, 2016)

The Greek Passion at the Salzburg Festival (August 22, 2023)

Guillaume Tell in Monaco (January 25, 2015)

Guillaume Tell in Pesaro (August 14, 2013)

Guillaume Tell in Palermo (January 23, 2018)

Hamlet in Paris (March 21, 2023)

Heart of a Soldier in San Francisco (September 13, 2011)

The House Taken Over at the Aix Festival (July 23, 2013)

Idomeneo at the Aix Festival (July 8, 2022)

Idomeneo in Lyon (February 2, 2015)

Idomeneo in Montpellier (January 4, 2015)

L'incoronazione di Poppea at the Aix Festival (July 18, 2022)

L'incoronazione di Poppea in Lyon (March 16, 2017)

L'incoronazione di Poppea in Edinburgh

The Indian Queen at ENO (March 9, 2015)

L'inganno felice in Pesaro (August 15, 2015)

Innocence in Aix (October 2021)

Intolleranza 1960 in Salzburg (August 26, 2021)

Iolanthe in Aix-en-Provence (July 17, 2015)

Iphigénie en Tauride in Geneva (February 4, 2015)

Irrelohe in Lyon (March 17, 2022)

L'italiana in Algeri in Pesaro (August 13, 2013)

L'Italiana in Algeri in Marseille (January 2, 2013)

It's a Wonderful Life in San Francisco (November 20, 2018)

Jacob Lenz at the Aix Festival July 14, 2019)

Jeanne d'Arc au bucher in Lyon (January 31, 2017)

Jenufa in Toulon

Jenufa in San Francisco (June 14, 2016)

Jerry Springer, The Opera in San Francisco

La Juive in Lyon (March 19, 2016)

Kat'a Kabanova in Rome (January 21, 2022)

Kat'a Kabanova in Salzburg (August 7, 2022)

Kat'a Kabanova in Toulon (January 25, 2015)

Kalîla wa Dimna at the Aix Festival (July 17, 2016)

King Arthur in Montpellier (July 17, 2009)

Lady MacBeth of Mtsensk at the Salzburg Festival (August 21, 2017)

Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in Lyon (January 27, 2016)

Lear at the Salzburg Festival (August 23, 2017)

Die Liebe der Danae at the Salzburg Festival (August 5, 2016)

The Lighthouse at San Francisco's Opera Parallèle (May 1, 2016)

Lohengrin at San Francisco Opera (October 18, 2023)

Lohengrin in Los Angeles

Lohengrin in San Francisco (October 23, 2012)

Lohengrin at Bayreuth (August 11, 2018)

Lucia di Lammermoor in Los Angeles (March 15, 2014)

Lucia di Lammermoor in San Francisco (October 13, 2015)

Lucia di Lammermoor in Marseille (February 6, 2014)

Lucio Silla in Nice

Lucrezia Borgia in San Francisco (September 26, 2011)

Lucrezia Borgia in Toulouse (February 3, 2019)

Luisa Miller in San Francisco (September 16, 2015)

Macbeth at the Salzburg Festival (August 24, 2023)

Macbeth in Lyon (March 15, 2018)

Madama Butterfly at San Francisco Opera (June 6, 2023)

Madama Butterfly in San Francisco (June 15, 2014)

Madama Butterfly in San Francisco (November cast)

Madama Butterfly in San Francisco

Madama Butterfly in Genoa

Madama Butterfly in San Francisco (November 12, 2016)

The Makropulos Case in San Francisco

The Makropulos Case in San Francisco (October 18, 2016)

The Magic Flute at the Aix Festival (July 2, 2014)

The Magic Flute in San Francisco (October 27, 2015)

Die Zauberflöte in Los Angeles (November 23, 2013)

The Magic Flute in San Francisco (June 13, 2012)

Mahagonny in San Francisco (April 26, 2014)

Les Mamelles de Tirésias in San Francisco (April 26, 2014)

Les Mamelles de Tirésias et La Voix Humaine in Toulon

Manon in San Francisco (November 7, 2017)

Manon Lescaut in Lyon

Manon Lescaut in Genoa

Manon Lescaut at the Salzburg Festival (August 4, 2016)

Maometto II and Ermione in Pesaro August 2008

Marius et Fanny in Marseille

The Mastersingers of Nurenburg at ENO (March 7, 2015)

I masnadieri in Rome (January 21, 2018)

Die Meistersinger at Bayreuth (August 12, 2018)

Mathilda di Shaban in Pesaro (2012)

Mazeppa and Eugene Onegin in Lyon

Mazeppa in Monte-Carlo (February 28, 2012)

Mefistofele in San Francisco (September 14, 2013)

Mefistofele in Montpellier

Mefistofele at the Chorégies d'Orange (July 9, 2018)

Die Meistersinger in San Francisco (November 24, 2015)

A Midsummer Night's Dream in Aix-en-Provence (July 16, 2015)

Les Milles Endormis at the Aix Festival (July 14, 2019)

Mireille in Toulon

Moby Dick in San Francisco (October 10, 2012)

Moīse et Pharoan at the Aix Festival (July 12, 2022)

Moīse et Pharoan in Pesaro (August, 2021)

Monster of the Labyrinth at the Aix Festival (July 9, 2015)

Monteverdi Madrigals in Edinburgh

Mosé in Egitto and Adelaide di Borgogna at Pesaro (August 13/14, 2011)

The Mozart Requiem at the Aix Festival (July 5, 2019)

Nabucco in Verona (August 17, 2023)

Nabucco at Orange (July 9, 2014)

Nabucco in Toulon

La Navarraise in Monte-Carlo (January 25, 2012)

Le Nez, La Clemenza di Tito, La Traviata in Aix-en-Provence (July, 2011)

Norma in San Francisco (September 10, 2014)

Norma at the Salzburg Festival (July 31, 2015)

Nixon in China in San Francisco (June 8, 2012)

Le nozze di Figaro in Aix (August 13/14, 2021)

Le nozze di Figaro in Los Angeles

Le nozze di Figaro in San Francisco

Le nozze di Figaro in Paris (May 17, 2011)

Les Noces de Figaro in Aix (July 5, 2012)

Les Noces de Figaro in Montpellier (June 26, 2012)

Le nozze di Figaro in Genoa

L'occasione fa il ladro in Pesaro (August 15, 2013)

Oedipus Rex and Symphony of Psalms at the Aix Festival (July 17, 2016)

Oedipus Rex at San Francisco Symphony (June 12, 2022)

Omar at San Francisco Opera (November 7, 2023)

L'Orfeo at Aix

Orfeo & Majnun in Aix (July 8, 2018)

Orlando in San Francisco (June 15, 2019)

Orphée aux Enfers in Montpellier

Orfeo ed Euridice at San Francisco Opera (November 15, 2022)

Orfeo ed Euridice in Rome (March 27, 2019)

Orfeo ed Euridice in Rome (2019?)

Orphée et Eurydice in Montpellier

Orphée et Eurydice in Toulon

The Outcast in Hamburg (March 4, 2019)

Otello at Los Angeles Opera (May 20, 2023)

Otello in Pesaro (August 14, 2022)

Otello in Genoa (January 3, 2014)

Otello in Montpellier

Otello in San Francisco (November 2009)

Otello in Zurich (January 8, 2012)

Parsifal at Bayreuth (August 19, 2023)

Parsifal in Toulousee (February 4, 2020)

Parsifal in Palermo (January 28, 2020)

Parsifal in Nice

Parsifal in Brussels (February 8, 2011)

Peer Gynt in Genoa

Pelleas et Melisande in Montpellier (March 13, 2022)

Pelleas et Melisande in Montpellier

Pelleas et Melisande in Nice (January 17, 2013)

Pelleas et Melisande in Nice

Pelleas et Melisande at the Aix Festival (July 4, 2016)

La Périchole in Marseille (March 8, 2020)

Persephone in Aix-en-Provence (July 17, 2015)

Peter Grimes at the Palais Garnier (January 29, 2023)

Peter Grimes in Nice (January 24, 2015)

Phaedra and Dido and Aeneas in Marseille

Picture a Day Like This at the Aix Festival (July 15, 2023)

La Pieta in Romee (March 28, 2019)

La pietra del paragone at the Rossini Festival, Pesaro (August 17, 2017)

Pinocchio at the Festival d'Aix (July, 2017)

Pique Dame in Lyon

Pique Dammen in Salzburg (August 14, 2018)

Platée at the Palais Garnier (June 21, 2022)

Porgy and Bess in San Francisco (November 20, 2013)

Porgy and Bess in San Francisco (June 2009)

Le Prophèt at the Aix Festival (July 15, 2023)

A Quiet Place at the Palais Garnier (March 21, 2022)

Radamisto in Palo Alto (April 24, 2022)

The Rake's Progress at the Festival d'Aix (July 8, 2017)

Das Rheingold at San Francisco Opera (June 12, 2018)

Das Reingold in San Francisco

"Resurrection" at the Aix Festival (July 10, 2022)

The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs at San Francisco Opera (October 3, 2023)

Ricciardo e Zoraide in Pesaro (August 18, 2018)

Rigoletto in Lyon (March 18, 2022)

Rigoletto in San Francisco (June 6, 2017)

Rigoletto in Los Angeles

Rigoletto in San Francisco (September 19, 2012)

Rigoletto at the Aix Festival (July 23, 2013)

Das Ring des Nibelungen in Los Angeles

Das Ring des Nibelungen in San Francisco

Das Ring der Nibelungen in San Francisco (June 12 - 17, 2018)

The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny at the Aix Festival (July 9, 2019)

Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria in San Francisco (April 2, 2009)

Roberto Devereux in Genoa (February 26, 2016)

Roberto Devereux in San Francisco (September 27, 2018)

Romeo et Juliette in Toulon

Roméo et Juliette in Toulon

Roméo et Juliette in Los Angeles (November 9, 2011)

Rossignol, Alceste, Don Giovanni at Aix

Rusalka in Monte-Carlo (January 29, 2014)

Rusalka in Madrid (November 25, 2020)

Rusalka in San Francisco (June 16, 2019)

The Saint of Bleecker Street in Marseille

Salome at the Aix Festival (July 5, 2022)

Salome in Montpellier

Salome (Mariotte) in Montpellier

Salome in San Francisco (November 2009)

Salome in Salzburg (August 13, 2018)

Salustia in Montpellier July 28, 2008

Sampiero Corsu in Marseille

Samson et Dalila at the Metropolitan Opera (March 29, 2019)

Scenes from Faust in Parma

The Secret of Susanna and A Florentine Tragedy in Montpellier

Siegfried at San Francisco Opera (June 15, 2018)

Séméle in Montpellier

Seven Stones in Aix (July 8, 2018)

Show Boat in San Francisco (June 3, 2014)

La Siège de Corinthe at the Rossini Festival, Pesaro (August 16, 2017)

Sigismondo, La Cenerentola, Demetrio e Polibio at Pesaro

Il signor Bruschino in Pesaro (August 2021)

Il signor Bruschino in Pesaro (2012)

Simon Boccanegra in Salzburg (August 15, 2019)

Sorbet, Sorbet in Carnoules

Susannah in San Francisco (September 12, 2014)

Svadba in Aix-en-Provence (July 8, 2015)

Svadba in San Francisco (April 8, 2016)

Symphony of Psalms at the Aix Festival (July 17, 2016)

Symphony of Psalms at the San Francisco Symphony (June 12, 2022)

Sweeney Todd in San Francisco (September 23, 2015)

The Tales of Hoffmann see Les Contes d'Hoffmann

Tannhauser at the Met (NYC) (October 15, 2015)

Tannshauser in Dresden (March 1,2019)

De Temporum Fine Comoedia in Salzburg (August 6, 2022)

The Tender Land in Lyon (February 1, 2014)

Teseo in Nice

Thaïs in Los Angeles (June 1, 2014)

The Three Penny Opera at the Aix Festival (July 7, 2023)

Torvaldo e Dorliska at the Rossini Festival, Pesaro (August 18, 2017)

Tosca at Opera San Jose (March 26, 2023)

Tosca in San Francisco (November 4, 2014)

Tosca in Marseille (March 18, 2015)

Tosca at Orange

Tosca in Rome

Tosca in San Francisco (November, 2009)

Tosca Postcript in San Francisco (November 21, 2012)

Tosca II in San Francisco (November 16, 2012)

Tosca I in San Francisco (November 15, 2012)

Tosca at the Aix Festival (July 6, 2019)

Tosca At the Metropolitan Opera (March 28, 2019)

Tosca in San Francisco (October 11, 2018)

Die Tote Stadt in San Francisco (2008)

Trauernacht in Lyon (March 19, 2022)

Trauernacht at the Aix Festival (July 16, 2014)

La Traviata at San Francisco Opera (November 16, 2022)

La traviata in San Francisco (September 26, 2017)

La Traviata in San Francisco (June 11, 2014)

La traviata in Marseille (June 21, 2014)

La Traviata, La Clemenza di Tito, Le Nez in Aix-en-Provence (July, 2011)

Il trionfo et il disinganno at the Aix Festival (July 6, 2016)

Tristan und Isolde in Toulouse (March 1, 2023)

Tristan und Isolde at the Opéra Bastille (January 26, 2023)

Tristan und Isolde in Bayreuth (August 12, 2022)

Tristan et Isolde in Ai (February 5, 2021)

Tristan ed Isolde in Bologna (April 13, 2020)

Tristan und Isolde in Lyon (March 18, 2017)

Tristan et Isolde in Toulouse (February 1, 2015)

Tristan und Isolde in Genoa

Tristan und Isolde in Montpellier

Il trittico in San Francisco

Il trittico in Lyon (February 8, 2012)

Les Troyens in San Francisco (June 7 and June 12, 2015)

Les Troyens in Marseille (July 15, 2013)

Il trovatore at San Francisco Opera (September 18, 2023)

Le Trouvère at the Opéra Bastille (January 27, 2023)

Il trovatore in Toulon

Il trovatore in San Francisco (September 11, 2009)

Il trovatore at Orange

Turandot in Verona (August 13, 2022)

Turandot in San Francisco (September 12, 2017)

Turandot in San Francisco (September 17, 2011)

Turandot in San Francisco (November 18, 2011)

Turandot in San Francisco (November 6, 2017)

Il turco in Italia at the Aix Festival (July 19, 2014)

Il Turco in Italia in Los Angeles

Il turco in Italia in Pesaro (August 12, 2016)

The Turn of the Screw in Los Angeles

Two Women in San Francisco (June 13, 2015)

El Ultimo Sueño de Frida y Diego at San Francisco Opera (June 13, 2023)

Vanessa in Berkeley (September 21, 2013)

Les Vêpres Siciliennes in Palermo (January 23, 2022)

Verdi Messa da requiem in Naples (February 28 and March 1, 2013)

The Verdi Requiem at San Francisco Opera

The Verdi Requiem at the Chorégies d'Orange (July 16, 2016)

Il viaggio, Dante at the Aix Festival (July 15, 2022)

Il viaggio a Reims in Pesaro (August, 2022)

La Voix Humaine et Les Mamelles de Tirésias in Toulon

Die Walkûre in Marseille (February 11, 2022)

Die Walküre in San Francisco

Die Walküre in Toulouse (February 6, 2018)

Die Walküre at San Francisco Opera (June 13, 2018)

Werther in Monte-Carlo (February 20, 2022)

Werther in Marseille (March 1, 2022)

Werther in Lyon (February 4, 2011)

Werther in San Francisco

West Side Story in San Jose (April 21, 2022)

William Tell in Pesaro (August 14, 2013)

Winterreise at the Aix Festival (July 12, 2014)

It's a Wonderful Life in San Francisco (November 20, 2018)

Wozzeck at the Aix Festival (July 18, 2023)

Wozzeck at the Salzburg Festival (August 24, 2017)

Wozzeck in Nice

Wozzeck in Barcelona

Wozzeck at UC Berkeley (November 9, 2012)

Written on Skin in Aix (July 7, 2012)

Xerxes in San Francisco (November 16, 2011)

Zaide and Cosi fan tutte in Aix (July 16, 2008)

Die Zauberflöte see Magic Flute

The Elixir of Love at San Francisco Opera

That's L’elisir d’amore, Donizetti’s bel canto gem, dolled up somewhere on the Italian riviera by the same team that set San Francisco Opera’s 2012 Lohengrin in a Soviet era, bookless Romanian library near a bus station.

So it was the piazza in front of the Hotel Adina, the proprietress of which, Donizetti’s heroine Adina, was so busy reading the Tristan myth and brushing off her suitors that she exhibited no proprietary interest whatsoever in her namesake inn where Nemorino is the only waiter.

Additional conceits included Donizetti’s swaggering soldier sergeant Belcore transformed into a policeman, though he seemed more a sailor in casual whites, who made his entrance on a Vespa motor scooter (electrified to-be-sure — no real, ugly diesel fumes or scary screeching (vespa means wasp). Plus the everything elixir salesperson, Dulcamara, arrived in a hot air balloon, a French Revolutionary touch (there was a pause in the performance so this entrance could be set up).

Opening night was a Sunday matinee, and the audience ate it up.

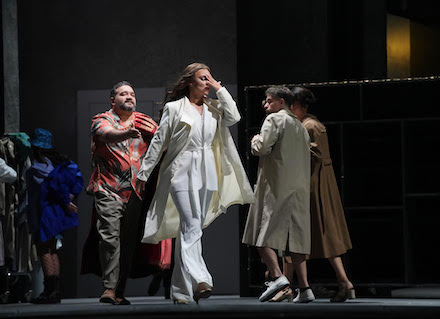

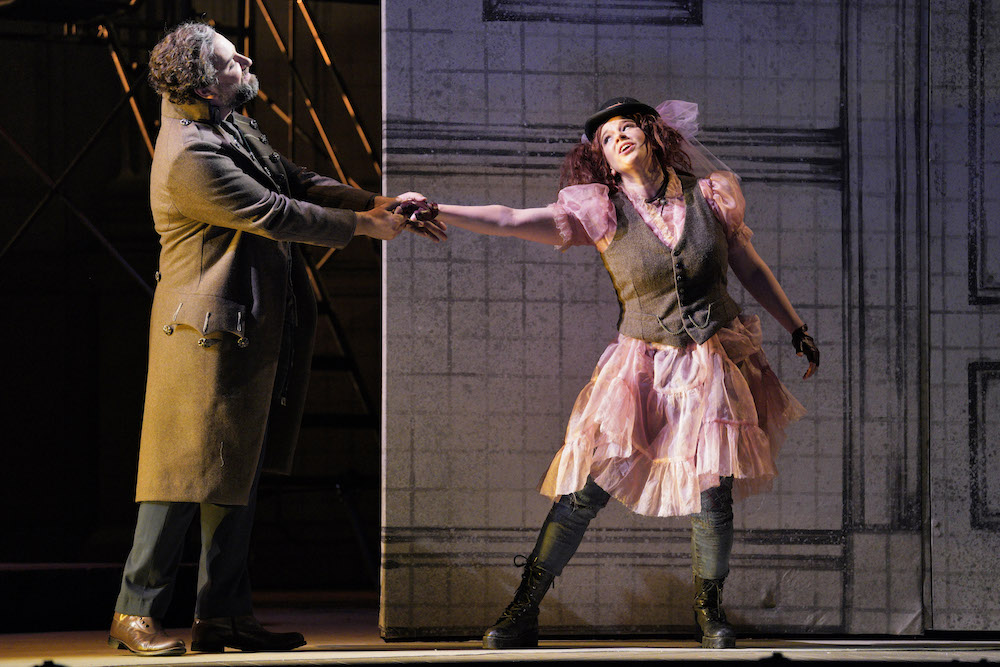

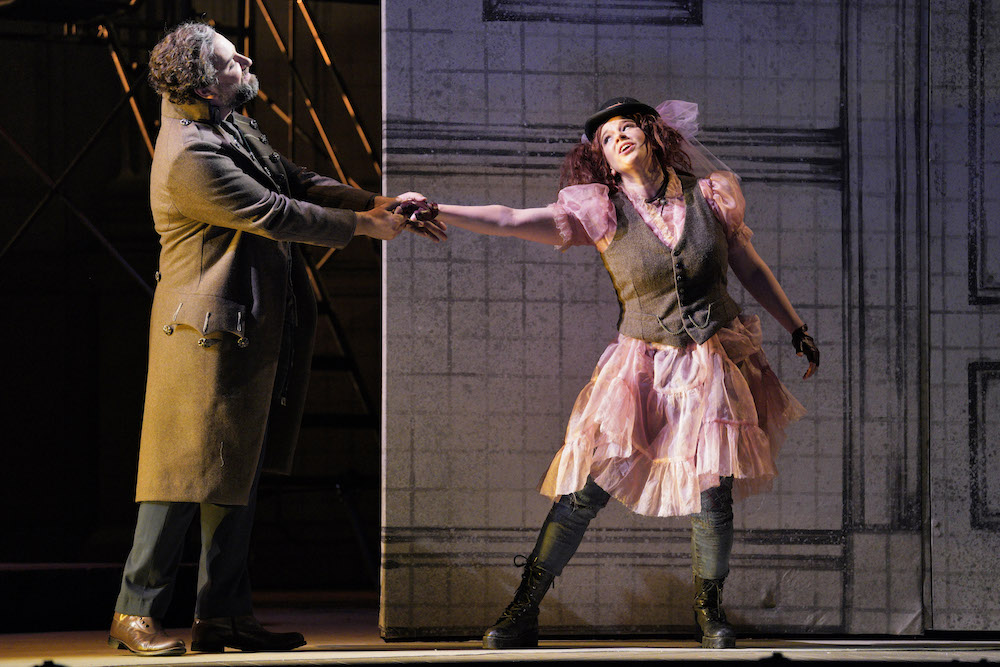

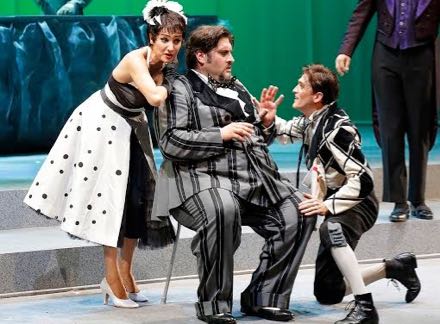

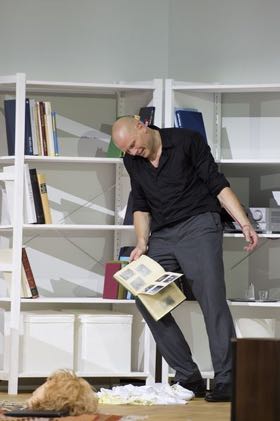

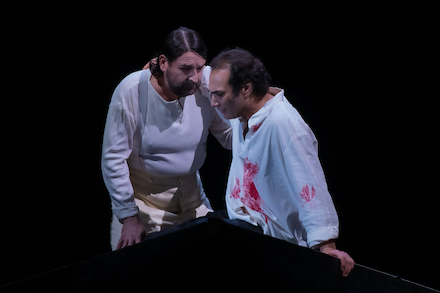

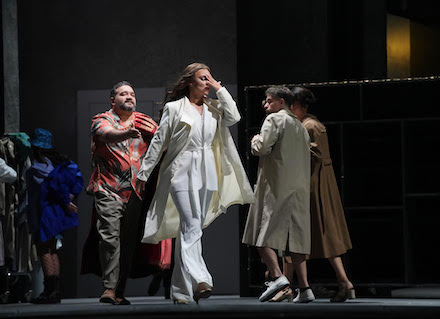

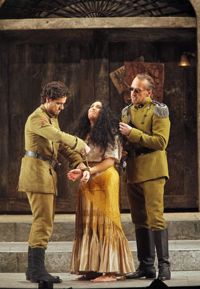

Slávka Zámečníková as Adina, David Bizic as Belcore

Slávka Zámečníková as Adina, David Bizic as Belcore

This was the 2016 production from Britain’s Opera North (based in Leeds), though it was originally conceived back in 2001. It comes to San Francisco via Lyric Opera of Chicago where it played in 2021. It seemed a bit small for the War Memorial stage. The original British team was on hand — stage director Daniel Slater and production designer Robert Innes Hopkins (designer of SFO’s new, milquetoast Tosca), and lighting designer Simon Mills.

The production’s many pantomime moments (group choreography and slapstick humor) made it seem so very Brighton Beach.

Not to be outdone by Caruso’s Nemorino La Scala role debut (“Una furtiva lagrima” was repeated three times) San Francisco Opera fielded New Zealand tenor Pene Pati, a former Adler with a big career, whose “Una furtiva lagrima” had to wait through an eternity of silence, save for the electron screeching of someone’s hearing aid low battery warning, a pause imposed by the conductor until the screech was quelled. Mr. Pati is a very effective Nemorino, a fine comic actor, his vocal presentation is clean and pure, his persona is a pure Pavarotti imitation, lacking only the white hanky for his extravagant bows.

Adina was sung by Austrian soprano Slávka Zámečníková, a lithesome presence with the requisite charm for this Donizetti role. Mlle. Zamecnikova has a silvery thread of voice, though of obvious amplitude to be heard in the important theaters she inhabits. Well able to vocally negotiate the fioratura of Donizetti’s bel canto, she does not bring a heft of voice or personality to make such virtuosity sound important. I was left unimpressed and unfulfilled.

French baritone David Bizic created a fresh and charming, young Belcore. With a finely wrought, healthy young voice he made this role far more sympathetic than simply a stock buffo presentation. In the end, out maneuvered by Nemorino, he eloped with Gianetta on his electric Vespa. Gianetta was sung by current Adler Fellow Arianna Rodriguez who faded into the scenery, though some good high notes came through from time to time.

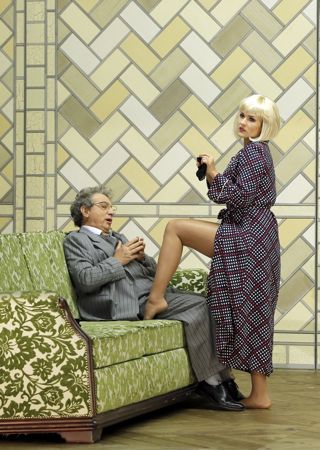

Renato Girolami as Dulcamara, Pene Pati as Nemorino

Renato Girolami as Dulcamara, Pene Pati as Nemorino

Italian buffo Renato Girolami as Dulcamara was the star of the production — well, along with Pene Pati’s oversized Nemorino. Mr. Girolami brought sophisticated, big house know-how to this archetypal buffo role. He found a warmth of tone and persona for this Dulcamara that made him a benevolent deus ex machina (the hot air balloon) rather than the usual shyster.

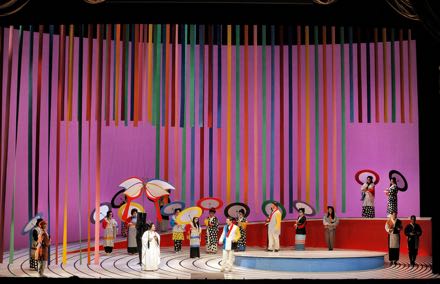

The San Francisco Opera Chorus surely had great fun in preparing and performing this tour de force for opera chorus. There was great detailing in the chorus roles (see lead photo), many individual characters emerged with contagious energy. Ramón Tebar conducted the San Francisco Opera Orchestra with magisterial assurance, bringing welcome care to making Donizetti’s magnificent score work into this production.

The Elixir of Love concludes the San Francisco fall season of five operas. None of the productions originated in San Francisco.

War Memorial Opera House, November 19, 2023

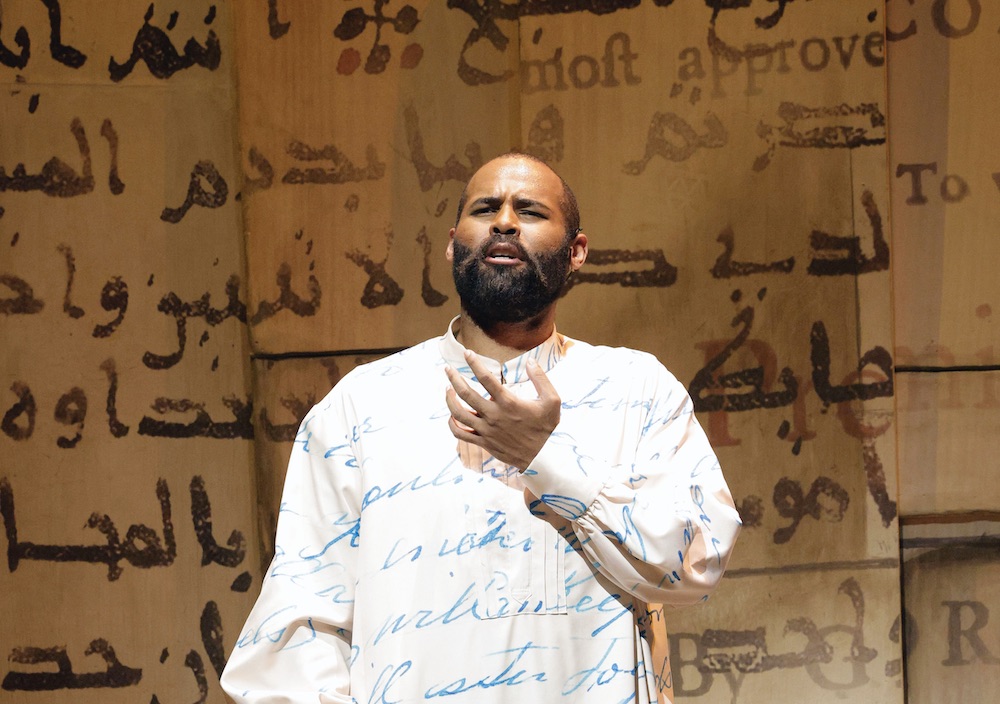

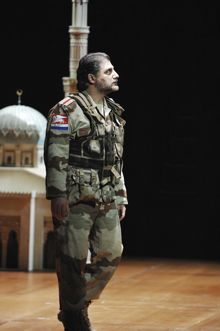

Omar at San Francisco Opera

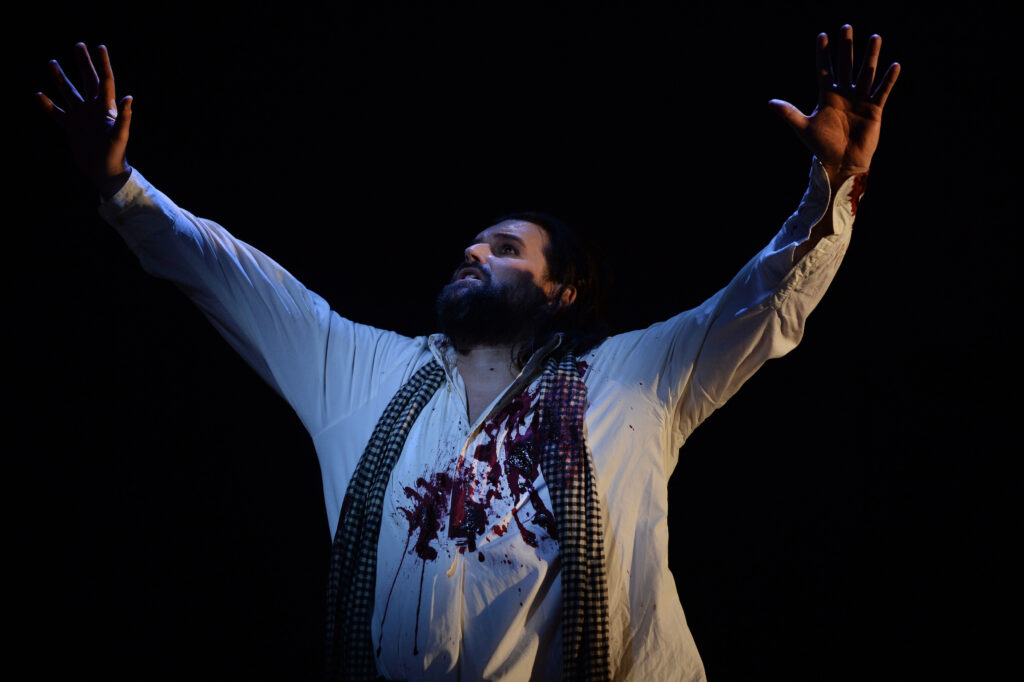

The black man Omar Ibn Said was forcibly brought from sub-Saharan Africa to South Carolina in 1807. He was sold, becoming an indentured person for life (d. 1863). Omar the opera delves into the fascinating complexities of this life.

Omar was a 30’s-some years-old Islamic scholar at the time of his abduction [Islam had come into the western sub-Sahara in the sixth century CE]. As a Qur’an scholar he had learned to read and write, thus his enlightened American owner gave him a Christian bible in Arabic to hasten his inevitable conversion. Omar, a noted personality in his time (he was dubbed an Arabian prince), created brief phrases in Arabic to assuage the Southern gentry’s taste for exotic shapes, and as well left an array of short documents in Arabic. One is titled “I cannot write my life.”

These texts have proven very difficult to decipher (casual grammar, weird syntax, etc.), though recent scholarship claims to have done so. While some brief texts are embedded within the opera’s libretto, Omar the opera creates a framework for Omar’s Allah to become enmeshed within South Carolina’s Jesus.

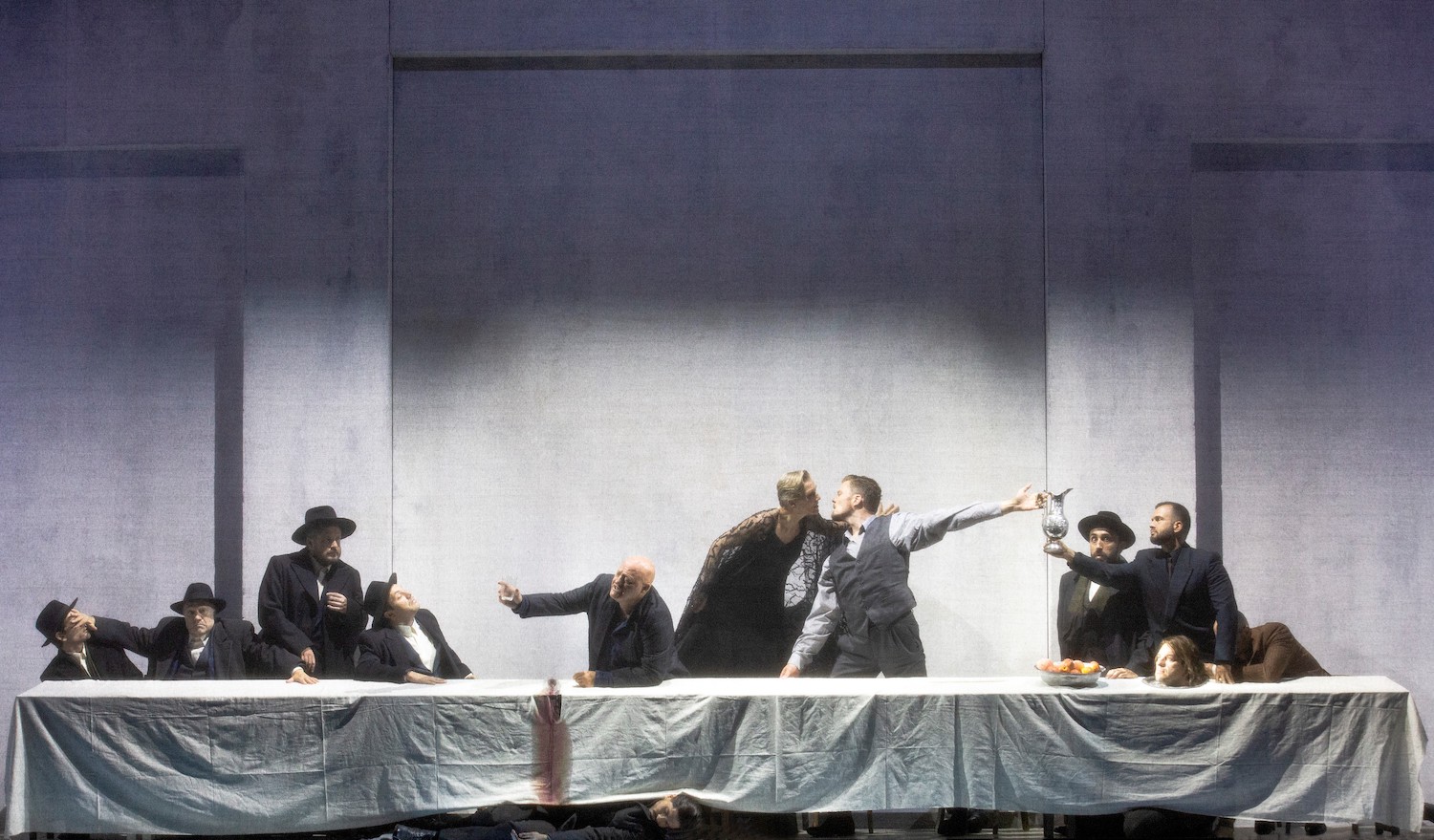

There is no underlying operatic tension (will he or even can he change his faith?), thus the opera is more an oratorio — a series of tableaux that imagine and elaborate key moments of Omar’s spiritual life. He has two guides in the opera’s libretto — the first is his mother who tells him that there is no direct path through life, that there may well be sharp bends. The second is the slave girl Julie who encourages him to escape his initial bondage and come to Fayetteville where he joins her among persons indentured to the Owens family.

Omar is not an operatic tale of two slaves falling in love. Julie is but Omar’s talisman. She brings him to a magical Fayetteville [NC] where Eliza, the daughter of the Owens family patriarch Jim, in her innocence, recognizes his spirituality. Jim asks Omar to write in Arabic script “the Lord is my shepherd” — the 23rd Psalm, though Omar writes “I want to go home!” Jim is none the wiser.

The opera then embarks on an extended meditation of the 23rd Psalm — “[the Lord] maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters,” etcetera, and concludes with a huge finale of the three principal voices (Omar, Julie, the Mother) joined with the sizable ensemble of black singers to intone, hugely, Omar’s invocation that they love and respect their roots, their ancestral home, Allah be praised.

It is unfortunate that this religious oratorio arrives at this particular moment in human history, when religions, any and all, are held in particularly low esteem. At the same time it is exciting for opera, and particularly opera in America, to discover this rich trove of stories that cry out to be told in this sumptuous, multifaceted art form.

Like the late 16th century Italian staged pastorals there were dance scenes. The whirling blue dancer often appeared as Omar’s sufistic self. The choreographer was Klara Benn.

The libretto is quite brilliant, evoking the 16th century pastoral poetry that fostered the origins of opera. Much use is made of rhyming, that both recalls the Italian pastoral poets (Tasso, Guarini, et al) and the musicality associated with the inflections of the early forms of African American Language [AAL]. There is a canny respect for the formalities of opera that have developed over the last few hundred years — well placed arias, songs, plus a number of duets of very satisfying dramatic intensity. And, of course, there is the magnificent Mozartian finale the ends the opera.

This excellent production of Omar originated at the Charleston’s Spoleto Festival in June, 2022 traveling to LA Opera that fall, continuing to Boston Lyric Opera this past May. It is staged by Kaneza Schaal, a veteran of high art theater in the U.S., upholding that reputation with this spare, Broadway style staging. Design credits are varied, certainly the look can be attributed to Christopher Myers, a New York based interdisciplinary artist rooted in storytelling and artmaking (tapestry, etc.), thus explaining the wonderful “primitive art” slave ship back drop in the first act and the magnificent rope construction that was the huge tree of life that looms in the opera’s finale. Scenery design is ascribed to Amy Rubin, lighted by Pablo Santiago.

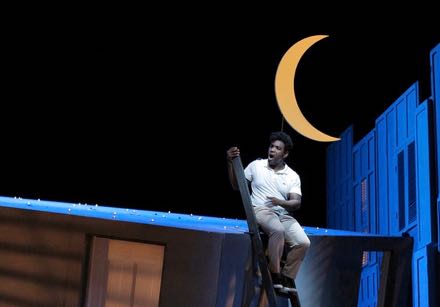

The costumers, April M. Hickman and Micheline Russell-Brown, supported stage director Schaal’s nifty framing of the opera — at the beginning singer Jamez McCorkle, very much a black prince, comes from the auditorium onto the stage in an “Alice in Chains” t-shirt (a Seattle based rock group) and white sneakers where he becomes the enrobed Omar. At the conclusion of the opera, an instrumental postlude allows him to return to his contemporary, non-ceremonial status, descending, transformed, again among us.

The musical score was created by both the librettist, folk singer Rhiannon Giddens, and film composer Michael Abels. It is richly colored and exceedingly descriptive, and is of little interest. The Omar score took the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for music. The great accomplishment of the score’s creators was its formal structure, presumably the collective efforts of the librettist, composers and stage director. No dramaturg is credited.

Tenor Jamez McCorkle was superbly voiced as Omar, in a focused, ringing tenor. Of wonderful, refined singing as well was the Jim Owens of Canadian baritone Daniel Okulitch, this quality performance added significant and much needed dignity to the Jesus camp. Character tenor Barry Banks as the auctioneer had the dubious distinction of singing the word “nigger.” Though soprano Brittany Renee as Julie fulfilled the role’s vocal needs, neither she nor mezzo soprano Taylor Raven as the insufficiently voiced mother achieved the electric presences needed to galvanize these two essential roles. Mezzo soprano Laura Krumm as Jim Owen’s daughter Eliza, did find the magic of her role, the third of Omar’s muses.

Assembling a cast for Omar is much like the daunting task of assembling a cast for Porgy and Bess. The smaller roles and the larger ensembles were all effectively realized. The San Francisco Opera Orchestra, conducted by John Kennedy, was double winds and trumpets, triple horns and trombones, piano and harp, and full strings. Plus a panoply of African drums tapped by three European percussionists.

War Memorial Opera House, November 7, 2023

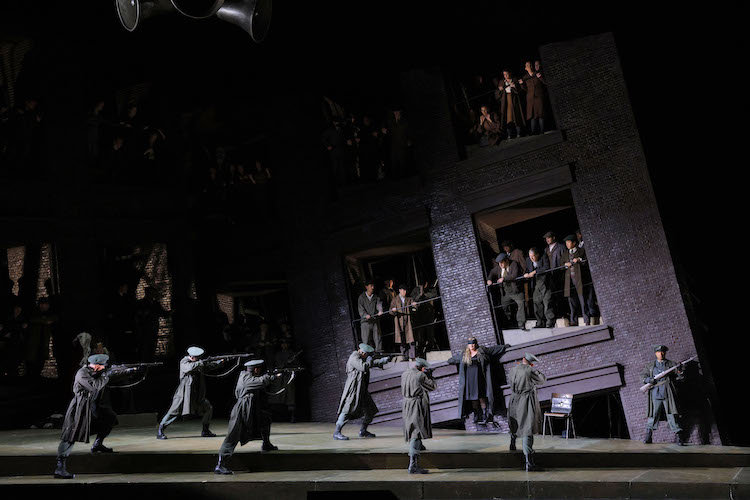

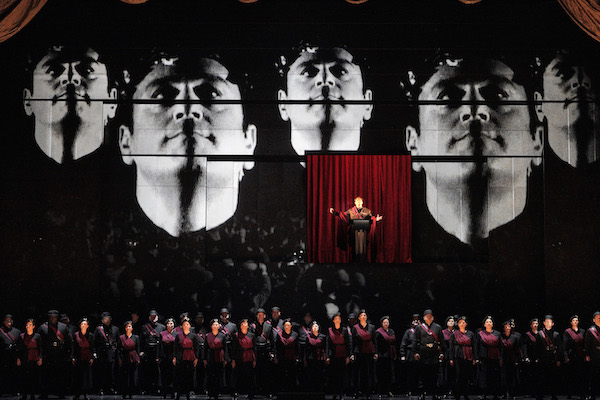

Lohengrin at San Francisco Opera

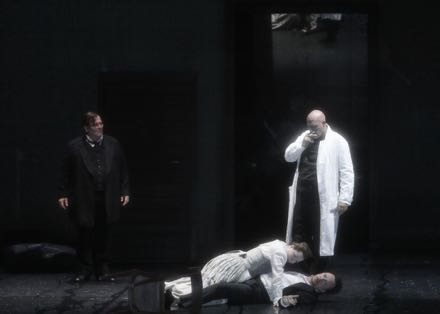

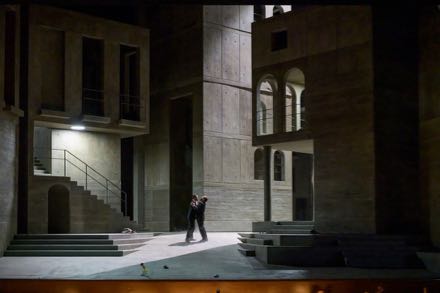

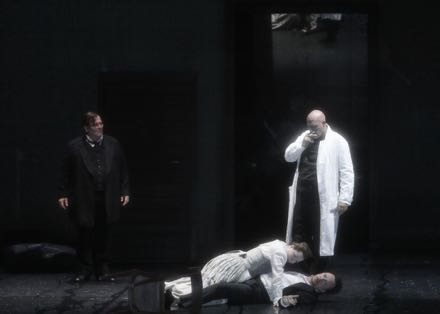

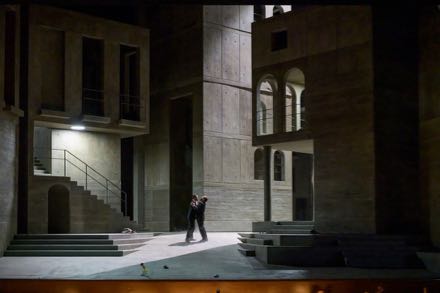

This is the excellent David Alden 2018 production from Covent Garden. Here is how it fared at the War Memorial Opera House.

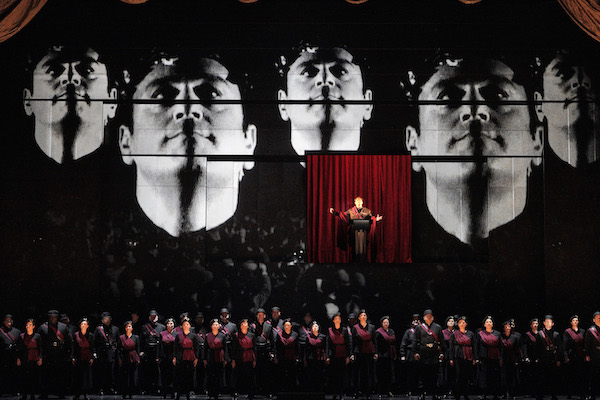

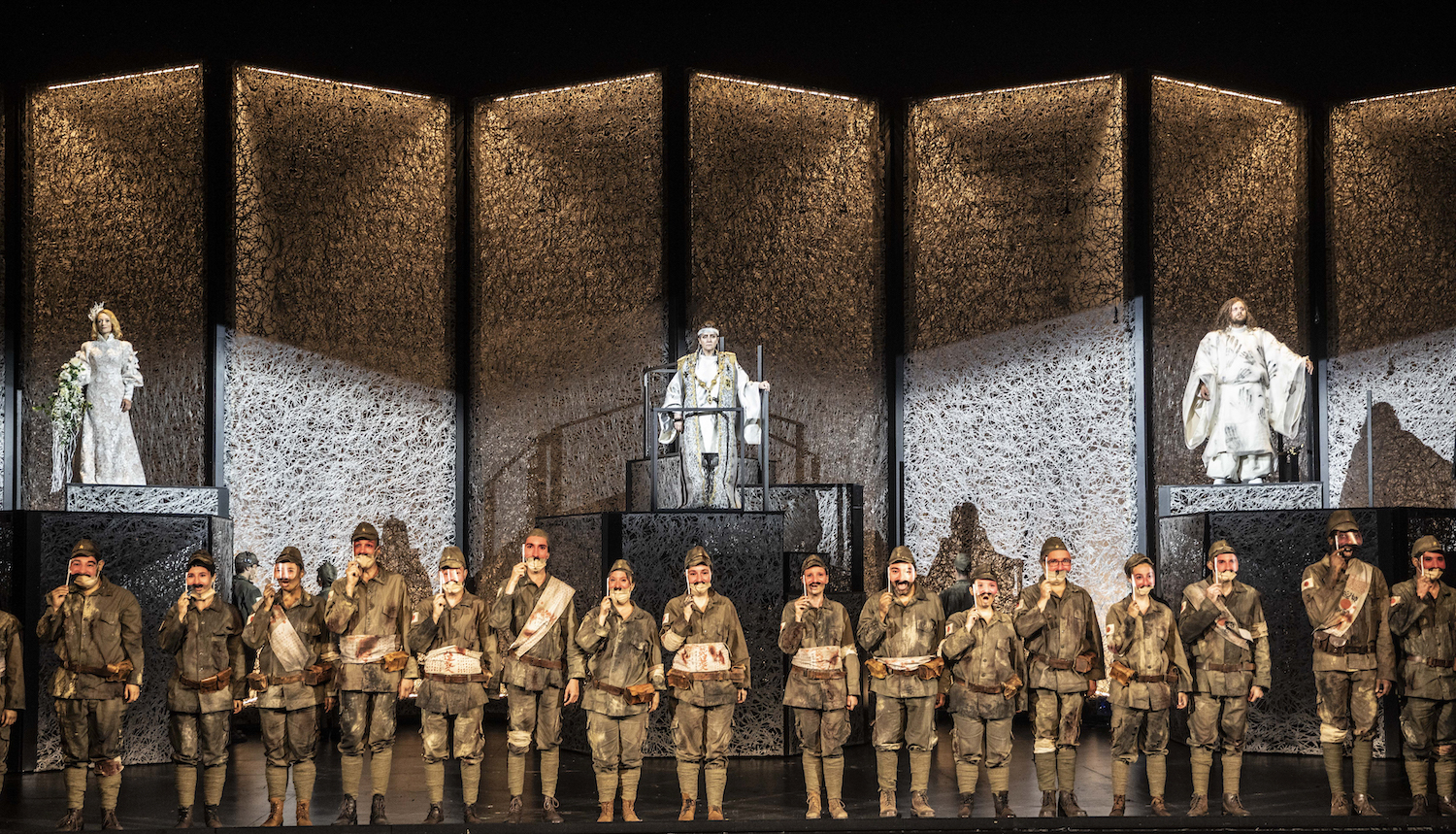

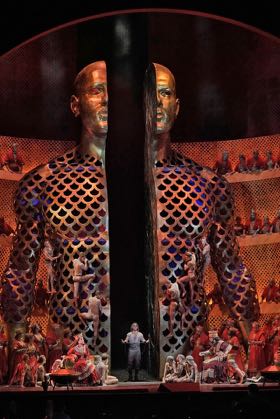

It fit like a glove due to strong casting, and the rigid musical control of conductor Eun Sun Kim, and the sheer brilliance of the production — its magnificent architecture and the consummate telling of Wagner’s first go at his last opera (Lohengrin is Parsifal’s son).

In the Wagner canon Lohengrin follows Tannhäuser and Der Fliegende Holländer (Rienzi will be admitted in 2026 when Bayreuth, overruling Wagner, stages it). The newly minted “gesamtkunstwerk” Lohengrin composer is in his richer dramatic phase, his stories/poems less philosophically refined, therefore allowing considerable interpretive latitude.

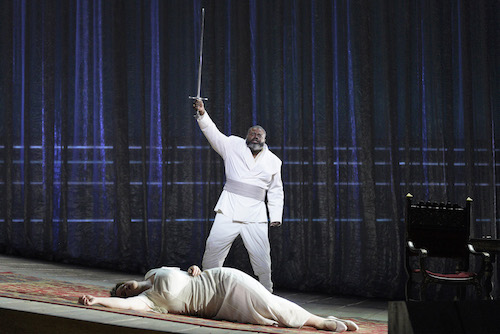

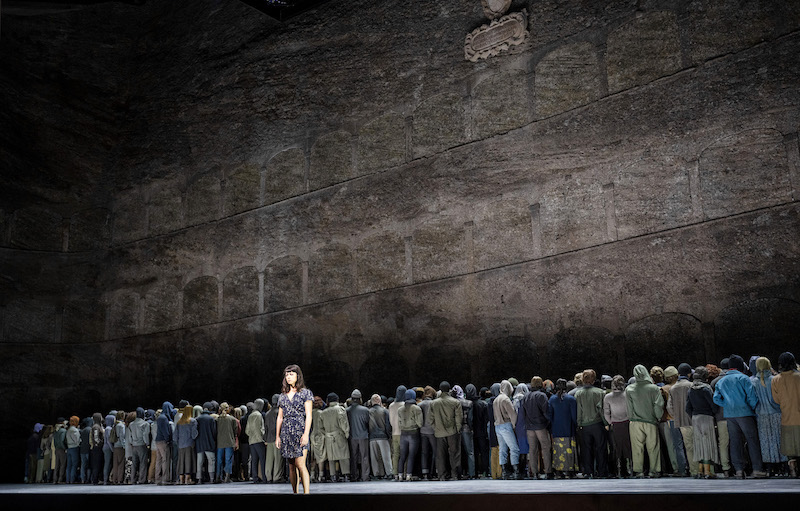

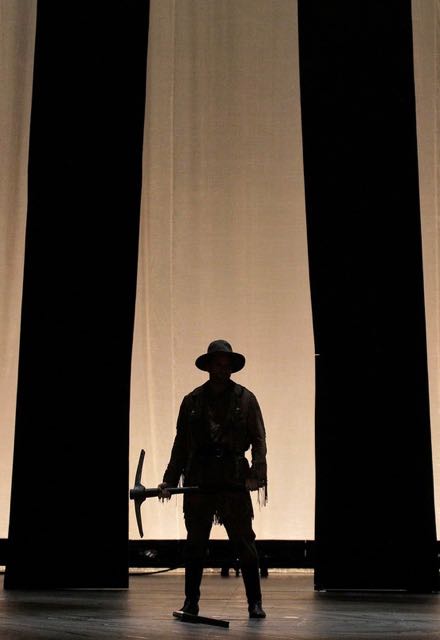

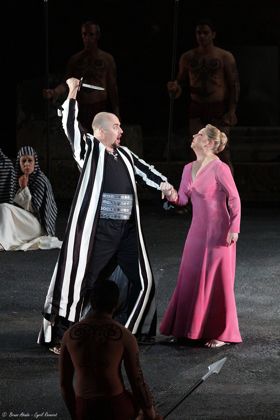

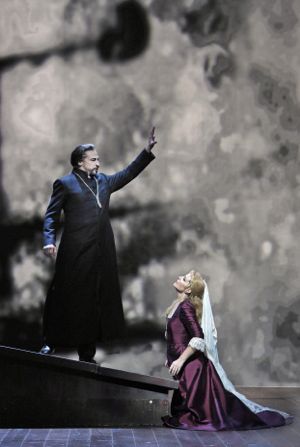

David Alden seizes this weakness to commit Wagner to a supposed divine purpose, one that overrides human desires, demanding their sacrifice, and advocates the use of human might to achieve a perceived higher purpose. The Alden Lohengrin tragedy went far beyond the sacrifice of Lohengrin and Elsa (lead photo), and therefore humanity, to the triumph of might.

Julie Adams as Elsa, Act 1

Julie Adams as Elsa, Act 1

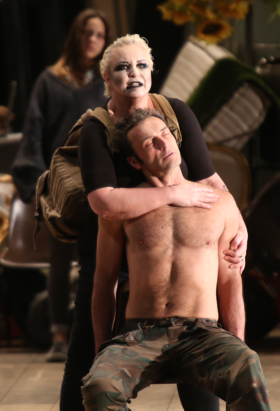

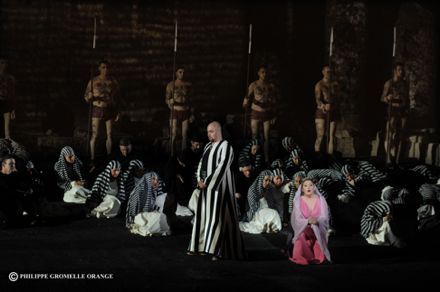

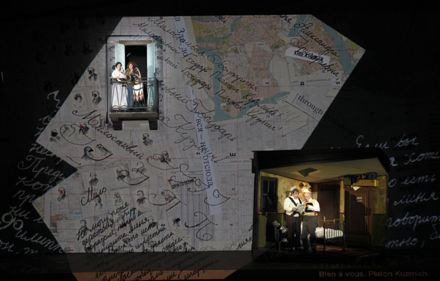

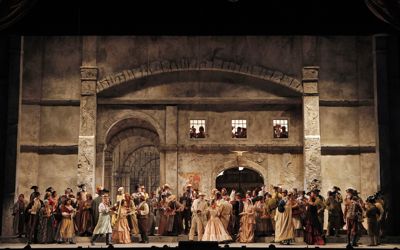

Set designer Paul Steinberg effected this suffocating world with massively oversized architectural elements seen from a dizzying perspective, elements that moved to assume evermore overpowering stances. Stage director David Alden effected human desires in the dark, animal like coupling of Telramund and Ortrud in the second act, and the white purity of the unconsummated marriage bed in the third act, both acts manifesting the futility of human feeling.

This Lohengrin ended with the swan child Gottfried raising his sword to the massive sonic strokes of Wagner’s closure. A brutal ending.

Conductor Eun Sun Kim established firm musical control from the first whispered sounds of the prelude. The War Memorial Opera House does not offer the magical acoustic of Bayreuth, thus the musical unfolding of the Wagner poem was procedural, save the magical moments when this conductor unlocked all fetters to the lyricism of Wagner’s poetic development, notably first in Elsa’s dream, then in Ortrud’s diatribes, in Telramund’s sniveling, and finally in Lohengrin’s pompous revelations. As is her wont the maestra made the big moments huge. And hugely satisfying.

Much like the musical telling, the narrative unfolding of this made-over teutonic tale was procedural. Given that the set established a Nazi era, western world, Alden was able to settle into each of the opera’s moments without adding fascistic editorial. Lohengrin and Elsa, Telramund and Ortrud remained human, feeling creatures — if on superhuman scale. Their situations and movements were sometimes worldly, sometimes symbolic, and always painstakingly structured dramatically.

Like the music, the narrative was an agglomeration of carefully formed episodes. Though Lohengrin is of extended length, dramatically unfolding moment by moment by moment, Alden and the maestra maintained a steady, even dramatic tension. We always cared about the purity of love (and its purpose) of Elsa and Lohengrin, and were repulsed by the nefarious intentions of Ortrud and Telramund. It was a world of black and white, both colors of divine motivation, Wagner tells us. In the Alden production it was not for us to judge (and our sympathies did wander from time to time to Ortrud and Telramund), only to recognize that it would be the sword that would prevail.

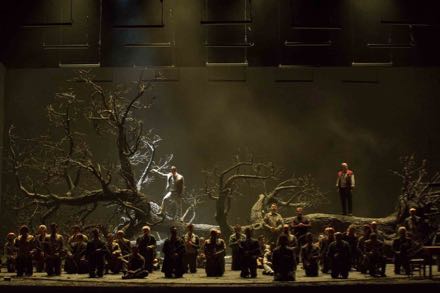

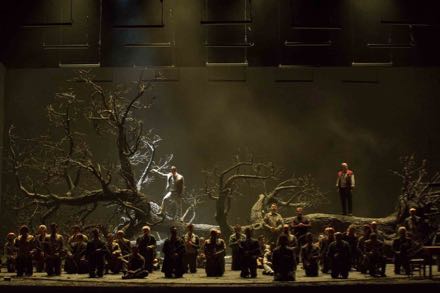

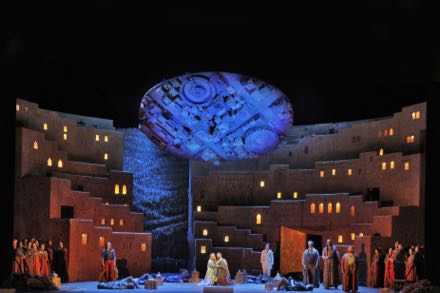

Final scene of the David Alden production of Lohengrin, set design by Paul Steinberg

Final scene of the David Alden production of Lohengrin, set design by Paul Steinberg

In a pre-curtain speech San Francisco Opera General Director Matthew Shilvock felt the need to offer comfort for our eventual discomfort with the politics of this Lohengrin. I confess that I soon saw Joe Biden as the ancient King Heinrich and Lohengrin as Donald Trump and Ortrud and Telramund as intruders who slipped through our southern border — hardly the intention of this London based director. Mr. Shilvock, less specifically, invoked Israel and Ukraine. For Wagner, as interpreted by Alden, it was purely philosophic.

It was a cast of like voiced singers — vibrant, young sounding, beautiful voices that gave immediate life, depth and urgency to Wagner’s poem, enhancing David Alden’s disturbing revelations of its inflammable subtexts.

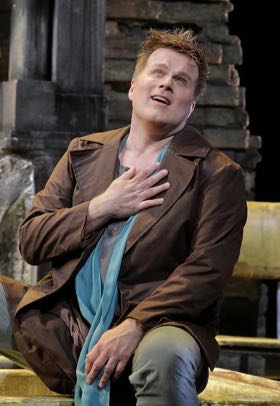

Former Merola participant, tenor Simon O’Neill, now 52 years old, is a Lohengrin of youthful heroic voice (jugendlicherheldentenor), perfectly suited to be the son of Parsifal. His voice exudes the purity, clarity and force needed for a knight imbued with divine purpose. He gracefully overwhelmed Telramund in their first act battle, returned for the magnificent, second act Rossini-like finale, and mesmerized us with his third act confession, laid out in unflagging, huge volume.

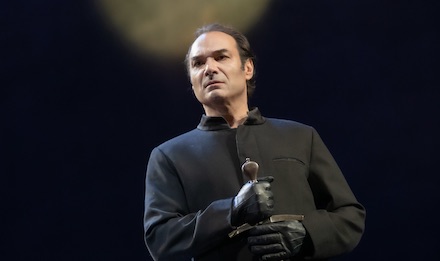

Brian Mulligan as Telramund, Act 1

Brian Mulligan as Telramund, Act 1

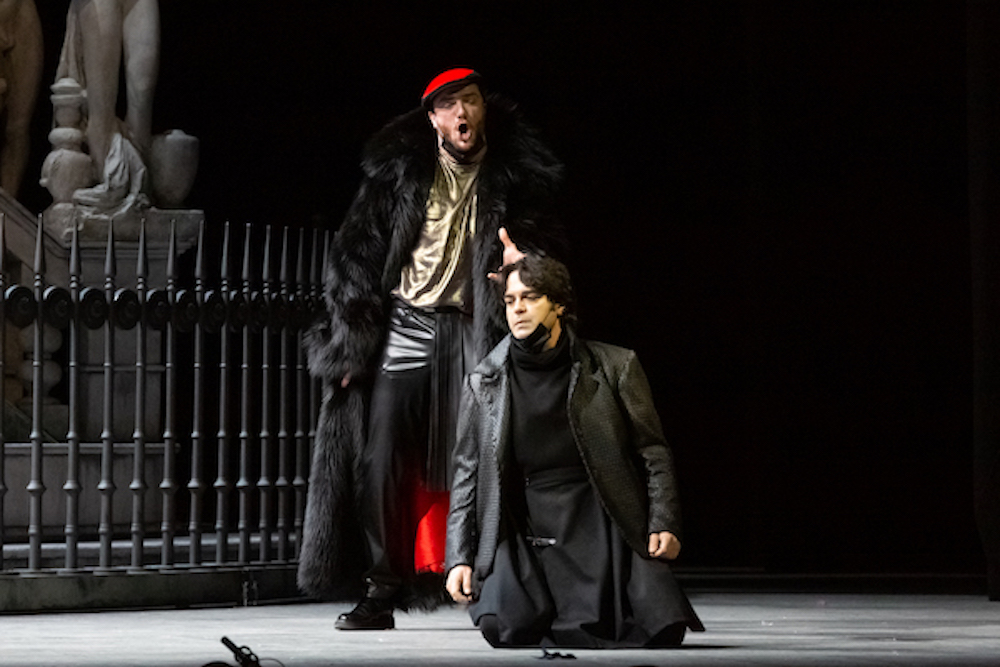

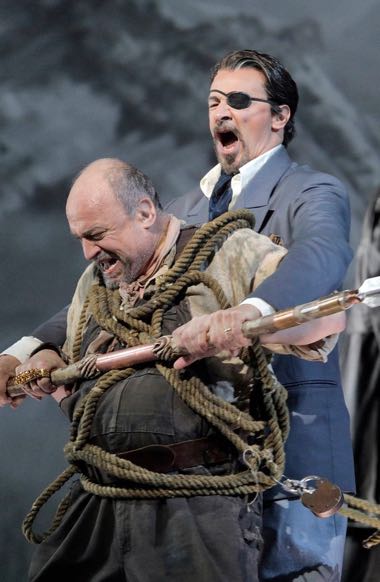

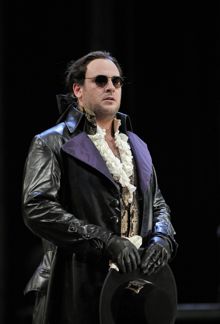

Telramund was sung by baritone Brian Mulligan in his role debut. Once San Francisco Opera’s go-to baritone for whatever role you can think of. Mr. Mulligan has found his place as a heroic baritone, hints of which first appeared when he sang the King’s Herald in San Francisco Opera’s 2012 Lohengrin (and as well in the Met’s unfortunate production last year). His golden, bell like tone made his strutting as the first act pretender and his second act manipulation by Ortrud even more pathetic.

The King’s Herald was sung by Thomas Lehman. Fitted with a mechanical prosthetic leg, he brought huge presence to this career building role. Mr. Lehman is of fine, heroic voice, that enabled him to create a personage who accepted force and violence at any cost. King Heinrich was sung by Kristinn Sigmundsson, a role he sang as well in the 2012 production. He projected abject weakness and vulnerability in his ever more declined vocal estate.

Elsa was sung by former San Francisco Opera Adler Julie Adams. Mlle. Adams has all the vocal qualities of a young dramatic soprano, a voice of weight and purity that uniquely qualifies her for the first three Wagner heroines (though she doesn’t list Senta in her repertory). Moreover she is able to physically project the youthful, innocent fortitude of these heroines. Her spectacular delivery of her dream in Act 1 planted her heroic vision in our hearts, only to have her shatter it with the aggressive demands of her marriage bed.

Ortrud was sung by Romanian mezzo soprano Judit Kutasi. Like all Ortruds, everywhere, she got the biggest ovation (all were huge), and that’s because she has the loudest music, and has the most defined and pleasurably complex character. Mme. Kutasi brought gusto and great pride to this Ortrud, in forceful, dark and solid voice. She masterfully manipulated both Elsa and Telramund, satisfying our urges to shatter the fantasies and aspirations of these two victims.

Finally the role of the citizens of Brabant was played by the San Francisco Opera Chorus. It is one of the biggest and most difficult chorus roles in the repertory. Along with the San Francisco Opera’s orchestra, its chorus is world class. The chorus role was executed with absolute precision within complex choreography, in exquisite voice.

It was an evening of high level and important art at San Francisco Opera.

War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco. October 18, 2023

The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs at San Francisco Opera

Is it man pitted against machines, or is it man sacrificed to machine? Or is it mankind sacrificed to machines. Sitting in the War Memorial Opera House for Mason Bates’ The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs was being caught at ground zero.

It wasn’t about a man named Steve Jobs, a high profile, tech giant. It was about making a machine or machines that consumed this man. The cancer that took the storied entrepreneur’s life was his pursuit of perfecting and selling the machines that he (and his colleague Steve Wozniak) created — the machines that have come to dominate or, may we say, consume our lives.

Machines that by now, 2023, have come to make human intelligence obsolete, and to boot, have made San Francisco into a ghost city.

The final scene (of 18) of the opera is the memorial service for the Apple founder. His wife Laurene offers a cold-blooded assessment of the memorialists, noting that they cannot wait to leave so that they may check their phones.

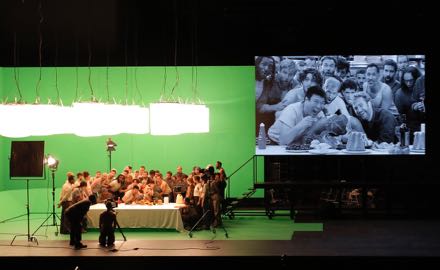

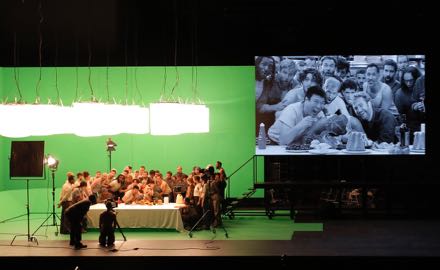

The opera was created soon after Steve Jobs’ 2011 death, and in the wake of the two immediate biographies. Its premiere was at Santa Fe Opera in 2017, and since it has traveled to Seattle, Austin, Kansas City, Atlanta, Calgary and Salt Lake City. Originally scheduled for San Francisco back in 2020, the opera, co-commissioned by Santa Fe, Seattle and San Francisco, is at last on the War Memorial stage, no worse for wear, indeed certainly well honed to a fine level of perfection.

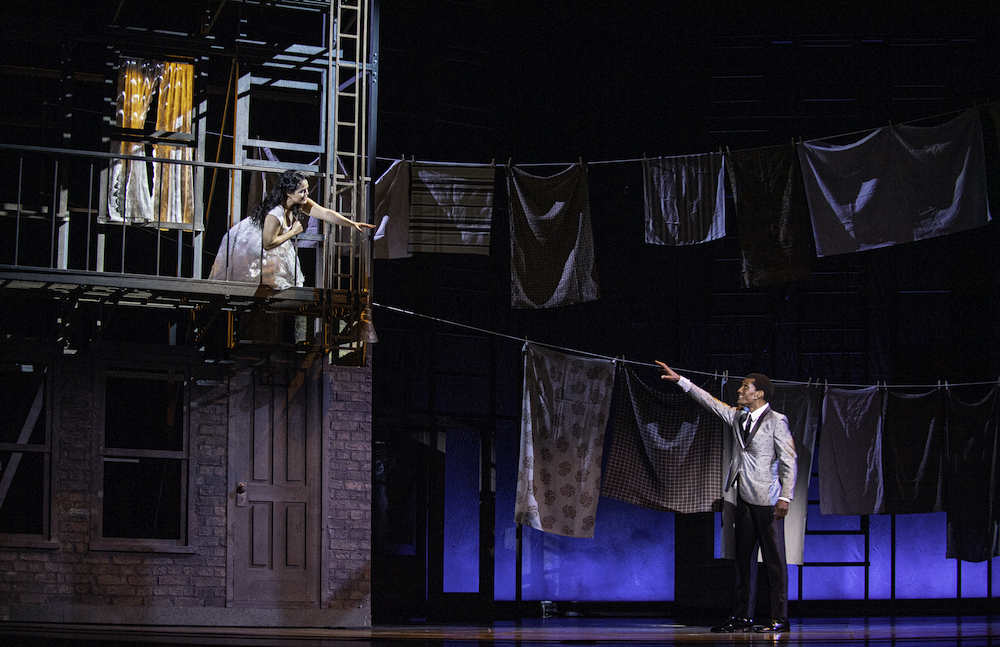

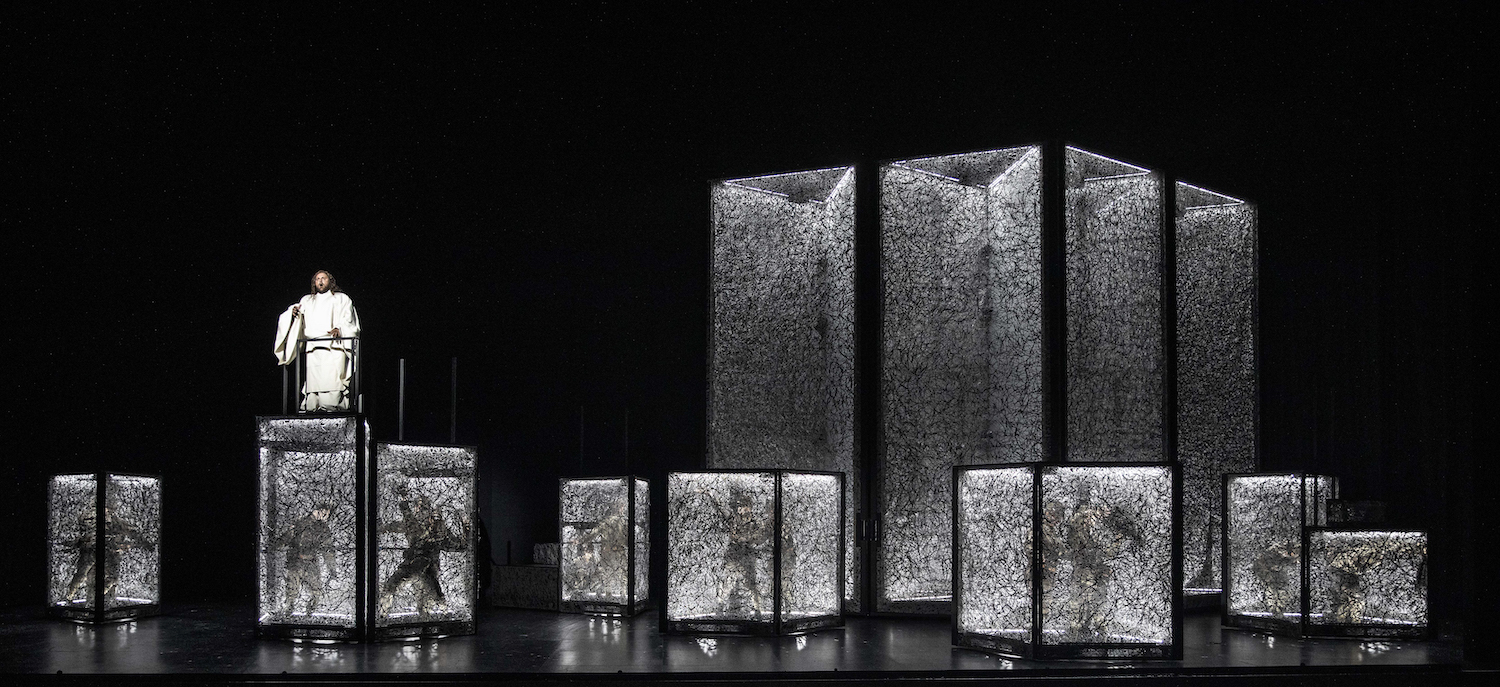

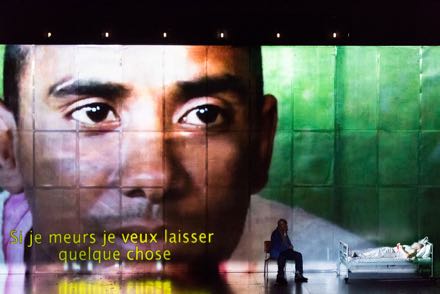

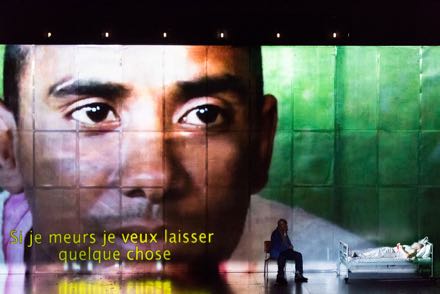

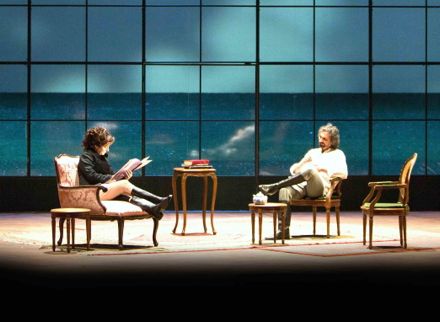

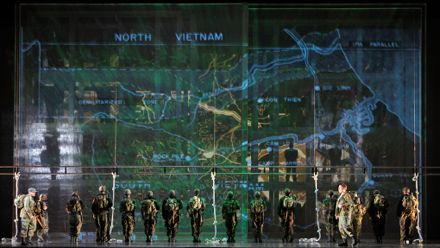

Steve Jobs presenting the iPhone. Set design by Victoria Tzykun, projections by 59 Productions

Steve Jobs presenting the iPhone. Set design by Victoria Tzykun, projections by 59 Productions

The book, by well-known opera librettist Mark Campbell, is a prologue, eighteen scenes and an epilogue that traverse, out-of-chronological-order, crucial moments in a progression of the Jobs obsession — his demand for simplicity and elegance, his denial of his basic humanity, his tenuous relationship with a Zen master, his dismissal of human responsibilities, his defiance of business models, his dependence on his wife. The disease, be it cancer or obsession, is established from the beginning, and in the end there is the final flash, the blast of intense white light that is the real, ground zero destruction.

Or was it connection.

Within the eighteen scenes Mr. Campbell has created the lyrical moments, in arias, duets and trios, that conspire to make a dramatic progression, much like a Handel opera. Many of composer Mason Bates’ set pieces are absolutely gorgeous, in vocal lines that flow with lyrical elegance, and ease. The arias will likely become audition pieces for singers, given that they have impressive vocal requirement, and demand solid dramatic skill to pull off.

The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs holds a huge amount of composed music, of even superhuman magnitude, to the degree that you know this music had to have been created with mechanical aids — the technologies exploited by the Jobs Silicon Valley world. The musical style is basically Straussian, massive details in myriad tonalities, never straying too far from some sense of tonal center, and always seeming to go directly somewhere. And loud, very loud.

Among the conceits of the libretto is the likening the joys of obsessive work to musical sounds, to Bach, to oboes and flutes, etc. To our relief Mr. Bates’ score does not take this literally. Perhaps the Bach moments are somewhat more structural, perhaps the instrumental references are given in somewhat sweeter sound. There is always a lot going on in the Bates sonic world, most of which defies easy definition.

It is big band, solid wall sound without many specific, emotional colors, created by limited winds (though two alto saxes), but very ample brass and full strings. There is amplified guitar for ears accustomed to such sound and lots of small percussive punctuation particularly in the libretto’s Zen references. And electronics: two MacBook Pros (played just now by the composer).

Composer Mason Bates playing his two MacBook Pros at a San Francisco Opera Orchestra rehearsal

Composer Mason Bates playing his two MacBook Pros at a San Francisco Opera Orchestra rehearsal

The production staff, originally assembled by the Santa Fe Opera, is headed by stage director Kevin Newbury, well known in progressive opera circles, who worked with well known New York based Ukrainian multimedia artist Victoria Tzykun as the set designer. The lighting designer Japhy Weideman boasts Broadway credits, and the team behind the extensive projections, 59 Productions, boasts Las Vegas and Bilbao credits.

In this ninth edition the production showed itself as very slick, practiced, Broadway style theater. Though one assumed the six, sizable moving panel, actually boxes, that functioned as the set were magically, flawlessly moved, magnetically at the very least, by Silicon Valley technology. The information sheet given the press however indicated that they were physically moved by 12 stagehands, the myriad projections on their surfaces effected from within.

Thus we have been assured, theatrically at least, that machines have not replaced humans, disproving the opera’s premise, or proving the opera’s premise that even Steve Jobs was human.

The singers, including the 24 choristers, were skillfully amplified, credited to sound designer Rick Jacobsohn, making the words delivered by the skilled singers easily, uniformly accessible.

From the original Santa Fe Opera production comes conductor Michael Christie, mezzo soprano Sasha Cooke as Steve Jobs’ wife Laurene, and Chinese bass Wei Wu as the Zen master. Both singers and maestro Christie are on the Grammy Award winning recording that came out of the Santa Fe premiere.

It is unclear from the program bios which of the various editions of the production were sung by John Moore as Steve Jobs and Bille Bruley as Jobs’ best friend Steve Wozniak, but these fine, practiced performances were not role debuts.

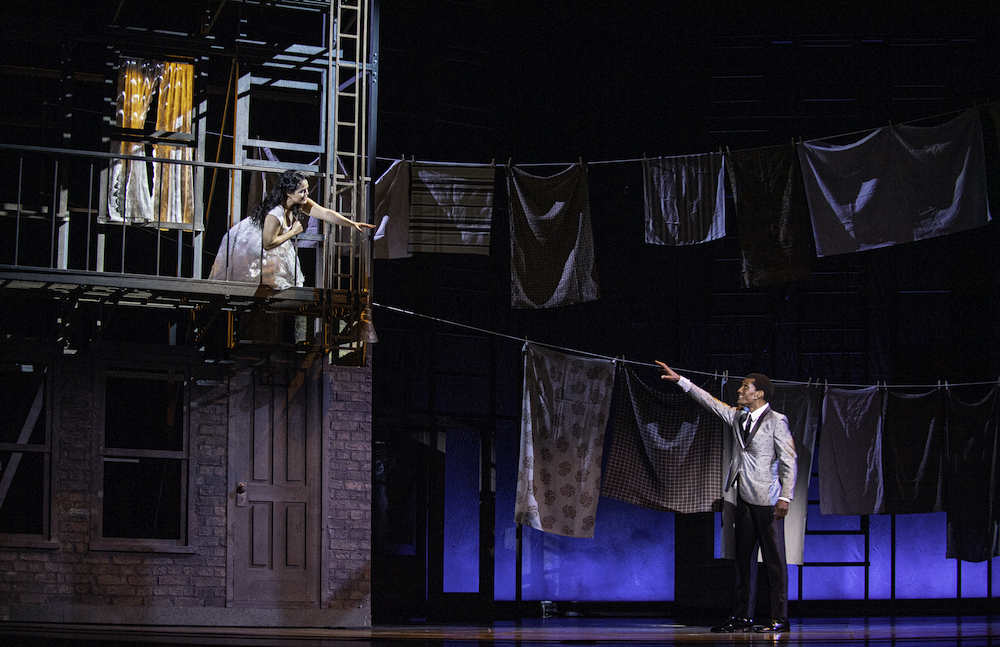

John Moore as Steve Jobs, Olivia Smith as Chrisann Brennan

John Moore as Steve Jobs, Olivia Smith as Chrisann Brennan

Adler Fellow Olivia Smith gave a moving portrayal of Chrisann Brennan, Jobs’ rejected girl friend and mother of his daughter Lisa (a name, librettist Campbell has Jobs say, better suited to an operating system). The pivotal moment when the Reed College teacher imparts to Jobs the significance of a completing a circle was effectively delivered by Adler Fellow Gabrielle Beteag. The myriad small roles were undertaken by members of the San Francisco Opera Chorus.

The epilogue returns to the beginning, Jobs father Paul presenting his son with a simple work table, but now looked upon by Steve Jobs wife Laurene. It was a compelling evening at San Francisco Opera. Steve Jobs was one of us. Mason Bates is one of us.

War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco. October 3, 2023Il trovatore at San Francisco Opera

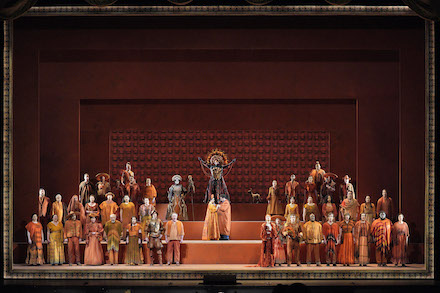

Enrico Caruso said that Trovatore is easy — you just need the four greatest singers in the world. Let us not argue about who these singers may be. Do let us congratulate San Francisco Opera for assembling a full cast of equally excellent singers who well fulfilled the vocal challenges of this unruly opera.

A feat rarely achieved, anywhere, and newsworthy indeed when it does.

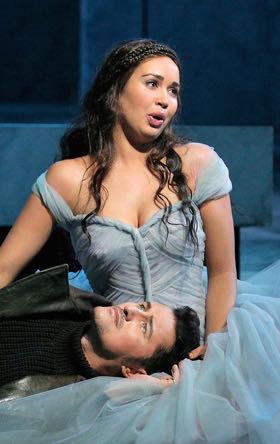

That’s Russian mezzo soprano Ekaterina Semenchuk as Azucena, L.A. born and finished soprano Angel Blue as Leonora (role debut!), Mexican tenor Arturo Chacón-Cruz as Manrico, and Romanian baritone George Petean as the Count di Luna. For good measure throw in Canadian bass Robert Pomakov as Ferrando.

Verdi famously toyed with the idea of naming the opera La Zingara (The Gypsy), only later deciding to enlarge the role of Leonora, greatly complicating the plot. Verdi originally had been intrigued by the then recent Spanish play El Trovador, with its gypsy heroine. Such a marginal heroine as centerpiece would complement his operas about a freak (Rigoletto) and a whore (La traviata), allowing the composer to exploit absolutely new and shocking subjects. Voilà the three famed, middle period masterpieces.

But Verdi was not able to forsake his fascination (and the Italian obsession) for fallen women, adding the exquisite Act IV Leonora aria and scene, later echoed in the fourth acts of Don Carlo and Otello. Thus Il trovatore became an opera about two women — a marginalized woman of color who has placed a curse on an aristocrat, and an aristocratic woman whose purity is questioned. Not to mention the two guys caught in the middle of a war against each other.

Undaunted by overburdening his opera with elaborations of current (then and now) issues Verdi charged ahead, creating music that is absolutely overpowering.

And overpowering it was just now in San Francisco. British designer Charles Edwards created a show curtain based on the 1823 Goya painting “A Pilgrimage to San Isidro,” though it is but a detail. Its visible screams seemed right-on for the domestic tragedies that were to play out on the stage apron, positioning that kept the singers directly under the baton of the conductor.

Show curtain, a detail of Goya's painting “A Pilgrimage to San Isidro”

Show curtain, a detail of Goya's painting “A Pilgrimage to San Isidro”

San Francisco Opera music director Eun Sun Kim makes her pit very present. It was raised even higher (and louder) for this David McVicar production to accommodate the additional height of a revolving stage. Verdi is loud, Il trovatore is particularly loud, Ma. Eun Sun Kim finds a lyric pulse that never falters. Add this to the obvious excitement of this conductor working with these responsive singers in this, the most singerly opera in the repertory — at best there were enrapturing periods of lyric splendor, at worst it was a musical caricature of Verdi’s opera.

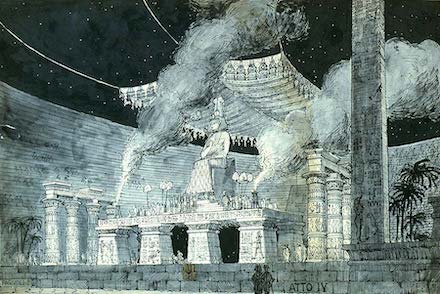

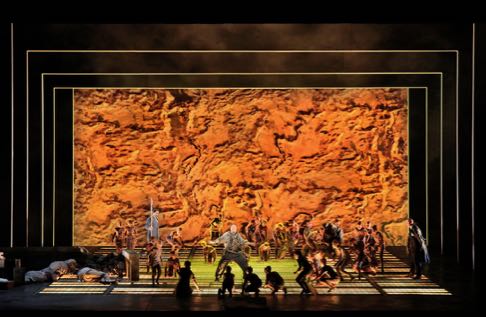

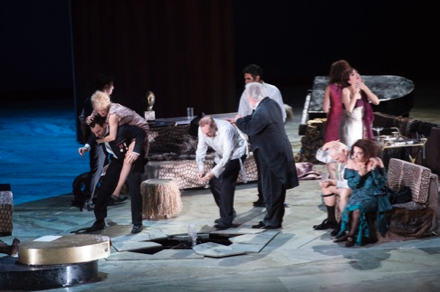

This McVicar production was first staged in Chicago in 2006, remounted both in San Francisco and at the Met in 2009, revived by the Met in 2017/18, then in Chicago in 2019, It is considered among this prolific British director’s finest productions. The conceit of the production is Goya’s print series “The Disasters of War” that places the action not in El Trovador’s early 15th century, but during Spain’s early 19th century war against Napoleon.

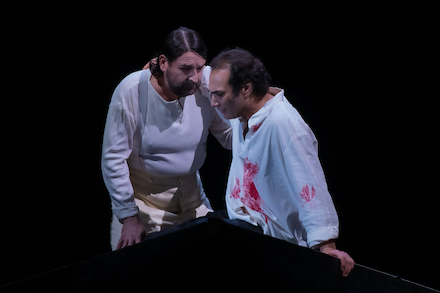

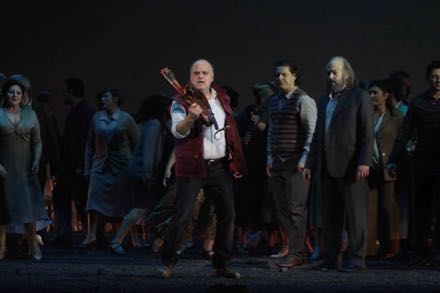

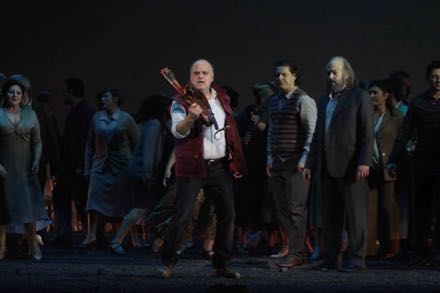

Ekaterina Semenchuk as Azucena (barely visible on the left)

Ekaterina Semenchuk as Azucena (barely visible on the left)

The larger stage pictures with chorus were meticulously recreated by revival stage director Roy Rallo, the splendid lighting was in the hands of the production’s original lighting designer Jennifer Tipton. Charles Edwards towering sets revolved with determined resolve to portray the ineluctable brutality of war.

Though any thought of war, any war anywhere anytime, was far from our minds as the dramatic tensions of vengeance and purity flared so mightily on conductor Eun Sun Kim’s stage apron. The production was irrelevant.

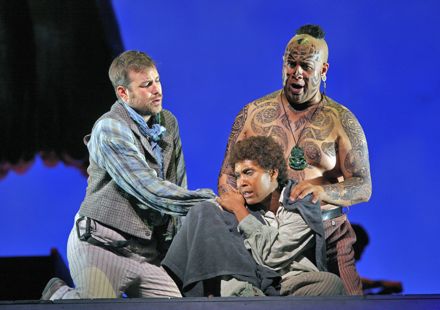

Mezzo soprano Ekaterina Semenchuk as Azucena had been underwhelming as Santuzza and Amneris in recent San Francisco Opera productions of Cavalleria Rusticate and Aida. Now, under Ma. Kim’s baton, she was electrifying as Azucena. Her voice is purely and warmly toned, not Italianate, her delivery was impassioned and fiery. Defying all musical decorum, it was an unleashed performance. Interestingly her program booklet bio was surprisingly brief, not mentioning that she replaced Anna Netrebko as Verdi’s Lady Macbeth in a 2022 Munich production, evidencing her political viability on Western stages.

Soprano Angel Blue as Leonora evidenced remarkable vocal technique in her debut in one of opera’s most demanding roles. She has a clear, limpid tone that is uniquely suited to the purity of a Verdi heroine, and a soft presence that allows her to be both young and innocent. Her voice exhibits the requisite, considerable heft for this spinto role, determining a rich future in the dramatic soprano repertory — already this past May she had success as Verdi’s Aida at Covent Garden.

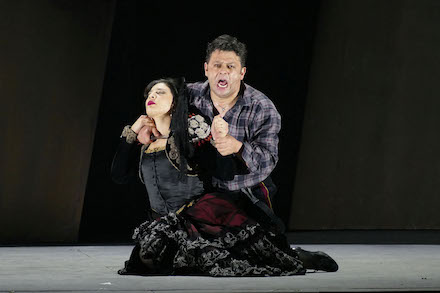

Tenor Arturo Chacón-Cruz as Manrico has the lyric finesse to embody a true 15th century troubadour, a quality he grandly exploited in his two off-stage serenades of Leonora. On stage he belted a plentitude of ringing high notes while commanding a youthful elasticity in negotiating Verdi’s flowing lines. He faltered in his big third act aria moment, usually a show-stopper, giving us fear that the strong voice he had used so effectively had worn out. Reports from earlier performances indicate that this was probably not the case. Like many of us, it is likely that he suffered under the wildfire smoke blanketing San Francisco.

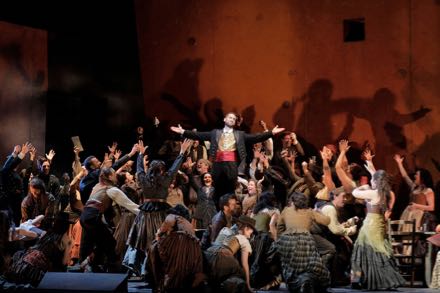

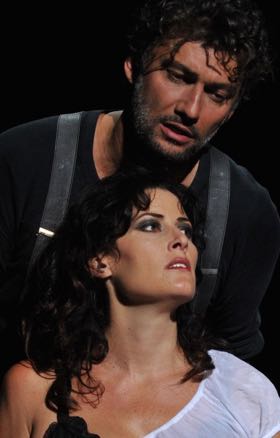

Arturo Chacón-Cruz as Manrico, George Petean as the Count di Luna

Arturo Chacón-Cruz as Manrico, George Petean as the Count di Luna

Baritone George Petean as the Count di Luna is foremost a singer, a very fine one. He made a one-dimensional villain, never convincing us he was a serious suitor to Leonora. Verdi gave him ample opportunity to do so by providing him a lovely aria proclaiming the depth of his attraction to her. With conductor Kim he rendered the aria as a virtuoso moment, and it was indeed impressive. Mr. Petean’s Count di Luna was all bluster.

Bass Robert Pomakov as the Count di Luna’s captain of the guard was rough voiced, well able to embody the military postures envisioned by the McVicar production. As well he suited the vocal flash urged by the conductor. Missing was the bel canto vocalism of his aria that opens the opera, giving us its back story as well as preparing us for the vocal fireworks that define this middle period masterpiece.

War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, CA, September 18, 2023.

All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera.

El Ultimo Sueño de Frida y Diego at San Francisco Opera

History according to opera is a wondrous thing. Just now in San Francisco Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera have gone off into the sunset (eternity) together, happily reconciled. All this thanks to the most colorful and festive festival of them all, called Dia de los Muertos!

Though the same day as All Souls’ Day (November 2) when Old World Christians remember their dear departed families, New World Mexican Christians allow their dead to come back into the world for this one day, with the help of the Aztec Goddess of Death, Catrina who serves Mictēcacihuātl, Queen of the Aztec underworld.

Here’s the action of the opera: Diego comes into a Day of the Dead altar (huge), where he begs Frida, now a resident of the underworld, to come to him (the couple was famed for the impossibility of being together and the impossibility of being apart). Down there, goddess Catrina implores Frida to return to Diego. After great hesitation, and consultation with a Greta Garbo dressed countertenor, Frida agrees to the rules — 24 hours max, no caresses. Frida and Diego take a walk in Alameda Park where they meet the Greta Garbo travesty. They all go to Casa Azul [Frida’s actual home, now a museum] where Frida eventually embraces Diego after all. She is racked by pain. Diego wants to follow Frida back into the underworld. He does.

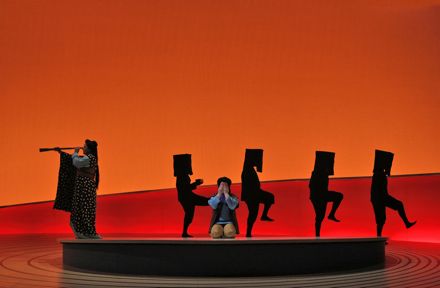

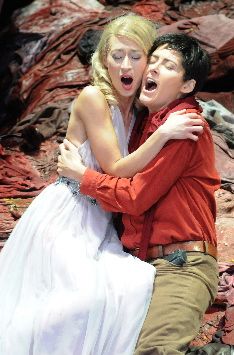

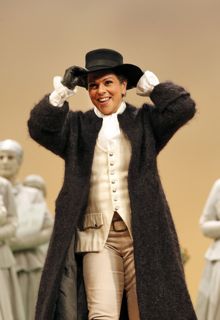

Yaritza Véliz as Catrina, Daniela Mack as Frida

The opera is a musical meditation on textural elaborations of each of these settings and situations, created by Cuban American playwright Nilo Cruz. The libretto is divided into 21 relatively brief scenes, much like Wozzeck’s 15 scenes and Death in Venice’s 17 scenes, that manage to describe the bodies of the artists, to explore the creative impasses suffered by both artists, to mention their flamboyant sexual encounters (including a lesbian reference), all this while imparting the fatal attraction of Frida and Diego and evoking the colors, excitement and majesty of the Day of the Dead.

American composer Gabriela Lena Frank, whose mother is of Chinese Peruvian descent and whose father was in the Peace Corps in Peru, created the music, investing the text with a flow of comprehensible intervals that sometimes become chiseled. It was in keeping with contemporary standards of setting texts, eschewing the stepwise progression of normal speech. There was as well a pleasing use of melisma to embellish text, a reference South American music and to the Latina persona Mme. Frank has embraced.

Complying to the budgetary restrictions of American opera companies, Gabriela Lena Frank scored her opera for double winds, not too many brass, timpani, two percussion, harp, piano/celeste and strings. The celeste was used from time to time to create quite beautiful flights of exotic tone outside the normal orchestration, much like Peruvian flutes. As well she created wind instruments flights, exact replicas of Benjamin Britten’s riffs of sexual infatuation in Death in Venice. There were, disappointingly, very few moments of blaring brass, barely hinting at, never imitating Mariachis.

Mme. Frank is a conservative composer, giving extended life to twentieth century European musical style.

The production was however totally Mexican. Sra. Lorena Masa was the stage director, gold framing the Day of the Dead altar, and gold framing smaller portraits of the opera’s players from time to time, finishing the opera with Diego and Frida in the framed pose of the wedding portrait she painted while they lived in San Francisco. Set Design was by Jorge Ballina who conjured a fine Day of the Dead altar that cannily rose to hover over the underworld, then created a Diego studio and Frida Casa Azul worthy of famed Mexico City architect Luis Barragan, all on the platforms on which the final tableau stood — the forty choristers and, finally, the Queen of the Underworld (though she did not sing) — in golden, Aztecan glory.

The final scene

Costumes were created by Sra. Eloise Kazan in touristically referential Mexican styles. There were as well exotic costumes, like the goddess Catrina and the underworld queen, not to mention the Frida costumes, based on her famous get ups.

The real costume show was however to be seen in the lobby — the costume designer herself wore a grand headdress (gratefully removed during the performance as she sat in front of me), the light green silk brocade jacket and matching tie of Sr. Victor Zapatero, the lighting designer, was spectacular. There were fine, embroidered shirts worn by the many Latinos in the audience, and restrained and outrageous attempts at Frida colors and style on both men and women. It was a very festive, very dressy audience.

Frida was sung by Argentina born, mezzo soprano Daniela Mack who found Frida’s brashness, her confidence and her vulnerability in a strongly sung performance. The role is lengthy and obviously difficult, delivered with pleasing elan by Mlle. Mack. The opera gives vocally spectacular fireworks to the goddess Catrina, sung by Chilean soprano Yaritza Véliz who delivered as required. Leonardo, the Greta Garbo travesty role was sung by American countertenor Jake Ingbar with a warm, masculine soprano tone, and acted the role with feminine aplomb. Mexican baritone Alfredo Daza had the probably impossible task of playing Diego Rivera — a trouble-maker with an enormous personality, and a prolific lover as well. Mr. Daza is a fine singer indeed, who gave it his best shot. Mexican conductor Roberto Kalb urged the San Francisco Opera Orchestra to a polished, full bodied reading of the score, making its more exotic moments shine brightly.

For the first time in its 100 year history the San Francisco Opera Chorus was asked to sing in Spanish! The chorus presence in the tableaus of El Ultimo Sueño de Frida y Diego was huge, and it is difficult music. It was a virtuoso performance by this superb chorus.

Composer Gabriela Lena Frank is currently the resident composer of the Philadelphia Orchestra. She lives in Boonville, CA.

War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, June 13, 2023. All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera

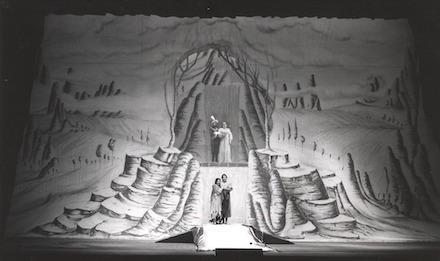

Die Frau ohne Schatten at San Francisco Opera

The fifth opera of the lengthy Richard Strauss canon, The Woman Without a Shadow (1915) is surely the richest work of them all, traversing real and imaginary worlds while proving its actors worthy to receive the fruits of love. Just now in San Francisco it was the David Hockney production, first seen 30 years ago at Covent Garden and L.A. Opera.

Die Frau Ohne Schatten is no stranger to San Francisco, the opera marking its American premiere at the War Memorial Opera House in 1959 in a production by the then 27 year-old Jean-Pierre Ponnelle. This gifted designer/director quickly became the avant-garde star of the then progressive San Francisco Opera.

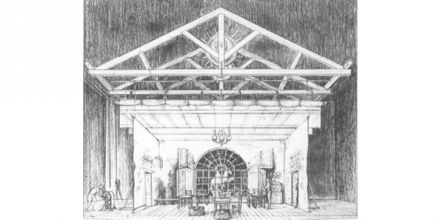

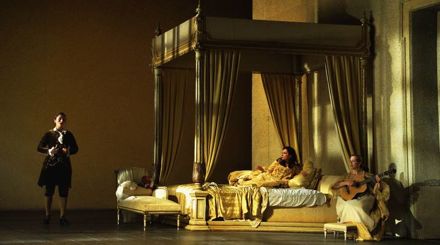

The final quartet of Die Frau ohne Schatten. Jean-Pierre Ponnelle's settings often resembled colorless pencil sketches.

The opera returned in 1976 in a production by Nikolaus Leinhoff from the Stockholm Opera designed by Jorg Zimmermann, its 1980 San Francisco revival notable for Brigit Nilsson’s Dyer’s Wife. James King sang the Emperor with Leonie Rysanek as the Empress.

The Dyer's hut in the Lehnhoff production.

The challenges of mounting Die Frau Ohne Schatten are daunting, not only the casting of five heroically voiced singers, making space for a Strauss orchestra of nearly a hundred players, finding places for big off-stage choruses and backstage banda instruments, but also for the instantaneous, back and forth transformations of the stage from the poor dyer’s hut of a Scandinavian fairytale to the magical landscapes of a medieval Indian sultan.

The David Hockney 1992 production finds a balance between these worlds, as well as merges the Mozartian and Wagnerian thematics that co-exist in the libretto, all this within the hyper post-Romanticism of the Strauss score. No small feat.

Act I. The nurse offers carnal love to the dyer's wife. Left to right Linda Watson as the Nurse, Nina Stemme as the dyer's wife, Camilla Nyland as the Empress.

Hockney’s operatic world is filled with brilliant color (his The Rake’s Progress is an explicable exception, i.e. it is Stravinsky’s dry neo-classicism). Like Messiaen and Scriabin Hockney was born with synesthesia — seeing color is his response to music. To this add the modeled linear flow of musical line, and the Hockney obsessive manipulation of perspective. Die Frau ohne Schatten was destined to become a part of the Hockney operatic oeuvre, joining The Magic Flute, Tristan and Isolde, and Turandot, all works of enormous musical color and fantastical content.

San Francisco Opera expanded its pit in 1976 to accommodate enlarged 19th and 20th century orchestras, and specifically at that moment to entice legendary conductor Karl Böhm to conduct Die Frau ohne Schatten. In more recent times, with the institution of a music directorship (lacking during the Kurt Herbert Adler years), the San Francisco Opera Orchestra has developed into one of the world’s fine opera orchestras. Plus current opera house practices have increased the number of orchestra rehearsals, priming the pit just now for this superlative collaboration with the famed visual artist.

Former music director Donald Runnicles returned to San Francisco Opera for this production, as he has for the two recent Wagner Ring cycles. Mo. Runnicles’ musical identity is rooted in the huge Romantic and post-Romantic repertory, thus he mined all possible richness and volume from the Strauss score, reveling in its myriad musical colors. It is a huge orchestra playing big music about what, one is not sure.

The final quartet. Left to right Camilla Nyland as the Empress, Nina Stemme as the dyer's wife, Johan Reuter as Barak, David Butt Philip as the Emperor.

Surely it is about more than the dyer and his wife discovering that their humble love will transform into children who will then discover in turn that love will, in principle, prevail eternally. All this while Europe is sitting on a powder keg waiting for the spark that did indeed soon strike. Die Frau ohne Schatten seems to hold all this explosive geopolitical might within its massive dramatic tensions. They would not explode if only the Nurse in the opera had her way — that the shadow of the Dyer’s wife would be stolen so that the emperor would not be turned to stone.

So maybe Die Frau ohne Schatten is simply about making art, not war.

San Francisco Opera has given to art its all, assembling a cast whose voices could be well heard through the orchestral forces.

Famed Swedish soprano Nina Stemme was the dyer’s wife whose shadow was not stolen after all (see lead photo). Mme. Stemme, now sixty years old, is in fine voice, well able to sustain her beautiful, powerful high tones, if without all the brilliant luster of her 2011 San Francisco Brünnhildes. Importantly Mme. Stemme did actually project a sense of character adding a real humanity to the role, while never sacrificing its heroic vocalism. A greater warmth of tone in her mid voice would have enriched her reconciliation with Barak, her husband.

The dyer Barak was sung by Danish bass-baritone Johan Reuter. He too projected the humanity of his role, providing the warmth of character that librettist von Hofmannstahl and Strauss sought, winning our sympathy by sparing his donkey a weight of burden, and expressing his fear that he would not be able to feed his eventual children.

David Butt Philip as Emperor in the Falcon house.

The Emperor was sung by British tenor David Butt Philip whose voice is very beautiful indeed. His second act visit to the falcon house (his falcon had wounded a gazelle who then turned into a woman — the Empress) was the most beautifully sung, indeed truly magical scene of the performance. The role lies high, and the vocal lines are extended making it a virtuoso display, achieved with consummate ease by Mr. Philip.

The Empress was sung by Finnish soprano Camilla Nyland whose voice is of a beautiful, silvery tone that brilliantly negotiated the lengthy, high tessatura of the role. It is a voice that, with Mr. Philip’s Emperor, could take us into the magical, loftier world of pure beauty, but only if she could find a shadow. The Empress effects the dénouement of the opera in the huge, fountain-of-life scene where she refuses to sacrifice the earthly love of the Dyer and his wife (and their eventual children) to gain her shadow, and the Emperor is thereby turned to stone. Mme. Nyland effected the scene without ascending vocally or dramatically to its potentially spiritual heights.

The Nurse was sung by American soprano Linda Watson who sings both Herodias at La Scala and Isolde in Dusseldorf. She combined both roles for this production, deftly driving the role’s machinations that seemed to be more motivated by pure evil rather than by love and protection for her mistress, the Empress. As well she fearlessly drove an oarless boat to the temple in India or somewhere where she was then soundly dismissed by her mistress.

All this magnificence found its way onto the War Memorial Opera House stage with the deft guidance of stage director Roy Rallo, with the very able assistance of lighting designer Justin A. Partier, both men bringing vibrant new life to the Hockney production.

War Memorial Opera House, June 10, 2023. All photos courtesy of San Francisco Opera, photos of the Hockney production are copyright Cory Weaver.

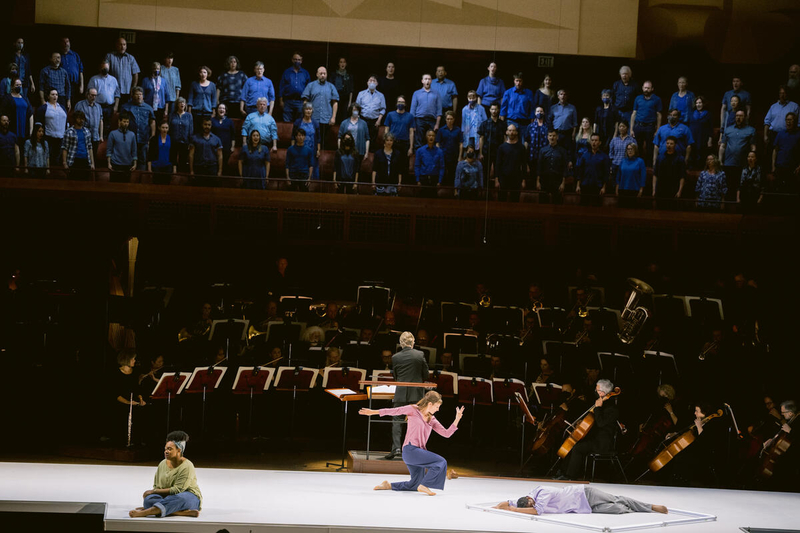

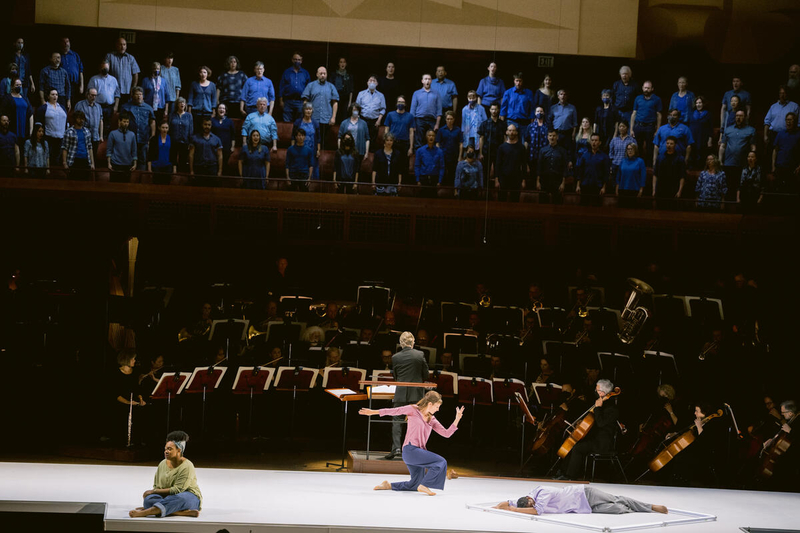

Adriana Mater at San Francisco Symphony

June in San Francisco may become one of the world’s great opera festivals. In recent years the San Francisco Symphony has added a staged opera in its concert hall to complement the three operas happening across the street in the War Memorial Opera House.

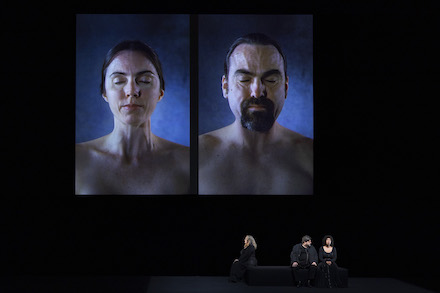

Just now San Francisco Symphony music director Esa-Pekka Solomon with stage director Peter Sellars have placed Kaija Saariaho’s 2006 opera Adriana Mater on four small platforms inserted into the orchestra itself. A very few lighting instruments hang from four huge trusses suspended from the Louise M Davies Symphony Hall ceiling, lights that color the platform tops in various hues from time to time. A few more lighting instruments are strategically placed to focus strong light onto the faces from time to time, plus there is a bevy of inconspicuous loud speakers to project the text clearly and forcefully.

Add the San Francisco Symphony of triple winds, quadruple brass, piano/harp/celeste, two tympani sets, strings and a percussion battery of twenty-eight implements divided among five or so players. Members of the San Francisco Symphony Chorus sat high above the stage adding amplified sound textures.

Nothing more, nothing less.

Adriana Mater is the second of Saariaho’s three full scale, actually huge scale operas, the first is L’Amour de loin (2000), the third is Innocence. (2018). While L’Amour de loin may be the lush contemplation of a woman by a medieval troubadour it dives deeply, indeed quite anxiously into obsession and devotion in a world of reality and illusion, and the human need to belong somewhere. These are themes which dominate Innocence as well — a wedding reception gone awry against myriad recollections of a school massacre, and a mother daughter crisis.

Innocence, considered the Saariaho masterpiece, comes to San Francisco Opera in 2024 in the Simon Stone production from the Aix Festival. https://operatoday.com/2021/07/innocence-at-the-aix-festival/

These are not dramatic works. Rather they are three contemplations of the terrifying realities of twenty-first century existence. Balance these massive works against the huge catalogue of orchestral works, concertos, cantatas, and chamber works for solo or few instruments, and voice that Kaija Saariaho (1952-2023) has bequeathed us to understand that there is much more to her musical spirit than the sensationalism of these operas.

Foremost, Adriana Mater (Innocence as well ) is a huge, operatically voiced cry/scream about violence — war, rape, and guns — laying bare the souls of those in its midst. That the protagonists are female is fitting, though Mme. Saariaho has preferred to be known simply as a composer rather than as a female composer. The librettist of Adriana Mater, Amin Maalouf, is male.

Though he was born in Lebanon he immigrated to France, like Mme. Saariaho (born in Finland), early in life. Though Arabic is his first language he has always written in French as a war correspondent, novelist and librettist. Like Mr. Maalouf, it may be said that Mme. Saariaho composed in French given that her compositional maturity occurred in France. Her participation at the famed Parisian Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music (IRCAM) rendered her a spectralist (among the successors to Olivier Messiaen), and added electronic manipulation as an integral component of her composition.

Mr. Maalouf’s libretto tells of a drunk man with a gun who rapes a woman who, against the advice of her sister, gives birth to a son who she hopes will not be a killer. The son, now an adult, learns that his father was a rapist, and is still alive. The son sets out to kill his father who, he discovers, is now blind.

Though the story is told from the perspective of the mother (mezzo-soprano) the story shifts in and out of the perspectives of her sister Refka (soprano), Adriana’s son Jonas (tenor) and the father Tsargo (bass), the four voices in the opera. The Peter Sellars staging places the singers among the orchestra on platforms, with no visual references save a sometimes colored floor. Besides the evident closeness of vocal and orchestral collaboration, this stark focus on each player muted the violence of war and alcoholism and took us deeply into the minds and hearts of each of the players.

Within Mme. Saariaho’s carpet of the sounds of infinite possibilities, we discerned the quite magnificent angst of the players, and their human, philosophic and metaphysical stances. There were constant bursts of human spirit that erupted through this maze of orchestral confusion, and these bursts were not comforting, nor did they portend any answers. Notable was use of a descending minor second (smallest interval of the chromatic scale) to land on the [a]tonality of the soundscape that identified a particular moment. Startling was the absolute absence of any hint of diatonic harmony, even in the resolutions of a scene.

Adriana was sung by mezzo soprano Fleur Barron, an artist of Asian/European descent, formed in New York. Of rich voice, she is a formidable technician of deep musicality and has a powerful stage presence, transforming herself from the sexually ripe young woman into the mature woman who must explain herself to her grown son. The young soldier/rapist who then becomes a blind old man was sung by bass-baritone Christopher Purves, a veteran opera singer of huge accomplishment. Spellbinding as the blind old man, he lay supine with his back to us, his voice electronically modified into sepulchral tones.

Ariana’s sister was sung by Parisian formed soprano Axelle Fanyo. Of rich voice and impeccable technique she negotiated the treacherous vocal lines created by Mme. Saariaho with an ease that made such atonality of line seem natural. Ariana’s son was sung by American tenor Nicholas Phan of Asian/Greek descent (mentioned only because stage director Sellars has particular affection for mixed race artists). Mr. Phan brought striking artistic finesse to this very complex role — raging at his mother, berating her sister, threatening his father. He lay his Uzi down finally, a gesture of unanswered peace.

Note that the singers relied on iPads to prompt their lines, a conceit that seemed just right in the context of the complexities of the literary and musical concepts. Their voices were always amplified, thus we had no idea of the sizes. The sophistication of amplification was such that the voices were felt to emanate from their stage positions. The excellent sound technicians were not recognized in the program.

The lighting, of ultimate sophistication, was by James M. Ingalls, a long time Sellars collaborator.

Louise M. Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco, June 8, 2023. All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Symphony.

Madama Butterfly at San Francisco Opera

Japanese stage director Amon Miyamoto’s Madama Butterfly was first seen in Tokyo, then traveled to Dresden before arriving just now in San Francisco. Unlike Puccini who made the tiny Japanese geisha his tragic heroine director Miyamoto made the American lieutenant Pinkerton the central figure in his take on San Franciscan David Belasco’s play of the same name (1900).

Further directorial revisions rendered this monument of Italian operatic verismo into the Grand Guignol theater (horror theater) of Puccini’s short story tryptic Il trittico [Il tabarro/Suor Angelica/Gianni Schicchi]. The dominant image of this Madama Butterfly was the deathbed of an aged B.F. Pinkerton that opened the show in absolute silence, and closed the show in Puccini’s violent thunder clap of emotional release.

Conductor Eun Sun Kim squelched its final cymbal crash with astonishing alacrity, capping once-and-for-all the hyper indulgent musicality of the evening.

The deathbed image of the Puccini’ comedic Gianni Schicchi hung heavily over this evening, furthering the sense that this full, three act opera was really only the short story it once was, with an interesting point it wished to make. To wit: a bi-racial child, here a thirty year-old man, must struggle mightily to reconcile his heritage.