2023 CA/US reviews:

Carmen in San Francisco (November 19, 2024)

Everest in San Francisco (November 10, 2024)

Tristan and Isolde in San Francisco (October 25, 2024)

The Handmaid's Tale in San Francisco (September 26, 2024)

Un ballo in maschera in San Francisco (September 24, 2024)

Partenope in San Francisco (June 15, 2024)

Erwartung at San Francisco Symphony (June 8, 2024)

Innocence in San Francisco (June 7, 2024)

Die Zauberflöte in San Francisco (June 4, 2024)

Florencia en el Amazonas at Opera San Jose (April 20, 2024)

"Birds and Balls" at SF's Opera Parallele (April 6, 2024)

Carmen in San Francisco

Francesca Zambello’s 2006 Covent Garden Carmen rehashed once again by San Francisco Opera. This time with French mezzo-soprano Eve-Maud Hubeaux in the title role.

In 2017 alone Mme. Hubeaux transformed herself from Thibaud in Don Carlo at the Paris Opera into Eboli at the Lyon Opera where she was lauded (by me) for the easy energy she exuded from her wheelchair (it was a weird concept). Since then she has exploded into Amneris at the Salzburg Festival, Eboli in Vienna, Hamlet’s mother at the Paris Opera, where upcoming is Fricka in Das Reingold. Not to mention Carmen in the Calixto Bieito production (high concept) of the Vienna State Opera, upcoming is Carmen in the Dimitri Tcherniakov production at Brussel’s La Monnaie echoing his 2017 Aix Festival production (very high concept).

Mme. Hubeaux (lead photo) did not fare so well in Mme. Zambello’s wannabe slick, music hall concept production that pulled every trick in the book to make Bizet’s brutal, game changing opera into a slight, easy going, bloodless entertainment (talk about weird concepts). Though there were embellishments this time around. Significantly Micaela did not shower streamers and confetti from above onto the dead Carmen and distraught Jose in the opera’s final moments.

La Hubeaux did bring an easy energy to her Carmen, particularly vocally. She is a fine singer, endowed with a rich voice that she uses with great intelligence. It was a well sung, vocally nuanced Carmen. It however did not find, and could not have found the femme fatale allure that enraptured Jose, nor capture the ferocity of Carmen’s spirit of independence, nor feel her sense of doom or her sense of the senselessness of her life. Perhaps these attributes can be spelled out more easily in successful concept productions.

It remained a well sung exposition of the Carmen monuments.

Carmen’s anthesis, Micaela, was sung by British soprano Louise Alder. A performer of great poise, she wore Micaela’s blue dress, bathed in Act III’s blue light with knowing aplomb. She possesses a sizable lyric voice that explodes with thrilling overtones in its upper registers. Mme. Alder relied on a well-founded Mozartian artistry (Vienna, Munich, Glyndebourne) to create a Micaela abounding in musical and vocal subtleties, her third act “Je dis” enthralling us with its perfection, belying the innocence and simplicity of its intention.

Louise Alder as Micaela, Johnathan Tetelmann as Jose in Act 1

Louise Alder as Micaela, Johnathan Tetelmann as Jose in Act 1

American bass-baritone Christian Van Horn created a monumental Escamillo. Of powerful voice embodied in a huge persona (a signature role is the Hoffman villains). He made his Act II entrance on a real horse — one hand firmly attached to the saddle horn — and summarily blew us away with his Toreador Song. In Act III his larger-than-life stature and presence became a bit of a problem when he gamely attempted a knife fight with Jose. No one got hurt.

Carmen’s enflamed lover Jose was enacted by American tenor of Chilean descent Jonathan Tetelmann (lead photo). Aspiring to assume tenorissimo stature Mr. Tetelmann well embodied Bizet’s Jose physically as well as vocally, the young Andalusian needing both delicate sensitivity as well as grandiose passion. Tetelmann relished sailing up to his high notes in powerful tenor sound, beautifully intoning at the end his final shouts of grief, yet finding the control of voice to pull back from the climactic fortes of his Act II Flower Song to heartfelt, pathetic softer tones. The Tetelmann Jose approached that of a total performance in this evening of purely singerly performances.

The smaller roles were undertaken by current and former Merola and Adler Fellows to varying degrees of effectiveness.

The Zambello production was staged by Anna Maria Bruzzese, an Italian choreographer and stage director. Added — if I am not mistaken — to the SFO 2019 edition was a complex Act I changing of the guard enacted solely by Sevillian street urchins, here the San Francisco Boys Chorus and the San Francisco Girls Chorus. It got a bit scary, musically, but it was staging virtuosity indeed. Added also was the ballet executed at the opening of the Act II during the Frasquita/Mercedes/Carmen trio, flashily executed, à la grand opera balletic protocol [Carmen is an opéra comique], by the nine dancers of the San Francisco Opera Ballet.

Christian Van Horn as Escamillo, Eve-Maud Hubeaux as Carmen, Act IV

Christian Van Horn as Escamillo, Eve-Maud Hubeaux as Carmen, Act IV

Though Mme. Bruzzese eschewed restoring the Act I chickens and dogs from the original Covent Garden production she overplayed the live horse trick by having Carmen arrive at the Act IV bull ring atop the horse, by now surely a very tired horse.

The conductor was Houston Opera protegé Benjamin Manis who established a quite firm, super fast beat for the overture, gracefully effected by the San Francisco Opera Orchestra. He then oversaw a leaden Act I. The dancers kept up with the fast music that opens Act II, the maestro gave Escamillo ample rein for his blockbuster aria. The Act III flute/harp/clarinet idyll was rushed, and perfunctory, though the maestro indulged in the exquisite perfection of Micaela's blockbuster aria. The Act IV chorus and procession was at breakneck speed.

The excellent lighting was effected by Justin A. Partier.

War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, California, November 19, 2024. All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera

Everest by San Francisco's Opera Parallèle

San Francisco’s alternative opera company has just now revived its 2021 production of Everest, a 2015 Dallas Opera commission about climbers on Mount Everest, here reimagined as a graphic novel (comic book format) cast onto a planetarium dome.

Unlike San Francisco’s other opera company Opera Parallèle is about production. Moving from performing space to performing space it delights its audiences with staging concepts and solutions that challenge, amuse and amaze our minds and spirits. Even so Everest at the California Academy of Sciences Planetarium was a bit of a stretch.

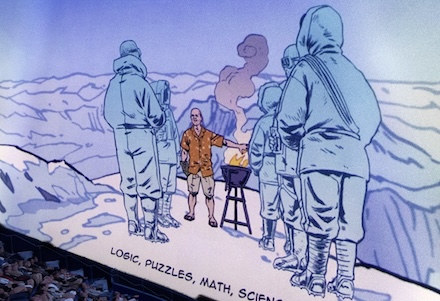

Though we may have imagined photographic images of the daunting atmospheres of this monstrous magnificent mountain in such an immersive, planetarium enclosure we were confronted with crudely drawn abstractions of the mountain, and comic book renderings of the human forms of the opera’s actors. There were no live performers, it was an entirely recorded experience.

Rob Hall (lead photo on left, Doug Hansen on right) was a New Zealand mountaineer who together with his wife Jan Arnold led Everest expeditions. Jan, pregnant, stayed behind for this 1996 expedition, Rob led two amateur climbers on this ill-fated ascent. Doug Hansen, a mailman, achieved the summit, then perished with Rob. Beck Weathers, a Texas pathologist, stranded on Everest’s “balcony” (1300 feet below the summit) staggered back to the base camp.

Doug Hansen struggling to reach the Everest summit

Doug Hansen struggling to reach the Everest summit

The opera is a memorial for these three men, and all of the twelve climbers who died during the 1996 Everest climbing season, plus maybe the twenty-three fatalities of the 2015 season, and probably the sixteen fatalities of the 2014 season, their faded images often floating onto the dome — anyway there were many names projected onto the dome in the final moments of the 68 minute opera.

Everest as a graphic novel for the local planetarium was conceived and directed by Brian Staufenbiel, Opera Parallèle’s creative director. Most likely it was a Covid-shutdown-era project when we were closeted in our respective creative spaces, a project that could be realized without bringing together the expansive resources of an opera production into the infectious confines of a theater. Plus it was hardly an unreasonable step, or maybe it was a mighty leap, to envision these well-storied, ill-fated climbers as super heroes achieving their impossible feats in the solitary confines of a comic book.

And where else than to imagine these feats taking place in the cosmic expanses of a planetarium.

Conductor Nicole Paiement, Opera Parallèle’s founder, had conducted the sizable orchestral resources (triple winds, full strings, much percussion) at the opera’s Dallas premiere. For the planetarium recording these forces were rendered in digital approximation by the opera’s British composer Joby Talbot working in London together with sound engineer Magnus Green, molded from afar by Mme. Paiement. The voices were individually recorded in Oakland, then it was all mixed together by sound designer Miles Lassi at Oakland's Skyline Studios.

The Opera Parallèle Everest production itself was a feat that dwarfed the story it told.

The Everest libretto was created by Gene Scheer, well known for his collaborations with Jake Hegge and for a thwarted commission at San Francisco Opera for Cold Mountain (with composer Jennifer Higdon). The commission was subsequently assumed by Santa Fe Opera (et al), its premiere occurred the same year as Everest, relevant because in Cold Mountain Scheer was confronted with creating lines in the Appalachian accent. In Everest the Texas pathologist was sung in a definitive, jarring Southern accent.

Rather than portray Everest’s climbers in cosmic, heroic terms, Scheer created characters who were quite attached to their very basic human needs and feelings — an insecure postman, a depressive pathologist, a stoically sentimental leader. There was little heroism in Everest.

Beck Weathers imagines himself back in Texas, with phantom images of dead Everest climbers.

Beck Weathers imagines himself back in Texas, with phantom images of dead Everest climbers.

Opera Parallèle assembled an impressive cast for the recording of the opera, notably tenor Nathan Granner as the expedition leader Rob Hall and mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke as his wife Jan Arnold. The Texas pathologist Beck Williams was sung by Tennessee born bass Kevin Burdette, the postal worker Doug Hansen was sung by baritone Hadleigh Adams, Kevin Burdette’s daughter Meg was sung by soprano Charlotte Fanvu.

The animation was created by David Murakami, with illustrations by Mark Simmons. The sound design for the planetarium was effected by Miles Lassi.

California Academy of Science, San Francisco, California. November 10, 2024. All photos copyright Scott Wall, courtesy of Opera Parallèle.

Tristan and Isolde in San Francisco

In the 1870’s Richard Wagner built a special theater for his operas, a theater where the words of his poems might flow clearly from the stage into the hall. One hundred years later supertitles came into being, quickly making Wagner’s dream of reviving Greek tragedy a reality —supertitles actually allow intoned words to be understood, not to be simply felt.

While Wagner’s Bayreuth Festival famously indulges itself in the latest dramaturgical trends it does not avail itself of this more recent development. Supertitles, it should be argued, are critical to the appreciation of Wagner’s poems, surely the bedrock of his theater. Thus the Festspielhaus audiences at the splendid new Bayreuth Tristan this past summer were deprived of the intricacies, the complexities, and the subtleties of Wagner’s quite magnificent poem.

But not we San Franciscans who just now participated word-for-word in San Francisco Opera’s splendid account of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, a work reputed to be the operatic apotheosis of Romanticism. Conductor Eun Sun Kim assumed the production’s rhetorical stance in the un-staged overture. Avoiding a musical sweep, she carefully stated the famed initial, questioning chord, insisted on the overture’s intricate phrasing, then steadily built to the opera’s strategically recurrent mordent (note above, note, note below, note) that is Tristan and Isolde’s chain link of connection (lead photo). And finally, with Wagner, let it disappear into the unfolding tragedy.

The poem is a masterfully constructed opera libretto within the Wagnerian poetic. It is a treatise on the fatality of love and the philosophical impossibility of its fulfillment, told by contrasting light with darkness, day with night, this thesis expounded not without the complications of human loyalties. Obviously Tristan is not the same opera it was at its premiere one hundred fifty years ago, having since been subjected to the critical analyses accorded such masterpieces.

Scottish stage director Paul Curran however did not burden his production with any overriding critical concept, or any concept at all for that matter, allowing the words of his actors to determine where, how and when they moved, like in a sort of real life naturalism. Mr. Curran always placed his actors across the front of the stage facing us, where they sang Wagner’s poem exactly as it was projected on a screen just above the stage. It was much like a semi-staged opera.

The physical production, by British designer Robert Innes Hopkins, came from Venice’s Teatro La Fenice where it was previously staged by Mr. Curran. It consisted of two, rather small reversible wall units, a wooden trellis, a tree and a chair (at a cost of maybe 20 cents in operatic dollars). The lighting, by U.S. designer David Martin Jacques, was crudely effected.

Thus the production, or lack of, left Wagner’s masterpiece to Maestro Kim and the San Francisco Opera orchestra who rose magnificently to the occasion with the maestra’s usual vivid presence, the sound at one with the words that flowed clearly and easily from the stage. Orchestrally it was a measured, precise reading of Wagner’s meticulously nuanced score that could have seemed stolidly procedural had we not carefully followed the words of the poem. As it was we were totally immersed in Wagner’s complex, timeless, awesome gesamtkunstwerk soundscapes.

Anikka Schlicht as Brangäne, Anja Kampe as Isolde

Anikka Schlicht as Brangäne, Anja Kampe as Isolde

The exemplary cast as well rose to the occasion. Tristan was sung by New Zealand tenor Simon O’Neill, a singer whose voice exhibits a character tenor sound to current ears, but a sound that evokes the storied Tristans of San Francisco Opera’s earlier eras, notably Wolfgang Windgassen in 1970. Mr. O’Neill has solid technique that he employed to maximum effect in his Act III soliloquy, electrifying in its nuanced delivery, carefully paced by the maestra to find its two shattering conclusions.

Isolde was sung by German soprano Anja Kampe who looks very much the Irish maid of the Tristan legend. Mme. Kampe is a recognized Isolde having performed the role on the major German stages, though in this production she did not find the heroic and philosophic stature usually ascribed to Isolde. Never losing her beautifully focused, truly heroic tone she remained a solidly voiced heroine through her movingly straightforward “Liebestod” — though she skipped over Wagner’s final mordent as she soared to her long awaited union with Tristan.

Kwangchul Youn as King Marke (standing), Simon O'Neill as Tristan

Kwangchul Youn as King Marke (standing), Simon O'Neill as Tristan

Marke was sung by Korean bass Kwangchul Youn. Miscast last spring as Zarastro in The Magic Flute, he now shone with black voiced authority, exuding his profound suffering at Tristan’s betrayal. His famed Act II soliloquy was solemnly stated, without overt art song affect, the beat of his voice echoing his heavy heart as the scene was perfectly paced by the maestra. At the end of the opera he fully embodied the humanity that mourned the Romantic tragedy of the lovers.

Brangäne was sung by German mezzo soprano Annika Schlicht. Of similar bright voice to Isolde she was as much Isolde’s alter-ego as she was Isolde’s maid. The opera’s opening scene was the sparring of two shöne madchen in this production’s demystification of the Tristan legend, not a scene of an interior, personal, philosophic, heroic battle.

Kurvenal was sung by Austrian baritone Wolfgang Koch. Mr. Koch is of a quite beautiful, Italianate voice belying his scruffy persona in this production. The role was greatly diminished from its often heroic display of unwavering fealty. Of note was the offstage voice of the sailer’s song that opens the opera, sung by former Adler Christopher Oglesby (though he was on-stage). As well Mr. Oglesby made great impression as Act III’s on-stage shepherd who mimed playing Wagner’s exquisite English horn solo. Melot was sung by Adler Fellow Thomas Kinch.

War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, October 25, 2024. All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera.

The Handmaid's Tale in San Francisco

Feminist dystopian opera. The Royal Danish Opera’s 2022 production of The Handmaid’s Tale found fertile field in San Francisco!

In short Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel made into an opera (though first it was a movie, and later it became a television series) that imagines a world in which the barren wives of its male leaders are provided children by fertile women who are enslaved for such purpose. Its then precedent was the 1979 formation of Iran as an Islam-centric state, its current precedent is the U.S. Republican ticket (echoing Republican ideals that were already fomenting in the 1960’s, noted by Margaret Atwood).

Though Toronto based Mme. Atwood sets her novel in the United States sometime in the 2190’s, Danish composer Paul Ruders grabbed onto the novel as a great idea for an opera right now. In 1994 he enlisted British actor/writer Paul Bentley (High Septon in Game of Thrones) to create a libretto. The premiere took place in Copenhagen in 2000, (in Danish), then traveled to London's English National Opera (2003) and then on to Toronto (2004). Meanwhile the Minnesota Opera gave the opera its U.S. premiere in 2004 in its own production. The ENO mounted its own production in 2022. Boston Lyric Opera mounted its own production in 2019. The Royal Danish Opera created a new production in 2022 that has now traveled to San Francisco.

Prestigious directors and designers have associated themselves with the opera over the years, lending it stature. If nothing else it is an important political statement, offering a ritualistic exposition of feminist issues, and a caricatured exposition of certain political goals. The opera’s U.S. setting underscores the worldwide and domestic perception that the U.S. is the world’s bogeyman.

The Handmaid’s Tale is an opera to be endured, a ritual where you may expiate at least some of the social, moral and personal pain that afflicts you — those of you who stayed until the end that is. There was noticeable attrition after the intermission of the performance I attended. Those that stayed at the end leapt to their feet.

Sarah Cambidge as Aunt Lydia, Irene Roberts (front row, extreme right) as the Handmaiden

Sarah Cambidge as Aunt Lydia, Irene Roberts (front row, extreme right) as the Handmaiden

There was much red in the clothing of women attendees at that performance, evidence of the pop solidarity of women with Mme. Atwood’s red robed handmaidens, who assembled from time to time on the War Memorial Stage, and graphically suffering (sometimes at the hands, a vista, of male gynecologists). Intermission comments overheard in the men’s room were groans of the word “heavy!”

Having endured such an evening at the War Memorial Opera House why would anyone want to go back!

San Francisco gathered many prestigious artists to sing this new Danish production in English. The primary role is a character known as Offred (I.e. assigned to Fred, who was the main male leader). Offred was sung by Irene Roberts, a veteran of many roles at SF Opera, and primarily known for her Wagnerian roles on prestigious European stages. The Ruders opera is narrative rather than lyric, Mme. Roberts delivered it beautifully — a tour de force of memory. At the bows Mme Roberts literally dove into the prompter’s box to thank the unnamed prompter.

The Offred Commander, whose name is surely Fred, was richly sung by Canadian baritone John Relyea, another singer with prestigious European credits. In The Handmaid’s Tale he proves to be sterile, thus his chauffeur Nick, sung by tenor Brenton Ryan had to strip and step in. Fred’s barren wife Serena Joy was played and richly sung by mezzo soprano Lindsay Ammann. Offred had a double to portray her life before she was forced into sexual slavery, and a husband Luke as well, plus a child (proving she was fertile), roles played by French mezzo soprano Simone McIntosh and tenor Christopher Oglesby, their child did not sing, thus is unnamed (see lead photo, the Handmaid looking on). Canadian soprano Sarah Cambidge sang Aunt Lydia, the overseer of the handmaidens, in high tessitura that exacerbated my patience for the domination of female voices.

John Relyea as Fred, the Commander, Lindsay Ammann as Serena Joy, his wife (in blue), Irene Roberts as the Handmaiden (in red)

John Relyea as Fred, the Commander, Lindsay Ammann as Serena Joy, his wife (in blue), Irene Roberts as the Handmaiden (in red)

There are 29 named roles in The Handmaid’s Tale, plus chorus, dancers and 22 supernumeraries. The San Francisco Opera Orchestra was conducted by Karen Kamensek who magisterially presided over the long narrations emanating from the stage, her orchestra in outraged sympathy (tone clusters moving melodically when it was not playing caricatures of hymns).

The production was by British stage director John Fulljames, staged in San Francisco by Lucy Bradley. British set designer Chloe Lamford created an appropriately fascistic architectural box in which hung sacrificial handmaidens, and often the Eye of Horus (the Masonic [male] Eye) that watched over every moment of this imagined world.

War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, California, September 26, 2024.

All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of Ssn Francisco Opera.

Un ballo in maschera in San Francisco

Where were the censors who once plagued Verdi’s Ballo just now when they should have saved us from an abysmal staging at San Francisco Opera!

It was the 2016 production from the Teatro di Roma directed by someone named Leo Muscato. In addition to writing and staging many plays over the last 20 or so years Mr. Muscato has found time to stage many operas, in many Italian cities, large and small.

At least it was not another rehash of San Francisco Opera’s old 1977 production (last seen in 2013) designed by John Conklin and restaged by many different directors over the years.

Verdi’s original Ballo was titled Gustavo III. But censors objected to putting a monarch (of any era) on the stage, much less murdering him. So the opera became Una vendetta in domino set in provincial Poland. Finally it became Un ballo in maschera, though it was now set in colonial Boston. Regicide was obviously a hot topic at the time, what is now Italy dealing with the Hapsburgs, the Bourbons, the House of Savoy and the Pontiff, not to mention that everyone knows what happened to the Capetians.

The premiere of Ballo was in Rome in 1859 — as the Boston Ballo! (this version was once actually seen here in San Francisco!). Nowadays Ballo is usually set in Stockholm. Interestingly, the Swedish crown was once an important player in European politics, both in pre-revolutionary France during Ballo’s king Gustavo III’s reign, and in the checkerboard of early-unification Italy under the House of Savoy (1861).

Whatever political edge Verdi’s late middle period operas (Ballo, Forza, Boccanegra) may have had, or still have is ignored by stage director Leo Muscato. Verdi’s Ballo libretto, made by Antonio Somma (the librettist as well for Verdi’s Re Lear) is based on French playwright Eugène Scribe’s original 1833 Le Bal Masqué libretto (for composer Daniel Auber) that made this bit of history (the assassination of Gustavo) into a classic melodrama — Amelia, an invented character, as a fallen woman.

Lianna Haroutounian as Amelia in Act II

Lianna Haroutounian as Amelia in Act II

It was murky storytelling, more suggestive than apparent, particularly in the Act II setting (a field outside town where Amelia is to pick a magical herb), where Gustavo and Amelia would declare their love. It was but a light show of rainbow colors on raging vapors, nothing more, hardly magical.

Verdi created very beautiful music for Un ballo in maschera, much of it derivative of his famed early middle period operas, but also looking forward to his Don Carlos with its extensive use of the minor second (Renato’s weeping). San Francisco Opera Music Director Eun Sun Kim held the San Francisco Opera Orchestra in very firm control, encouraging always the quite beautiful voices on stage to pour out their troubled words, carefully unleashing her orchestra from time to time to underscore Verdi’s grandiose, operatic passions.

Conductor Kim’s second act was musically exquisite, carefully building to the climactic declaration of love — but the declaration itself disappeared into the random colors of the light show. Adding to the subversive staging suffered by the conductor was the melodramatic lighting — sudden intensities, momentary darkness, etc. The imported, Italian, Muscato production rendered Eun Sun Kim’s beautifully conducted Ballo slick rather than felt.

The role of Gustavo (aka Ricardo) as sung by tenor Michael Fabiano (lead photo, with Ulrica) was a tour de force, this excellent singer held full voice through three punishing acts, offering finally an exquisitely phrased death scene. Though Mr. Fabiano has a quite beautiful voice, it does not possess the Italianate character that would have more fully created his musical character. Mr. Fabiano was perhaps directed to vividly act out his role. It read, however, as stock, over-acting.

Amelia was sung by Armenian soprano Lianna Haroutounian. She too possesses a quite beautiful voice, she rendered her Amelia in exquisite phrasing, and acted in reserved, operatic stances that were indeed appealing. Though her voice is more adapted to the Puccini heroines she often plays, her Amelia was convincingly achieved.

Jongwon Han as Count Horn, Adam Lau as Count Ribbing, Amartuvshin Enkhbat as Renato

Jongwon Han as Count Horn, Adam Lau as Count Ribbing, Amartuvshin Enkhbat as Renato

Gustavo’s friend Renato was sung by Mongolian baritone Amartuvshin Enkhbat. Mr. Enkhbat is a true Verdi baritone of beautiful voice. He too found synchronicity with conductor Kim to deliver an excellent, quite singerly performance though his Italianate stage presence seemed a bit out of place on the War Memorial stage — his career is exclusively in Italian theaters.

Oscar was sung by Chinese soprano Mei Gui Zhang in a quite charming performance of a role that is usually a star turn. The cameo role of Ulrica was sung by famed Romanian mezzo Judit Kutasi (lead photo, with Gustavo). She was in excellent voice, holding the stage appropriately as a true Verdi mezzo.

The supporting players were well cast. With the exception of Adam Lau as Count Ribbing, Jongwon Han as Count Horn, Samuel Kidd as Silvano, and Thomas Kinch as Amelia’s servant are all current Adler Fellows.

This splendid cast deserved a real production.

War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, CA., September 24, 2024.

All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera

Partenope in San Francisco

Unlike many of the recycled productions at San Francisco Opera, Christopher Alden’s famed 2008 production of Handel’s comedy Partenope, just now on the War Memorial stage, has lost none of its original freshness.

Credit the superlative conducting of English maestro Christopher Moulds who made the San Francisco Opera Orchestra into a rich and magnificent Handelian ensemble, its 2 horns in flawless heroic battle, its strings (8/6/6/4/2) in exquisite precision, its continuo in indefatigable support of the lengthy recitatives. The maestro led the singers into the ecstasies of the Handelian fioratura, the depths of despair, the furies of deception, etc. — the extended parade of arias that make 18th century opera.

Credit the superlative casting, including two important European singers in their American debuts — French soprano Julie Fuchs as Partenope and Italian countertenor Carlo Vistoli as her erstwhile lover Arsace. Interestingly, there were two carryovers from San Francisco Opera’s first reprise (2014) of this English National Opera production — mezzo soprano Daniela Mack as Rosmira, Queen of Persia, disguised as Eurimene (a faux suitor of Partenope), and tenor Alek Shrader as Emilio, a general from Cumae (a neighboring princedom), who demands Partenope’s hand.

Not to mention American countertenor Nicholas Tamagna as Armindo, who finally wins Partenope’s hand, and baritone Hadleigh Adams as Partenope's factotum Ormonte, who executed some impressive, real ballet steps.

That’s it — no chorus or supernumeraries!

Countertenor artistry has advanced mightily in recent years, making it current performance practice to cast males in male roles, adding the verisimilitude that voids all suspension of belief. Messieurs Vistoli and Tamagna both possess leading man auras, both exude great charm as well as sing in the alto range with ease and true beauty of voice. Both easily meet the physical theater demands of the Alden production.

Mme. Mack and Mr. Shrader (Adler Fellows at SF Opera in 2008/9) have gained artistic maturity since creating their roles in SF Opera’s 2014 Partenope. Both now command the stage unequivocally, sing with power and pizazz, and leave no Handel or Alden witticism undiscovered, Mr. Shrader enacting the American dada artist and photographer Man Ray with infectious enthusiasm, Mme. Mack raging with jealousy at Arsace’s infatuation with Partenope.

Julie Fuchs as Partenope, Carlo Vistoli as Arsace, Nicholas Tamagna as Armindo, Hadleigh Adams as Ormmonte, Daniela Mack as Rosmira

Julie Fuchs as Partenope, Carlo Vistoli as Arsace, Nicholas Tamagna as Armindo, Hadleigh Adams as Ormmonte, Daniela Mack as Rosmira

Julie Fuchs as Partenope, Carlo Vistoli as Arsace, Nicholas Tamagna as Armindo, Hadleigh Adams as Ormmonte, Daniela Mack as Rosmira

Julie Fuchs as Partenope, Carlo Vistoli as Arsace, Nicholas Tamagna as Armindo, Hadleigh Adams as Ormmonte, Daniela Mack as Rosmira

Julie Fuchs has joined the ranks of the great French divas (Dessay, Koch, d’Oustrac, Petibon, Devieilhe) who portray opera’s femmes fatales with profound depth and enormous wit. As a very shapely Partenope she has limitless opportunity to sing brilliantly, never losing her amusement that she must manage four suitors in breathtakingly beautiful roulades, adding energetic physical moves that convince us of the integrity of her frivolity.

Why and how stage director. Christopher Alden and his dramaturg Peter Littlefield, make Man Ray and the chic Parisian imagery of the 1920’s the link between our current sensibilities and those of early 18th century London is indeed a mystery. Nonetheless it offered a plenitude of possibilities to create the edgy schtick that kept us amused for the production’s 3 1/2 hour duration (even then 8 arias were cut, and a few orchestral sections were omitted).

Act II sports a toilet — always an edgy image — as the center of the action, perhaps an homage to Man Ray’s French contemporary Marcel Duchamp’s urinal. Or maybe it is just plain and simple toilet humor.

Alek Shrader (Emilio), Nicholas Tamagna (Armindo), Daniela Mack (Rosmira), Man Ray image, Julie Fuchs (Partenope), Carlo Vistoli (Arsace), Hadleigh Adams (Ormonte)

Alek Shrader (Emilio), Nicholas Tamagna (Armindo), Daniela Mack (Rosmira), Man Ray image, Julie Fuchs (Partenope), Carlo Vistoli (Arsace), Hadleigh Adams (Ormonte)

Alek Shrader (Emilio), Nicholas Tamagna (Armindo), Daniela Mack (Rosmira), Man Ray image, Julie Fuchs (Partenope), Carlo Vistoli (Arsace), Hadleigh Adams (Ormonte)

Alek Shrader (Emilio), Nicholas Tamagna (Armindo), Daniela Mack (Rosmira), Man Ray image, Julie Fuchs (Partenope), Carlo Vistoli (Arsace), Hadleigh Adams (Ormonte)

The ultra chic, ultra white decor was created by American designer Andrew Lieberman, onto which played an orgy of shadows, the handy work of American lighting designer Adam Silverman. The chic, high style costumes, by London designer Jon Morrell, were in primary colors and their derivatives that popped brightly against the pervasive whiteness of the stage.

The caricature of classical dance that defined Ormonte as a Baroque vision of some sort of exotic warrior, and other occasional quotes of the quintessential formality of French ballet, were the contribution of Irish choreographer Colm Seery.

The supertitles, created by British translator Amanda Holden, were approximations of what was being said in Italian on the stage, thereby enforcing an alacrity that enhanced this Christopher Alden comedy.

San Francisco Opera admits to a slight amplification of voices behind the WC door in Act II. There was, however, very clumsy amplification of voices apparent in Act I particularly, and other acts as well. Or will we be told to attribute this amplification phenomenon to sudden acoustic weirdnesses that occur in the War Memorial Opera House. Whatever, it was jarring and undermined the musical integrity of the performance.

War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, California. June 15, 2024. All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera

Erwartung at the San Francisco Symphony

In recent years the San Francisco Symphony has indulged itself with a staged event in June. This year, with a tightened budget, it was a brief evening made of Schönberg’s Erwartung together with Ravel’s Mother Goose Suite.

Composed in 1909 Erwartung (Expectation) is musical Modernism’s most complex and emotionally wrought work. The Schöneberg masterpiece was placed alongside what may be Modernism’s most simple piece, Ravel’s Ma mère l’Oye (1911) — a piano duet of no technical and little musical challenge for the children of a friend. The next year Ravel expanded it into a small ballet suite for orchestra.

It was a strange pairing indeed, envisioned either by San Francisco Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen or maybe by famed stage director Peter Sellars who created the minimal mise en scene for Erwartung.

The resulting performances were equally strange.

Ma mère l’Oye was entrusted to the Alonzo King Lines Ballet, San Francisco’s contemporary dance ensemble, with choreography by Alonzo King, the founder of the eponymous dance company. 12 dancers executed an unrelentingly complex, convulsive modern dance choreography that alternated full company moments with smaller ensembles of various numbers of dancers (see lead photo). The dances (a Spinning Wheel, Sleeping Beauty, Beauty of the Beast, Tom Thumb, Empress of the Pagodas, the Enchanted Garden) were very effective expositions of the impressive musculature of both the male and female dancers.

Meanwhile a reduced San Francisco Symphony was sequestered upstage on risers, creating the delicate beauty and sublime simplicity of the Ravel score, competing with the massive energy emanating from the dance platform.

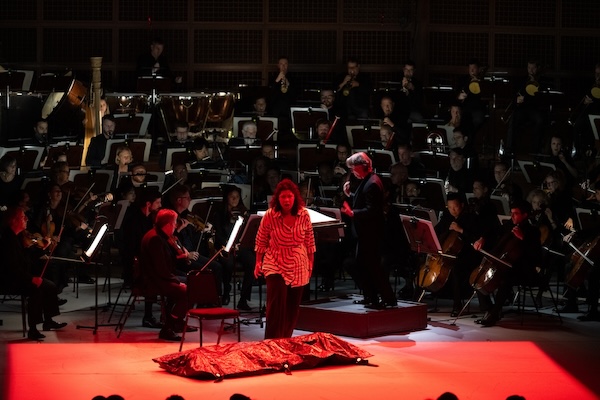

On the other hand Peter Sellars reduced Schönberg’s overwrought, meandering Freudian monodrama for soprano into quite basic, very understandable terms. In Sellar’s version a woman’s lover has been the victim of a sudden death “while in custody’ (projected on the large supertitle screen, that other times offered additional gratuitous political overtones as well). In the brief, silent introduction the body is consigned to her who then embarks on her process to reconcile herself to his death.

Mary Elizabeth Williams in Erwartung, Esa-Pekka Salonen conductor

Mary Elizabeth Williams in Erwartung, Esa-Pekka Salonen conductor

Now Schöneberg’s massive orchestra (quadruple winds, expanded percussion, full symphonic strings) spilled out onto the dance floor, leaving only a small, protruding square on which sat the soprano, Mary Elizabeth Williams, on one of the orchestra’s chairs. A body bag lay at her feet. She exposed her terrified grief in simple words, traversing her search for his love, the consummation of their love, the issue of their love, her fear that his world had betrayed him, that he had betrayed her, and that now she will be alone in the dawning light.

Dressed very simply in a white dress with vertebrae like black stripes Mme. Williams very directly exposed the immediate meaning of death. She possesses a dramatic soprano voice without the coloristic edges that soften the force of such a voice. She projects an honesty of emotion that is unique, specifically focused here in Schöneberg’s masterpiece on the terrifying reality of death.

From time to time a square of intense color would illuminate within the square of the small platform. Then at one point the confines of grief were burst open by a small rectangle of white light that suddenly extended up along the cellos of the orchestra where she moved, adding yet another perspective to the death of her lover — a brilliant Sellars coup de théâtre.

Meanwhile conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen focused the magnificent forces of the San Francisco Symphony onto realizing the astounding anti-repetitive thematic flows of Schöneberg’s fully atonal orchestration. A mass of sound was created that found a wonderful cacophonic harmony in this vivid contemplation of death.

Louise M. Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco, California. June 8, 2024. All photos copyright Kristen Loken, courtesy of San Francisco Symphony.

Innocence in San Francisco

Rarely has an opera performance enthralled audiences as has Kaija Saariaho’s Innocence just now at San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House.

We were entranced for its 105 minute duration, suffering the enduring traumas of a school massacre, recognizing our collective guilt, confessing our participation, and finding, finally, a certain redemption in our loss of innocence. [Lead photo is Rod Gilfry as the father, Ruxandra Donose as the waitress.]

Innocence is the last of Kaija Saariano’s six operas, completed two years before her death in July, 2023. The libretto was constructed in Finnish by Sofi Oksanen, a Finnish/Estonian novelist, and then made into this multilingual version by Saariaho’s son, D’Alesksi Barrière. Innocence premiered at France’s Aix Festival in 2021, a co-commission by San Francisco Opera with Helsinki (staged in 2022), Amsterdam and Covent Garden (staged in 2023), and the Metropolitan Opera (to be staged in 2025).

The commissioned production is by Australian stage director Simon Stone, well known on progressive European stages. Mr. Stone works in a kind of photo-journalism that establishes an immediacy and an urgency of musical/operatic reportage. He staged Innocence in a two story, open sided, modern building that is transformed as it slowly turns from a banquet room below the dining room of a restaurant complete with kitchen and bathrooms into a school with classrooms, restrooms, a broom closet, and a cafeteria. The continuing transformations of the structure’s Interiors and exteriors are somehow wrought by a huge team of backstage set dressers.

Ruxandra Donose as the Waitress (lower left), Vilma Jää as Markéta (standing in classroom), Lucy Shelton as the Teacher (seated upper left)

Ruxandra Donose as the Waitress (lower left), Vilma Jää as Markéta (standing in classroom), Lucy Shelton as the Teacher (seated upper left)

The storytelling is indeed complex, intermingling the traumatic, post massacre lives of the students and a teacher at an international school (one assumes in Finland) who had survived a massacre at the school ten years previously. The shooter, also a student, is soon to be set free (legally protected as a minor at the time of the crime). The shooter was and is loved by his mother, he had been given a gun by his father, he was worshipped by his younger brother. The shooter was aided by an abused friend and counseled by a priest.

Now, ten years later, at the opera’s inception the brother of the shooter is celebrating his wedding, his bride, an orphan, is a refugee from the Eastern bloc. By happenstance the waitress for the wedding banquet is the mother of one of the shooter’s victims. She, Tereza, is the catalyst for the disastrous wedding, and the destruction, emancipation, salvation and even some redemption for the myriad lives in which we immersed ourselves for the duration of the opera.

The Simon Stone production fit quite successfully onto the War Memorial stage. The casting was changed in important ways from the opera’s premiere in Aix. Most prominently in San Francisco was the role of the waitress Tereza, here performed by Bulgarian mezzo-soprano Ruxandra Donose. Mme. Donose possesses a great warmth of voice, as well she projected a humbled, beaten but proud persona, and a mother obsessively grieving for her murdered daughter — who was, and still is, the center of her life. This was the role that held the pivotal humanity of Innocence.

Left to right: Miles Mykkanen as Tuomas, Lilian Farahani as Stela, Kristinn Sigmundsson as the Priest, Claire de Sèvigné as Patricia, Rod Gilfry as Hynrik

Left to right: Miles Mykkanen as Tuomas, Lilian Farahani as Stela, Kristinn Sigmundsson as the Priest, Claire de Sèvigné as Patricia, Rod Gilfry as Hynrik

Another crucial cast change in San Francisco was Los Angeles bass baritone Rod Gilfry as the father, Hynrik, of the groom and the shooter. Mr. Gilfry has an unmistakable presence that exudes both strength and vulnerability, authority and insecurity. At age 65 he is in beautiful voice, and brought an important, vivid presence to the role of the terrified father. Canadian soprano Claire de Sèvigné was the mother of the shooter, Patricia, who sang in urgent, even strident tone her need to love her murderer son.

A further significant cast change was the role of the groom, Tuomas, in San Francisco taken by Michigan tenor Miles Mykkanen. Of beautiful, clear voice and vibrant presence he was the exuberant lover at his wedding, the insecure son arguing with his father, and finally the conflicted accomplice to the shooter who cowardly fled the scene of the shooting. In the end he was ruined, but freed from the innocence he had feigned.

Less successful was the casting of veteran San Francisco Opera bass Kristinn Sigmundsson as the priest. Insecure vocally he seemed lost on the stage, never actualizing the persona of a priest, much less the pious simplicity of a flawed country priest.

There were the splendid carry-overs from the original cast in Aix. Markéta, the ghost daughter of the waitress, was sung by Finnish soprano Vilma Jää in electronically modified, spectral tones. Dressed in black with platinum hair, and of towering figure, she, like her mother, was a pivotal voice in the humanity of Innocence with her mocking songs. The orphan bride Stela of the Aix cast was sung by Dutch soprano Lilian Farahani who projected a simplicity of voice and spirit, wanting only to escape her past, to find someone to love, and to find family. The teacher in the International School, from Aix as well, was skillfully enacted with a powerful presence by American soprano Lucy Shelton. She executed both guttural and sung tones in her two wrenching monologues.

In addition to Markéta there are five more international students with sung or sprechstimme roles in various languages. Among them was Student No. 3, known as Iris. Like Markéta, she was a pivotal voice in the humanity of the opera, and just like Markéta she was of towering stature with a platinum wig. Played by French actress Julie Hega, she spoke in very present, rich, warm French, carefully plotting with the shooter the murders of the students she hated. Angrily she detailed how she had been excluded from the triumph of the massacre, condemning the cowardice of the groom.

The relationships among the huge cast of singers and actors were exhaustively exposed, examined and portrayed in careful detail in this Simon Stone docudrama. It was re-created both in Amsterdam and San Francisco by British stage director Louise Bakker.

Where was composer Kaija Saariaho in all this, you may surely ask. French conductor Clément Mao-Takacs began the evening with an all too brief orchestral introduction where we could appreciate the magic of Mme. Saariaho’s score — splendid timbre based sounds in the French tradition, like Debussy, Ravel and Messiaen through a Boulez filter. Saariaho’s music is however very much its own voice, with sounds relating not on tonal relationships or serial order but in frequency synchronicity.

Mme. Saariaho must have known that her music could only float underneath and reinforce the horror of this contemporary story, so vividly exposed by stage director Simon Stone in his docudrama. Whereas the immediacy of Aix’s Grand Théâtre de Province gave much more presence to this magnificent orchestral score, the stage was far less involving than in San Francisco, and with far less sympathetic actors.

This problematic opera awaits a staging that balances the intensity of the story with the vibrancy of the score.

War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, California. June 7, 2024. All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera

Die Zauberflöte in San Francisco

It was a hot ticket in Berlin back in 2012, it has since played in L.A. (2013), Chicago (2021), Des Moines (2022), and around the world in many editions throughout the past decade. It’s Barrie Kosky’s The Magic Flute now on the stage of the War Memorial Opera House in San Francisco!

We all know Mozart’s Flute pretty well these days so we can easily welcome a riff on this all too familiar material. Actually the production was a collaboration for Berlin’s Komische Oper by the Australian born, Teutonic formed Barrie Kosky and Susanna Andrade of the British theater company named “1927” (the year of the film Jazzman, a monument of early filmic art that sits on the cusp of silence becoming sound in film).

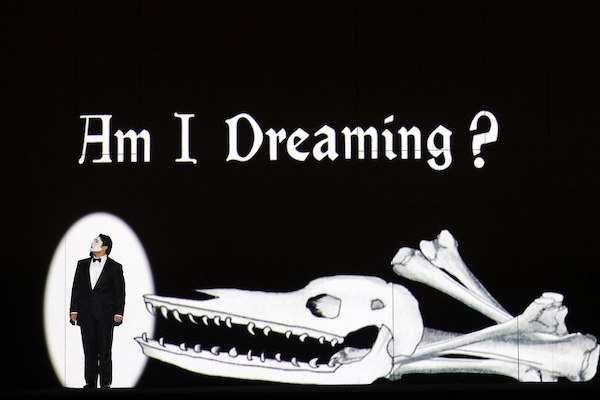

Though the production does not have the shock value of the huge caricatured Jew (hooked nose and evil grin) that Mr. Kosky (of Jewish descent) inflicted on a Bayreuth Meistersinger, nor the off-the-wall, weird sexual takes or outrageous nudity that often embellish Kosky productions, it does have the sheer audacity to butcher this holiest of all holy operas.

And to do so with unrelenting visual quotes from the silent film era with copious, added unrelenting animation. Never mind that it is charming — at least in intention. Suffice to say that the Queen of the Night is an animated spider, Papageno is Charlie Chaplin and the magic flute is a dragon fly. If nothing else the Kosky/Andrade production brilliantly rekindles the legendary Berlin/Hollywood film connection.

Tiny face of Anna Siminska as the Queen of the Night as a spider, Amitai Pati as Tamino

Tiny face of Anna Siminska as the Queen of the Night as a spider, Amitai Pati as Tamino

Audiences worldwide, and now San Francisco audiences too, react with delight, chuckles, ooh’s and ah’s, and sometimes even the laughs that silent films may elicit. Though however charmed audiences may be they are left bereft of the magnificence of Mozart’s magical singspiel.

The Kosky version eliminates all dialogue and much orchestral accompanied recitative, substituting mimed action with projected ye olde titles (descriptions or explanations) to the accompaniment of highly melodramatic moments from a few very highly amplified Mozart fortepiano pieces. The result is a disjointed musical flow, the opera no longer about words but instead about images, be they animated film cartoons or silent film quotations with simulated silent film piano sounds.

Mozartian magic could perhaps have been discovered in this imagistic storytelling had the singers been a larger component of the storytelling. The stage was simply a simulated, huge movie screen that sat immediately and elevated on the War Memorial stage. Most of the singing emanated from cut out openings high within the screen's structure. The voices often seemed far away, and sometimes superfluous to the orgy of projected images. Nonetheless here in San Francisco the famed arias and songs were all delivered with measured, studied artistry.

The singers had limited contact with San Francisco Opera music director Eun Sun Kim situated way down below. This served to isolate the pit from the stage, which often happens with this maestro when she either does not resonate with the singers or she loses contact. The un-staged overture was offered in stately, measured symphonic terms. The lack of clear plot flow however suppressed the symphonic terms that normally suffuse the second act.

On the other hand there was an astonishing coordination of the pit and voices with the flow of animation, un-nerving when it was not boring.

The music seldom took hold, in fact there were only two scenes where music enveloped the auditorium and these were the famed second act choruses, top-hatted singers in formal dress standing on the stage level of the imagined movie palace in front of its bright red curtain. San Francisco Opera’s maestra achieved real musical magic in these moments (though even here there was animated embellishment projected on a scrim, distancing us from the stage).

New Zealand tenor Amitai Pati gamely went through the paces of integrating himself into the animation, deftly dodging all illusionary obstacles thrown in his path. Mr. Pati is a polished performer, of refined voice. With the truly elegant phrasing of his arias he managed to elevate this Tamino to plausible candidacy for redemption. Austrian soprano Christina Gansch was an understated Pamina, vocally mismatched to the purer colors one wishes for this heroine’s voice and presence.

The star of the show was German baritone Lauri Vasar as Charlie Chaplin sans moustache aka Papageno. Mr. Vasar’s postures were pure Chaplin, vocally he was much more richly endowed than the usual Papageno. He was a warm, abstractly human silent film character (who incongruously sang beautifully) aided in no small way by the complete absence of the usual Schikaneder (the Magic Flute’s playwright) imposed schtick.

The face and voice of Polish soprano Anna Siminska was the Queen of the Night — the rest of Mme. Siminska was hidden behind the movie screen, her on screen character was a gigantic spider, her vocal presence was soft and pretty, hardly the impassioned, poisonous fury to match the measured authority of Sarastro, her enlightened counterpart. Sarastro was sung by Korean bass Kwangchul Youn, a role for which he is not suited. The Speaker was well projected by Korean bass Jongwon Han, the evil Monostatos, sung by Chinese tenor Zhengyi Bai, was lost in the fray of animation, as was the Papagena sung by Adler Fellow Arianna Rodriguez. On the other hand, the Queen of the Night's ladies-in-waiting were perfection itself, Soprano Olivia Smith, mezzo soprano Ashley Dixon and mezzo soprano Maire Therese Carmack made bright, lively sounds in impeccable ensemble. As well, the armored guards, tenor Thomas Kinch and bass-baritone James McCarthy made welcomed, forceful lively sounds as they descended in the basket of an animated balloon. The three spirits were well and very carefully sung by Niko Min, Solah Malik and Jacob A. Rainow who seemed appropriately terrorized by the maestra. This most recent edition of the Kosky/Andrade production was more colorful and more animated than the earlier version I saw in Los Angeles in 2013, obviously the victim of its continued travels worldwide. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, California. June 4, 2024. All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera

Daniel Catán’s Florencia en el Amazonas is having a moment. And just now at Silicon Valley’s Opera San Jose it was a quite wonderful moment — well cast, smart production — in its soaring, overwhelmingly passionate, surpassingly urgent musical dramas. Mexican composer Daniel Catán’s second opera La hija de Rappaccini (San Diego Opera,1994) brought him immediate U.S. operatic fame, inspiring Houston, Los Angeles and Seattle operas to commission Florencia en el Amazonas (Houston, 1996), followed by a Houston Opera commission for Salsipuedes o el amor, la guerra y unas anchoas [anchovies] (2004). Daniel Catán then composed Il Postino (a fictitious tale about Chilean poet Pablo Neruda) for baritone Placido Domingo (Los Angeles, 2010). Catán, by then a professor at Southern California’s [community] College of the Canyons, died at age 62, leaving his opera Meet John Doe unfinished. Of course, nothing crowns operatic success so much as a production at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Florencia en el Amazonas debuted there in November of last year [2023], though its New York City premiere had occurred in 2015 by the re-organized New York City Opera in a production from Nashville Opera. The opera has been seen in many American cities, but never, until now, in the Bay Area. In Florencia en el Amazonas, overpowering all its personal dramas — most notably the enduring love of fictitious opera diva Florencia Grimaldi for the long-disappeared butterfly hunter Christobál — is the Amazon river, always magically alive in its absolutely colossal orchestral presence. Catán relied on minimal orchestral means — only double winds, tuba, harp, piano, strings and expanded percussion to create this massive presence, wonderfully achieved in San Jose by conductor Joseph Marchese and Opera San Jose’s very able orchestra. In Catán’s opera the Amazon River is personified by Riolobo [rio=river, lobo=wolf, one of the many fanciful names in the opera] who has presence in the two worlds of the opera, a magically realistic world, and a world imbued by a mythical presence of magnificent natural forces. This role was well fulfilled by Maryland-born baritone Ricardo José Rivera, effecting a big presence for Riolobo in finely honed tones. Daniel Catàn’s librettist was Mexican screen writer Marcela Fuentes-Berain, a student of famed Columbian novelist Gabriel Garcia Márquez, who originally was to provide a libretto for Catàn. Finally, the opera’s story is in fact very loosely based on his El amor en los tiempos del cólera, asking if love can be eternal. In the opera the riverboat El Dorado departs Leticia, Colombia, to go downriver to Manaus (about 700 miles), The opera enacts the very fraught situations of a few of its passengers and two of its crew, the boat’s captain embodied by fine bass-baritone, resident Opera San Jose artist Vartan Gabrielian, and his son Arcadio, sung by Merixcan tenor César Delgado. Like a Rossini opera, Florencia en el Amazonas is a succession of arias, duets, trios, quartets, each of its two acts capped by a finale (quintet, sextet or septet) with chorus. Each piece is a moment of high crisis. Florencia, sung by soprano Elizabeth Caballero (see lead photo), is searching to find herself and her lost, unseen lover, Christobál. The journalist Rosalba, sung by soubrette soprano Aléxa Anderson, wishes to connect with her idol Florencia (who will sing when the boat reaches Manaus) but Rosalba’s journey becomes complicated when she and Arcadio fall in love, though they both disdain love. As well Arcadio is imprisoned by both the river and by his father, the boat’s captain.

Wretched indeed were Alvaro, sung by baritone Efrain Solís, a former San Francisco Opera Adler, and his wife Paula, beautifully sung by mezzo-soprano Guadalupe Paz as a mature couple searching to find the love that had once bound them together. And the ship’s captain whose relationship with his river, the Amazon was decidedly one sided when the boat ran aground at the abrupt ending of Act I. As performed in San Jose Catán’s opera is a gem, never succumbing to the mere lush richness of its sound, always finding its melodramas of great immediacy, its resolutions always elusive and its emotional challenges rendered terribly comprehensible — and very pleasurable to endure. The music, the river, life itself is indeed beautiful in the opera’s cinematic symphonic richness. And, yes, when they arrive finally at Manaus where the diva is to perform, they cannot disembark because of an outbreak of cholera. But this is its moment of transcendence. No longer of this world Florencia Grimaldi becomes the rare butterfly, the emerald muse that her lover Christobál had once sought. Love is eternal.

This new production was staged by Puerto Rican director Crystal Manich, known to Opera San Jose audiences for her recent staging of West Side Story. The set was basically the bridge of a riverboat and a frame for its paddles, plus diverse drops of jungle foliage that descended from time to time. Transcendence was achieved by a blank, saturated blue surround. The set designer was Liliana Duque-Piñeiro known to Bay Area audiences for productions at West Edge Opera. The lighting of the stage and actors by designer Tlaloc López Watermann was very effective. The colorful costumes were designed by Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s Ulises Alcala. The 16 singers of the Opera San Jose chorus seemed just the right number to populate the stage of San Jose’s repurposed historic movie palace, the California Theatre. California Theatre, San Jose, California, April 20, 2024. All photos copyright David Allen, courtesy of Opera San Jose.

Two recent one-acts cleverly combined by stage director Brian Staufenbiel into one grand, operatic sporting event. San Francisco’s alternative opera company, Opera Parallele pulled off a slam dunk show. It all took place in Houston’s nearly 70,000 seat Astrodome inserted into SF Jazz’s 700 seat Miner Auditorium. It was all hosted by the famously arrogant Howard Cosell [a sportscaster in the 1960’s and 70’s] impersonated with great affection by Opera Parallele’s Mark Hernandez. Somehow all necessary magnitude (gigantic) was achieved to showcase the brutal competition among six male finches as well as the 1973 Houston Battle of the Sexes — US Open champion (retired) Bobby Riggs pitted against Grand Slam champion Billie Jean King. Vinkensport or The Finch Opera, the “Birds” part of the title, re-imagined the ancient Flemish rite that determines which male finch can sing the most songs in one hour. The opera limits the competition to six finches (named Hans Sachs, Prince Gabriel III of Belgium, etc.), though they remained unseen except for a dead one (Farinelli). Nor, ironically, were they heard — though there was a plentitude of birdlike sounds always rising from the pit. The Vinkensport librettist Royce Vavrek has been dubbed the Metastasio [a famously prolific Baroque librettist] of Brooklyn, though he is more appropriately aligned with the prolific French grand opera librettist Eugène Scribe, famed because he could turn any story or situation into a succession of arias and choruses, plus adding the sine non qua of grand opera — spectacle! Spectacle was no problem (Astrodome battles). Fortunately the bird songs were kept in the pit and we had to contend only with the sad fates of the birds’ trainers.

It was no longer comedy as the trainer of the bird named Holy St. Francis’s imagined (through the eye of her bird) her husband “stuffing the turkey” (fucking — an inelegant image in an otherwise elegant staging) on the kitchen table, Farinelli’s trainer imagined a solemn funeral for her dead bird, Elton John’s trainer contended with alcoholism, etc. Finally the trainer of the bird named Atticus Finch (the lawyer in the novel “To Kill a Mockingbird” who defended a black man charged with rape) was left alone on the stage. Sung by fine baritone Daniel Cilli, he movingly admitted that he existed only though his bird. [I surmised this content as I was seated behind a bank of speakers that blocked the supertitles — the program synopsis was far from detailed]. The Vinkensport score is by David T. Little. The work was commissioned by Bard College, premiering in 2010. Little, once a drummer, is a composer who boasts several successful operas (JFK, Soldier Songs, and Dog Days). He is a member of the group Newspeak, exploring the boundaries of rock and classical music, explaining, maybe, why this opera found itself on the SF Jazz stage. In this chamber version of the original score there were four string voices (SSTB), plus flute and clarinet, myriad percussion (two players) and piano, the ensemble creating an amusing, new music maelstrom carefully presided upon by Opera Parallele’s music director Nicole Paiement. Vinkensport flowed directly into Balls, the stage easily transformed from a line-up of finch competitors into a tennis court, the projections covering/hiding the acoustically engineered walls of this distinctly unattractive auditorium changing from a leafy glen into the stadium seats of the Astrodome. The pit added a few brass players and a saxophone to create the big band sounds that took us to another time, specifically 1973 and the hugely hyped match between la King and Mr. Riggs — the purse was $100,000 winner-take-all, that’s $700,000 in today’s dollars! The stakes were high indeed.

Balls’ diva was enacted by mezzo soprano Nikola Printz in a tour de force performance. They (nonbinary pronoun) exhibited all the needed balls to whip (or so it seemed) tenor Nathan Granner as the 55 year-old Bobby Riggs, in an equal tour de force performance — a true battle of champions played before our very eyes — Nikola Printz exhibited a mighty backhand slice, never faltering in a full voiced accompanying commentary, Mr. Granner excelled at tennis’ drop shot, while never dropping a word — of which this renowned tennis hustler had many. The Balls librettist is Gail Collins, the first woman to serve as the NY Times editorial page editor, now the liberal voice on the NY Times podcast “The Conversation” and author of “America’s Women: Four Hundred Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates and Heroines.” So why not an opera libretto celebrating one of the great icons of twentieth century American feminism. Like "The Conversation" podcast the Balls libretto bounces gracefully from subject to subject, person to person, viewpoint to viewpoint, place to place succinctly encapsulating the Billie Jean King of 1973. It was a year in which she was in full competitive form, in a stable (or so it seems) marriage with Larry King, and in a lesbian relationship with her secretary/hairdresser Marilyn Barnett, operatically painted as a seductive jazz singer, here sung by fine jazz singer Tiffany Austin. (see lead photo) Not to forget that King was the winner-take-all of this lucrative battle. Note as well that King’s arch tennis rival Margaret Court had been defeated by Bobby Riggs four months earlier in a match also known as a battle of the sexes. Billie Jean King’s accomplishments were myriad. Advancing the emerging movement of gender equality she founded the Women’s Tennis Association and the Women’s Sports Foundation. She persuaded Virginia Slim cigarettes to sponsor women’s tennis in the 1970’s. All this history and accomplishment was cleverly woven into the Gail Collins libretto. This was the Bille Jean King to be celebrated, and that the Brian Staufenbiel production did with consummate pizazz. Yes, of course, Susan B. Anthony, sung with fine musicality by Shawnee Sulker, found her way onto the stage, creating a procession thrusting forward under a projection of the famed Delacroix painting (1830) of bare-breasted ‘lady Liberty Leading the People’ to topple French king Charles X (Susan B. was 10 years-old at the time). Composer Laura Karpman’s Balls had its premiere at LA’s The Industry in 2017, its gestation supported by a 2015 Opera America grant. Composer Karpman always titled her opera Balls, not to be confused with the movie entitled The Battle of the Sexes (same story though in cinematic terms) that came out in 2017 as well. Mme. Karpman is based in Los Angeles where she has extensive Oscar, Emmy and Grammy nominations and awards, as well as orchestral and opera commissions from the L.A. Phil’s Hollywood Bowl and Opera Theatre of St. Louis. The Balls score is rich indeed, easily traversing the many styles needed to illuminate this triumphal moment of feminist history. The evening was monumental, Opera Parallele in all its alternative glory. The operas were rich with meaning and rich in sound, flawlessly produced and beautifully performed by a large ensemble of fine singers, and an excellent ensemble of instrumentalists. Vinkensport, or The Finch Opera Holy St. Francis’ Trainer - Jamie Chamberlain; Atticus Finch’s Trainer - Daniel Cilli; Hans Sachs’ Trainer - Nathan Granner; Butler/Referee - Mark Hernandez; Farinelli’s Trainer - Chelsea Hollow; Sir Elton John’s Trainer - Shawnette Sulker; Prince Gabriel III of Belgium’s Trainer - Chung-Wai Soong. Balls Marilyn, Jazz Singer - Tiffany Austin; Larry King - Daniel Cilli; Bobby Riggs - Nathan Granner; Howard Cosell - Mark Hernandez; Rosie Casals - Gabriela Linares; Billie Jean King - Nikola Printz; Susan B. Anthony - Shawnette Sulker; Vocal Quartet Soprano - Jamie Chamberlain; Vocal Quartet Mezzo-Soprano - Nina Jones; Vocal Quartet Tenor - Chad Somers; Vocal Quartet Baritone - Chung-Wai Soong. Conductor - Nicole Paiement; Stage and Creative Director - Brian Staufenbiel; Projection Designer - David Murakami; Costume/Hair/Makeup Designer - Y. Sharon Peng; Lighting Designer - Mextly Couzin. Miner Auditorium of SF Jazz, April 6, 2024 All photos copyright Kristen Loken, courtesy of Opera Parallele

Florencia en el Amazonas at Opera San Jose

Standing Efrain Solis as Alvaro, Guadalupe Pas as Paula, seated Aléxa Anderson as Rosalba, César Delgado as Arcadio

Standing Efrain Solis as Alvaro, Guadalupe Pas as Paula, seated Aléxa Anderson as Rosalba, César Delgado as Arcadio

Elizabeth Caballero as Florencia in the final moments of the opera, Ricardo José Rivera as Riolobo (very dimly lighted)

Elizabeth Caballero as Florencia in the final moments of the opera, Ricardo José Rivera as Riolobo (very dimly lighted)

"Birds and Balls" at San Francisco's Opera Parallele

The trainers of the six competing finches, Left to right: Holy St. Francis, Farinelli, Sir Elton John (standing forward), Hans Sach, Prince Gabriel III of Belgium, Atticus Finch

The trainers of the six competing finches, Left to right: Holy St. Francis, Farinelli, Sir Elton John (standing forward), Hans Sach, Prince Gabriel III of Belgium, Atticus Finch

Billie Jean King in triumph, the defected Bobby Riggs in blue shirt, Houston Astrodom projection in background.

Billie Jean King in triumph, the defected Bobby Riggs in blue shirt, Houston Astrodom projection in background.