Opera Houses

Jean-Paul Scarpitta (March 2014)

The Opéra de Marseille (June 3, 2013)

Opera House Fires in the South of France (2007)

Note: This page holds descriptions/evaluations of many of the CapSurOpera theaters, and sometimes brief historical accounts.

Jean-Paul Scarpitta, general director

Opéra Orchestra National Montpellier, 2011-2013

I met with the embattled artistic director of the Opéra et Orchestre National de Montepellier not to talk about his battles. I simply wanted to know the man who had cast and staged a truly extraordinary Mozart/DaPonte trilogy.

Jean-Paul Scarpitta however wanted to talk about his battles, a situation he has not yet spoken about publicly. As the luncheon meeting progressed the battles, the man and his Mozart trilogy merged into a single philosophy created of quite complex components.

Jean-Paul Scarpitta

(photo Marc Ginot / Opéra Orchestra National Montpellier)

It all starts with composer René Koering who brought Jean-Paul Scarpitta to Montpellier in 2001 for a small mise en scène of Saint-Saêns’ Carnival of the Animals. Koering who had a long standing programming connection with Radio France founded the Festival de Radio France et de Montpellier Languedoc-Roussillon in 1985. Always a forum for rare music and performances, in the first decade of the next century this superb summer festival was especially noted for reviving forgotten operas from the early twentieth century.

In 1990 Koering became the director of the Opéra Orchestre National de Montpellier (OONM), bringing the ideals of the festival into the daily musical life of Montpellier — a broad program of symphonic and chamber music, original productions of rare and standard opera at ticket prices that encourage filled halls (top prices even in 2014 are but 32 euros for concerts and 65 euros for operas plus there are substantial discounts for subscribers and those under 27 years of age).

Montpellier’s 250,000 residents are part of an urban area that counts 550,000 inhabitants, making it the fourteenth largest metropolitan area in France. Its Opéra however is one of only five regional companies (with Bordeaux, Nancy, Lyon, and Strasbourg) that are designated as national, denoting a stature more or less akin to the Opéra National de Paris.

Jean-Paul Scarpitta returned to the festival in 2004 to stage Kodály’s singspiel Háry Jànos. But with a twist. Scarpitta brought his friend Gérard Depardieu with him to narrate Kodaly’s tale about a country bumpkin who arrives in Vienna. Scarpitta’s first steps as a metteur en scène had been back in 1997 for Stravinsky’s A Soldier’s Tale at Paris’ Théâtre des Champs-Élysées with Depardieu as the soldier. I asked how he knew Depardieu. Scarpitta said that he had gone backstage after a performance to introduce himself. Responding to my un-asked question Scarpitta said that you accept your friends as they are.

Conductor Ricardo Muti has been an important force in Scarpitta’s artistic life for the past 20 years. I asked how he came to know the famous maestro. Scarpitta said he introduced himself going backstage after a performance, greatly moved by the music.

The young Scarpitta

(photo source Wikipedia)

Scarpitta confessed that he needs to admire. An adolescent, his greatest admiration was of ballerina Ghislaine Thesmar who later became a star at the Paris Opera Ballet in the 1970‘s, and a frequent guest star at the New York City Ballet as well. Scarpitta told me how he, a student of art history, followed her to New York with his camera, documenting her work with George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins. Another photographic adventure as well helped propel the young Scarpitta to recognition in Parisian artistic circles — he compiled an exhibition of 50 years of fashion photography in Vogue magazine, an exhibition that toured the world.

I neglected to ask what repertoire Muti conducted the night Scarpitta met the maestro. Maybe it was Mozart, a composer Muti became close to in his forty year association with the Vienna Philharmonic. The Italian conductor is famous for his strongly personal Mozart, fusing intelligence, elegance and wit, attributes that as well extend to the stagings of the Mozart/DaPonte trilogy by Jean-Paul Scarpitta.

For Scarpitta art is line and form and tone, in music, dance and photography. But above all else Scarpitta insists that it is heart. Scarpitta announced to me that we are all Don Giovanni.

Those many years ago Muti told Scarpitta that he needed a theater where he would make his own art. Scarpitta’s was appointed general director of the OONM in 2011, fulfilling finally Muti’s assertion. That same year Muti invited Scarpitta to stage Nabucco in Rome. The production became famous not because of Scarpitta’s staging but because at the premiere Muti laid down his baton after the "Va pensiero" chorus to speak to the audience about the Berlusconi budget cuts to the arts, quoting a line from the chorus, “Oh mia patria, sì bella e perduta (lost).”

Muti then invited the public to sing along in a repeat of the famous chorus. Learn the words before you attend Nabucco at the Chorégies d’Orange this summer where "Va pensiero" has always been a singalong. It will again be staged by Scarpitta.

And, quid pro quo, Scarpitta invited Muti’s daughter Chiara to Montpellier to stage Orfeo ed Euridice this past fall (yes, the Italian, not the French version), her debut as an opera director.

Enter another of the forces in Scarpitta’s artistic life: Georges Frêche, mayor of Montpellier from 1977 until 2004 when he became president of the Montpellier agglomeration and then president of the conseil régional de Languedoc-Rossillon until his death in October 2010. This remarkable man, prominent in the Socialist Party his entire life, gave Montpellier its current look, initiating major urbanization projects that have made Montpellier a model for the world. Among the most significant is a huge central plaza, the Place Comédie and Esplanade, with the fine old (1888) 1200 seat Opéra Comédie at one extreme and the ultra-modern, 2000 seat Théâtre Berlioz at the other. Scarpitta deems this expanse of enlightened urbanization a sleeping beauty, begging to be artistically fulfilled.

Evidently a passionate proponent of the arts Georges Frêche was also an advocate of making the arts accessible to a large public. He had his disciple in René Koering whom he advanced to Superintendent of Music for Montpellier in 2000. A golden era ensued that ultimately gave Jean Paul Scarpitta his theater, among many other accomplishments. Scarpitta staged the world premiere of Pergolesi’s never before performed Salustia, Hindemith’s lurid Sancta Susanna, Honneger’s Joan of Arc at the Stake, plus Offenbach’s never finished La Haine (here completed by composer Koering) with Depardieu and another of Scapitta’s fascinations, actress Fanny Ardant.

Koering named Scarpitta to “artist-in-residence” at OONM for 2006/07 thus signaling to the honorable Frêche that Scarpitta was artistically and politically his obvious successor. Scarpitta had moved in the François Mitterrand circles in Paris in the 1980’s (as did Françoise Sagan who became, by the way, an intimate friend of Scarpitta). Interestingly Mitterrand, France’s first socialist president, always kept his distance from Frêche who had been a fervent Maoist in the 1960’s and remained ever since a firebrand politician.

The death of Frêche in 2010 upended and ended the office of Superintendent of Music, its finances were made public (Montpellier’s daily newspaper Midi Libre reported that Koering had awarded himself an annual salary of 294,000 euros), its considerable deficits were questioned, and furthermore France’s Ministry of Culture had descended from Paris to insist that something be done about the quality of the chorus — not up to the standard of an opéra national!

Koering, then 70 years old, his artistic and political accomplishment enormous, stepped aside a year before his contract expired to make way for new energy — a team headed by Jean-Paul Scarpitta.

Rare and forgotten repertory has all but disappeared from Scarpitta’s personal theater, replaced by the grand repertory of heroines who are victims — Carmen, Manon, Violetta and particularly Mimi whom Scarpitta deems a saint who gains the veneration of all those who surround her. As a stage director Scarpitta describes his approach as instinctual rather than conceptual, allowing him to juxtapose the redemptive process effected by the sacrifices of these operatic heroines with his fascination for Baudelaire, a poet whose name he often mentioned during our lunch. In fact Baudelaire’s search in Les Fleurs du Mal for sublime beauty in crude reality is exactly matched in these four operas.

Scarpitta originally staged Mozart’s Don Giovanni in 2007 with France’s famed Le Concert Spiritual in the pit, this esteemed Baroque ensemble then in residence in Koering’s Montpellier. Most striking was the youth of the cast, and beyond that the perfection of the casting, each character beautifully defined physically, well endowed vocally and musically finished. The key to the staging was the hysterical laughter of Don Giovanni that ended the first act — a young man very unsure of himself, Scarpitta explained when I asked about the laughter. The uncertainties of youth were very present and made potent by fine singing. The death of the Don was but the catalyst of the consequent tragedies felt in all these young lives.

Les Noces de Figaro took us to another plain, that of luxury and elegance. Scarpitta’s friend, famous couturier Jean Paul Gaultier created the costumes that clothed the perfect cast. Again the crème de la crème of young singers who could have been cast because their bodies made high fashion design look like such, or these singers could have been cast because they were capable of highly refined lyricism. Scarpitta’s staging too was all about elegance, that restrained beauty inherent in minimal movement (this included several quite graceful full body falls). In spite of Figaro assuming the fetal position during Marcellina’s aria Mozart’s humanity was the casualty of the production.

Jean Paul Gaultier and Jean-Paul Scarpitta are both directors of the Carla Bruni-Sarkozy Foundation, an activity very much on Scarpitta’s mind. The foundation offers educational opportunities to academically talented, under-privileged youth, and stresses that the grants are made to youth both on the political right and left. In 2007 Scarpitta was one of 150 French intellectuals who signed a letter supporting Socialist Party candidate Ségolène Royal in her bid for the presidency of France won by Nicolas Sarkozy. On the other hand Scarpitta was one of 20 prominent French artists who signed a letter supporting Sarkozy in the 2012 presidential election.

As for nearly all the operas he has staged for Montpellier Scarpitta designed the set for Cosi fan tutte — a green floor and a blue wall. That is all. There is however no minimalism whatsoever in the pit. Conductors for the trilogy have been as young and talented as the cast. For Cosi it was English conductor Alexander Shelley who brought remarkable musical depth to this problematic Mozart opera. In fact this conductor made time stand still — the opera was not about its silly story, it was about the voices of youth, and Scarpitta’s staging left no emotive pulse of the music without an empathetic position. The splendid young cast abstractly danced to the music of this conductor.

Le Figaro rightly discerned that there was no humor in this Cosi, and went on to find a complete absence of stage direction in Scarpitta’s stripped down production, adding that the voices of the Fiordiligi and Dorabella were splendid if you did not have to look at the stage, and that the Despina was the only dramatically alive character on the stage. Le Monde rightly discerned that this was a staging of a légèreté galante (galant lightness), but meant that such an approach is hardly the current and appropriate politic for Cosi. And furthermore that the cast was uniformly mediocre, especially the Despina. Well, except the Dorabella who was magnificent, not to mention the equally wonderful violas of the orchestra, alto voices evidently on this critic’s mind.

An internet blogger correctly attributed Scarpitta’s dramaturgy to Robert Wilson (or “Bob” as he is known in France) and to Giorgio Strehler, suggesting that it is mere imitation. The venerated Italian metteur en scène Strehler was the first of Scarpitta’s theatrical fascinations, and through ballerina Ghislaine Thesmar he wangled an introduction. He then became part of Strehler’s Parisian cadre, observing this great director at work.

The European operatic avant garde has long been smitten with Texan Robert Wilson (Scarpitta now has Wilson’s, that is Bob’s gifted lighting designer Urs Schönebaum as part of his creative team). If Scarpitta’s stagings are homages to these two theatrical geniuses they are as well his homages to opera’s grand repertoire. This is Scarpitta’s style, based on his greatest need — to admire. This operatic minimalism, seen through Baudelaire’s filter of evil flowers gives Scarpitta his unique, and original directorial voice.

Scarpitta has not had good press, for example the Montpellier daily Midi Libre blindly repeated assertions by the chorus that he does not read music. I asked if he in fact does not read music. Of course he does, and plays the piano, one of the passions of his early youth. He does not read orchestral score, nor do I, nor I imagine do most of the choristers.

The Scarpitta artistic vision for Montpellier, and some of the guest conductors, like Riccardo Muti, and designers like Schönebaum have placed great pressures on the OONM salaires — the chorus, orchestra and the stagehands, the workers in the artistic trenches of the opera company. After the comfortable satisfactions of the Koering years they have not liked the Scarpitta challenges and have effected his removal from the direction of OONM.

Scarpitta has one final staging in his contract, Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle that will occur in fall 2014. Don Giovanni and Barbe-bleue are two masculine operatic signposts that hold great interest for Scarpitta. Like Giovanni, Barbe-bleue dares to show his inner self, his solitude, his sorrows, his difficulties with relationships. Scarpitta believes that the blood on Bartok’s stage is actually that of Bluebeard, oozing more each and every day. There is no doubt that it is Scarpitta’s blood to be spilled all over the stage this fall. And I believe he will have enjoyed every minute of his combats montpelliérains.

Scarpitta wishes his successor, Valérie Chevalier, success. He recognizes her very great experience will be quite useful as she confronts the enormous financial, artistic and political challenges facing OONM. In the wake of the Scarpitta difficulties for this current season the Regional Council, a supporter of Scarpitta, had diminished its contribution by 5 million euros (Georges Frêche had taken it to 9,5 million so it became 4 million). The president of the Montpellier agglomeration, Jean Pierre Moure, who removed Scarpitta from the OONM direction, stepped in with an additional 5 million to restore the budget to 24,000,000 euros. President Moure has made himself a very important patron of and participant in the affairs of the OONM.

It was a tense lunch at the Jardin des Cinq Sens, a Relais et Chateaux with its Michelin starred restaurant, Scarpitta’s residence when in Montpellier. He was on edge knowing that he is raw meat for journalists. I could not find a way to put him at ease and we never really connected during those two and one half hours. Well, maybe at the end we did — when we stood up he used his napkin to brush off the breadcrumbs that had fallen onto my shirtfront.

We met again after the late afternoon symphony concert at the Théâtre Berlioz. Young Alexander Shelley of the Scarpitta Cosi had conducted, slowly, very slowly Franck’s Symphony in D minor, and the principal cellist of the Orchestre National de Montpellier, Alexandre Dmitriev had performed Henri Dutilleux’s Tout un monde lointain, the title a verse from Baudelaire’s La Chevelure, and each of its five movements prescribed with verses pulled from Les Fleurs du Mal. Seated within sight of Scarpitta we could see he was transfixed (the man sitting next to me went to sleep). It was also quite apparent that some sections of the orchestra are in need of modernization.

No longer on edge, and walking on air after the Dutilleux, Scarpitta kissed the hand of my wife and recalled his trip through San Francisco, how he had admired the city on his way to Napa to visit his friend — yes, you guessed it — Francis Ford Coppola.

N.B. Michael Milenski resides in San Francisco in spring and fall, and in the south of France in winter and summer. His reviews of the Scarpitta Mozart/DaPonte operas are on Opera Today. This essay was compiled from articles in the French press, a lengthy statement by Jean-Paul Scarpitta on the website of the Carlo Bruni-Sarkozy Foundation, general information found on the web, and of course from his conversations with Mr. Scarpitta.

The Opéra de Marseille

Marseille woke up this past January 11 stunned to find itself number two on the New York Times list of 46 places you should visit in 2013 (Rio was number one, Paris just made the list at number 46).

Marseille has once again proved that making your way to the top is easy — spend some smart money! The Ville de Marseille boasts ten new spaces for the arts, among the more prominent the magnificent all-glass Museum of Civilizations and a gutsy new contemporary art venue in a huge graffiti covered old tobacco factory, not to overlook an old grain elevator on the docks that has become Le Silo, a high tech 1700 seat theater.

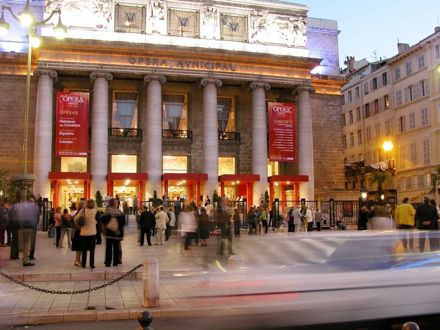

All this investment brought vibrant new spin to the Phoenician city (it’s that old) and propelled it to become the European Capital of Culture for 2013. Put this together with a snazzy new trolley system that descends to the Vieux Port (Old Port) with the Opéra just right there on Rue Molière and you have the Marseille that could be.

The Opéra de Marseille

The Opéra de Marseille

But sad to say Marseille has not invested recently is its opera house, badly in need of a well planned fire. Back in 1918 following the dress rehearsal of Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine a very efficient fire left only the outer walls and the peristyle [the columned classical porch] standing. It reopened in 1925 having eliminated its original Italian horseshoe shape in favor of a large first tier that offers, with the front orchestra the best seats in the house, and a plenitude of them. Though there exists a superb acoustic for opera and an absolutely splendid spectator-stage rapport the auditorium and its public areas are in dilapidated condition.

The decor is high art deco, think American movie palaces of the same era, though hopefully this is not the reason it is designated an historic monument. The peristyle is from 1787 and therefore proudly qualifies it as France’s second oldest opera palace. This stately colonnade with its splendid frieze has survived all earlier fires and surely could survive most any future fire — may we dream of a state-of-the-art twenty-first century hall and stage behind it.

The art deco proscenium and fire curtain

The art deco proscenium and fire curtain

Plus to be sure there is a second tier and above that there is the once infamous, very vocal amphithéâtre (the upper most gallery) where Maurice Xiberras, its current directeur général, likes to say he was taken at seven years of age by his grandparents to be smitten by opera. Most of all monsieur Xiberras wants us to understand that the Opéra de Marseille now strives to be populaire, that its supposed audience of longshoremen, cafe waiters and petits commerçants want nothing more than steak-frites and moules marinières and bel canto.

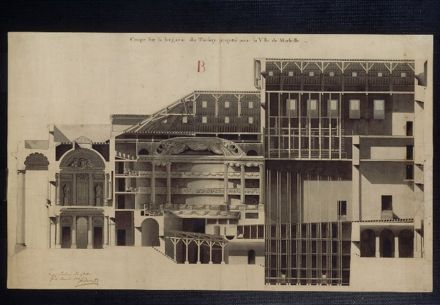

Cross section of Marseille 1787's Grand Théâtre

Cross section of Marseille 1787's Grand Théâtre

After all if you want cutting edge opera you can go one half hour up the road to the prestigious Aix Festival (but only in July), or cross the swampy Camargue in a bit more than an hour to Montpellier where the Opéra National de Montpellier oozes artistic pretension.

In Marseille there is the Théâtre National de Marseille and the Ballet National de Marseille, entities that are primarily funded by Paris and therefore subject to France’s national artistic aspirations. The Opéra de Marseille is decidedly not an opéra national, a position underlined firmly in 2011 when France’s then minister of culture, Frédéric Mitterand descended in an attempt to impose Parisian standards on Marseille’s opera. He suggested that the director of the Théâtre National de Marseille, Mme. Macha Makeïeff, replace Mr. Xiberras and offer classier programming.

Perhaps Mr. Mitterand was smarting because Marseille’s longtime mayor (since 1995) Jean-Claude Gaudin managed a coup d’état by thwarting Mr. Mitterand’s choice, Mme. Catherine Marnas, for the directorship of the La Criée (the théâtre national) and naming instead Mme. Makeïeff (born in Marseille) to the post. A force to be reckoned with the Honorable Gaudin in a grand coup de théâtre then promoted Mr. Xiberras (born in Marseille) and at that point artistic director, to general director of the Marseille Opera.

Marseille born conductor Reynald Giovaninetti was general director from 1971 to 1974 when the post was given to Toulouse born stage director Jacques Karpo. Both artists were well known to San Francisco Opera audiences in the ’70’s. Mo. Giovaninetti conducted Leontyne Price’s Manon Lescaut in 1974, and a triple bill that included Magda Olivera in Poulenc’s La Voix Humaine in 1979.

These were the halcyon years at San Francisco Opera when Kurt Herbert Adler was pushing operatic envelopes hard and fast, those of repertoire and production and singers. Jacques Karpo had come to San Francisco Opera as a lowly production assistant, then he graduated to assistant director and ultimately he staged Faust (1977) complete with a revolving disco ball (to catch the flashes of Marguerite’s jewels) plus Roberto Devereux (1979 — the one when Montserrat Caballé cancelled and it hasn’t been on the SFO stage since).

In 1974 young Karpo took everything he learned in San Francisco back to Marseille and made Marseille one of the most important stages in France for the next seventeen years. The impresario used colorful, vulgar language, chain smoked and died at 51 years of age. He is legend in Marseille, and it is legend that you couldn’t find a spare ticket to Marseille Opera during those years.

A hard act to follow. With its taste for the big time Marseille made Karpo’s assistant Élie Bankhalter its general director (1991-1997). Mr. Bankhalter now offers training in motivational speaking on his website where he boasts associations with just about every important singer of the ‘90‘s you can think of, many of whom actually appeared on the Marseille stage in signature roles, i.e. the most standard repertory.

It was time for change.

In a swing to exploring repertoire instead of stars its next director (1997-2001), Jean Louis Pujol flamed out with a season based entirely on Oriental legends, including an operatic setting of Racine’s Bérénice [queen of Palestine] by Massenet’s student Albéric Magnard, premiered in 1911, and then rediscovered by Mr. Pujol. Not to overlook other Pujol resurrections — Mârouf, savetier du Caire by Henri Rabaud (1914 premiere at the Opéra Comique, picked up by the Met in 1917), and L'Atlantide (1954) by Henri Tomasi (born in Marseille).

Renée Auphan, the Opéra de Marseille’s born-in-Marseille general director from 2001 to 2008 one-upped Mr. Pujol. She programmed Tomasi’s Sampiero Corsu (1956) that was not only composed by the Marseille native, but it’s protagonist Sampiero recreated that splendid moment of Corsican history when he strangled his wife right there in Marseille.

Mme. Auphan had been director of both the Lausanne and Geneva operas before returning to Marseille. Surely her finest hour was Marius et Fanny, music by Vladimir Cosma, a film composer best known for Diva (1981). Marius et Fanny is a love story construed from three plays about Marseille by Marcel Pagnol, the born-in-Marseille beloved-by-Marseille novelist who wrote Manon des Sources. The opera takes place right on the Vieux Port. Its characters, longshoremen, cafe waiters and petits negociants included Roberto Alagna and Angela Gheorghiu in happier days.

|

|

Well, Mme. Auphan is a hard act to follow. This able stage director turned soprano turned directeur général imposed solid vocal standards and solid if mostly uninspired production values. Mr. Xiberras, Mme. Auphan’s assistant during her entire tenure, is cut from the same cloth. Though he has ventured from Pagnol’s Italian immigrants on the Vieux Port to the Italian immigrants of Menotti’s New York tenements with The Saint of Bleecker Street. And of course not to be outdone by la Auphan he has commissioned film composer Jean Claude Petit to provide music for a libretto based on Merimée’s Corsican tale Colomba. Mr. Petit provided the music for the famous film of Pagnol's Manon des Source (1986) and was the arranger for Billy Vaughn’s best selling LP “Greatest Country Hits” back in the ’70’s.

Born-in-Marseille metteur en scène Charles Roubaud will stage Colomba (2014). Jacques Karpo gave the very young Roubaud his first job, staging Massenet’s Don Quixote back in the 1980’s, a production that soon made its way to San Francisco (1990) further enriching the Jacques Karpo legacy in that city. Since the Don Quichotte Charles Roubaud has created more than twenty productions for the Marseille stage, including the above mentioned Bérénice. This past January he restaged his 2003 production of Elektra to solid critical appreciation.

Just now, June 15 - 23, Mr. Roubaud is creating a new production of Massenet’s forgotten Cléopâtre for the Marseille stage with the same designers, Emmanuele Favre (scenery) and Katia Duflot (costumes) as the Elektra. Mme. Duflot is another protégé of the Jacques Karpo era who now heads the Opera de Marseille’s prolific and ubiquitous atelier couture.

July 12 and July 15 Roberto Alagna and Béatrice Uria-Monzon sing Aeneas and Didone in Berlioz’ Les Troyens (concert performance) conducted by Los Angeles born Lawrence Foster, the recently appointed music director of the Opéra de Marseille — maybe its first since Reynald Giovaninetti. Maestro Foster, former music director of the operas of Monte Carlo, Barcelona and Los Angeles, is a refugee from the recent brutal reshuffling of forces at the Opéra National de Montpellier.

The Opéra de Marseille operates on a budget of 16,000,000 euros. The current seasons is four or five performances each of seven operas, thirteen orchestra concerts (most at the Opéra, others in various venues), plus a number of recitals and chamber music concerts. The concert Les Troyens is part of the Marseille’s 2013 Capital of Culture initiative. The Opéra de Marseille seats 1800.

To read my reviews of various operas in this article go to this site's Review Archives. Operas are listed alphabetically by name.

Opera House Fires in the South of France

The worst enemy of an opera house is fire. These dramatic fires are sometimes laden with tragic irony when gruesome death greets those who have come seeking pleasure. In 1881 at the Théâtre Royale in Nice an eager audience awaited Bianca Donadio as Lucia de Lammermoor. The first act curtain fell not to brightly illuminated scenery but to a raging fire on stage that quickly engulfed the auditorium. Fifty-nine bodies of an estimated 200-400 victims were recovered, mostly those sitting in the poulailler (pigeon roost).

In recent history a sans abri in Frankfurt found his way onto the opera's cold stage and built a small fire to warm himself. In Venice a behind schedule electrical contractor contrived a small fire to gain a reprieve, an unidentified cause provoked a fire that devastated Barcelona's Liceu. Perhaps the best friends of these old opera houses were their fires. From destruction comes renewal as the outdated stage houses of the Liceu, La Fenice and Frankfort are now state-of-the-art spaces ready to exploit the latest advances in scenic technology. The meticulously restored auditoriums in Venice and Barcelona belie the presence of modern acoustical materials, ventilation and creature comforts.

The paper, wood and cloth, the flammable materials of olden-day scenery were illuminated by candles or oil lamps, the open flame's light reflected through vials of red wine to create emotional red hues. Yet these obviously dangerous light sources were far safer than the gas lights of late nineteen century theaters that offered easily adjusted lighting and considerable effect. These lights required intricate piping to deliver their explosive fuel. It was such an accident that destroyed Nice's old theater, its stage and auditorium scaffoldings constructed entirely of wood.

The new Opéra de Nice was designed in stone and steel by Niçoise architect FranÁois Aune, a student of Gustave Eiffel, the famous pioneer of steel structure. Eiffel himself had engineered the dome of Nice's Observatoire du Mont Gros, a building he designed in collaboration with Charles Garnier, the dernier cri of Second Empire civic architecture. Garnier had made his reputation by winning the 1861 competition for the design of the new Opéra in Paris (now named the Palais Garnier perhaps to distinguish it from Monaco's Salle Garnier, Garnier's 1879 version of a really truly luxurious theater for the rich).

France's historically important seaport city Toulon is of course not without an imposing opera house. Its current one was designed in the late 1850's and built between 1860 and 1862. Its history is sketchy and controversial. Reliable sources point to Toulon born Léon Feuchère as its creator, the architect who gave Nimes its beautiful Prefecture (and his name to the Avenue Feuchère), though some sources attribute its elaborate neo-Louis XIV inspired design to the as-yet-unknown Garnier himself. Malicious sources intimate that Garnier elaborated Feuchère's designs for the Paris competition thus making Toulon's sumptuous Opéra the model for Paris'.

The cornerstone of Marseille's Opéra was laid in 1786, though that stone is most of what there is left of the original theater. Marseille thereby joined Bordeaux as the first cities in all France to boast their Opéras. The grand old Marseille theater was finally gutted by flames after a rehearsal of Meyerbeer's L'Africanne in 1919, Bordeaux's old theater long since replaced by an impressive Garnier designed opera palace. The renewed Opéra de Marseille reopened in 1924, and now longs for a catastrophe to provoke it to be brought to twenty-first century standards.

Human ingenuity is also a great friend to opera houses. Montpellier achieved some of the world's finest urban renewal, the centerpiece of which is a brand new, 2000 seat opera house, the Salle Berlioz in its monumental Corum. This magnificent pink marble theater was designed by Strasbourg architect Claude Vasconi, the mastermind of Les Halles Forum in Paris. Though at the very top of the ingenuity list is Jean Nouvel's Opéra de Lyon. This progressive city did not invoke catastrophe to destroy its out-of-date theater, it simply brought in a famous architect who built a new theater right on top of the old one! It is worth a trip to Lyon just to see this 1830 neo-classic structure crowned by a sleek quonset hut, its gutted interior replaced by molded black plastic, and named what else but the Opéra Nouvel.

Raoul Mille in the first volume of his Ma Riviera, Chroniques vividly describes the fire at the Opéra de Nice, and the sang froid of the diva Bianca Donadio who emerged through the flames holding her habilleuse in her arms. In this same volume Mr. Mille also recounts the realization of the last dream of Frankfurt banker Louis-Raphael Bischoffsheim, the building of the Garnier designed Observatoire du Mont Gros.